Woodrow Wilson’s Folly gave rise to more than the 1,000 year flood of Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism and their state orchestrated campaigns of mass murder.

It also opened the door to massive, cheap war finance. And that baleful innovation has sustained the Empire long after Hitler and Stalin met their maker and the case for the Indispensable Nation had become ragged and threadbare.

In the context of American democracy – special interest dominated as it is – the greatest deterrents to imperial adventurism and war are the draft and taxes. Both bring home to the middle class voting public the cost of war in blood and treasure (theirs), and force politicians to justify the same in terms of tangible and compelling benefits to homeland security.

We leave the draft for another day, but do note that when the draft expired in 1970 what ended was not imperial wars – only middle class protests against them.

In fact, the Empire has learned to make do, happily, with essentially mercenary forces recruited from the left behind precincts of the rust belt and southeast and the opportunity deprived neighborhoods of urban America.

But even mercenaries, and the upkeep, infrastructure and weaponry of the expeditionary forces which they comprise, cost lots of money. And that would ordinarily be a giant problem for the Imperial City because the folks in the hinterlands have a deep and abiding allergy to high taxes.

As we explain below, however, Woodrow Wilson solved that problem, too, by drafting the printing press of the newly minted Federal Reserve for war finance duty.

So doing, he opened the Pandora’s box of Federal debt monetization by permitting the Fed to own government debt – a step strictly forbidden by the stringent 1913 enabling statute drafted by the legendary maestro of sound money, Congressman Carter Glass.

Needless to say, as a political matter printing money is a lot easier than taxing the people. And that’s especially true when the spending in question involves the machinations of Empire in distant lands spread about the planet at a time when citizens on the home front feel abused and over-taxed already.

To be sure, we happen to believe that the spending and tax burden on GDP could be far smaller than it is in the US today under a regime of true federalism, honest free markets and minimalist government intervention in social and economic life.

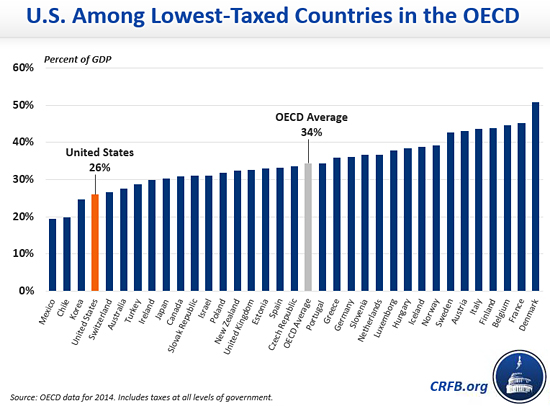

Still, compared to the rest of the developed world, the total US tax burden (Federal, state and local) is just 26% of GDP. That compares to an OECD average of 34% and upwards of 50% in many of the more "advanced" venues of European socialism (e.g. Belgium, France and Denmark).

Nevertheless, the voters abhor taxes – and the modern anti-tax GOP does not miss a beat in prosecuting the case for even lower extractions.

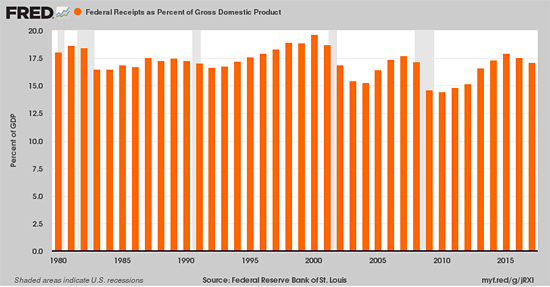

The upcoming FY 2019 is a quintessential expression of that sentiment. Federal taxes will clock in at just 16.5% of GDP – virtually the lowest rate in the last 40 years outside of deep recessions.

At the same time, the full cost of Empire will nearly tag a record $1 trillion including $700 billion for defense, $200 billion for Veterans – as well as security assistance and international ($64 billion) and debt service on past wars ($36 billion).

Needless to say, the square peg of Empire abroad and the Welfare State at home could never be pounded through the round hole of low taxes – that is, not without the lubricant of massive monetization of the public debt.

Had Wilson not opened the door to printing press finance of the War Machine, the "draft-effect" would have throttled the Empire long ago.

That’s is to say, the crowding out by Uncle Sam and the resulting soaring bond yields would have mobilized the natural antiwar constituencies. We are referring especially to the nation’s 15 million small businesses and 75 million homeowners, who would have felt the painful sting of high interest rates in their pocketbooks.

For that reason we now turn to Wilson’s second abomination after Versailles and all its progeny. We refer to the transformation of the Federal Reserve from a passive “banker’s bank” to an interventionist central bank knee-deep in Wall Street, government finance and macroeconomic management.

This, too, was a crucial historical hinge point because Carter Glass’ 1913 act forbid the new Reserve banks from owning even a single dollar’s worth of government debt.

To the contrary, they were empowered only to passively discount for cash good commercial credits and receivables (called "real bills") brought to the Fed’s rediscount windows by member banks.

Accordingly, the legislative authors contemplated no open market interventions in government bond markets; no interactions with Wall Street dealers and bond market speculators; and provided no remit at all with respect to GDP growth, jobs, inflation, housing or all the rest of modern day monetary central planning targets.

In fact, Carter Glass’ “banker’s bank” didn’t care whether the growth rate was positive 4%, negative 4% or anything in-between.

Its modest job was to channel liquidity into the banking system in response to the ebb and flow of commerce and production based on the very collateral ("real bills") generated by that economic activity on the free market.

Accordingly, jobs, growth and prosperity were to remain the unplanned outcome of millions of producers, consumers, investors, savers, entrepreneurs and speculators operating on the free market, not the business of the state.

But Wilson’s war increased the national debt by 27X.

That’s right. As of 1914 the public debt was just $1 billion or $11 per capita and amounted to less than 2% of GDP – a level which had been maintained since the Battle of Gettysburg.

But by the end of 1919, the public debt had mushroomed to $27 billion, including upwards of $10 billion re-loaned to the allies to enable them to continue the war.

There is not a snowball’s chance in the hot place, of course, that this massive and virtually overnight eruption of Federal borrowing could have been financed out of domestic savings in the private market.

So the Fed’s charter was fatefully changed owing to the exigencies of war to permit it to own government debt and to discount private loans collateralized by Treasury paper.

In due course, Wilson’s famous and massive Liberty Bond drives became a glorified Ponzi scheme.

Patriotic Americans borrowed money from their local banks to buy war bonds and then pledged them as security. These hometown banks, in turn, then re-pledged their customer’s collateral in order to borrow a like amount of funds from their regional Federal Reserve Bank.

Finally, the Reserve banks created the billions they loaned to their member hometown banks out of thin air, thereby pegging interest rates ultra-low for the duration of the war.

Thus, when Wilson was done preparing the world for the 1,000 year flood of totalitarianism, America also had an interventionist central bank.

And it was one now schooled in the art of interest rate pegging and rampant expansion of fiat credit anchored in government debt, not the self-regulating "real bills" (pledges of receivables and fished goods inventory) of commerce and trade.

Thus was borne in 1917-1919 both the rationale for Empire and the state instrumentalities needed finance it easily and on the cheap. That is, massive Warfare State spending without the inconvenience of high taxes on the people or the crowding out of business investment by high interest rates on the private market for savings.

By prolonging the war and massively increasing the level of debt and money printing on all sides, Wilson’s folly also prevented a proper postwar resumption of the classical gold standard at the prewar parities.

And that was of epic consequence, too.

That’s because this failure of "resumption" and the restoration of prewar currency parities against their historic weight in gold, in turn, paved the way for the breakdown of monetary order and world trade during the late 1920s, culminating in the British default on the gold standard in 1931.

As we chronicled in The Great Deformation, this monetary breakdown turned a standard postwar economic cleansing into the Great Depression, and a decade of protectionism, beggar-thy-neighbor currency manipulation and ultimately rearmament and statist dirigisme throughout much of the world.

In essence, the English and French governments had raised billions from their citizens on the solemn promise that it would be repaid at the prewar parities; that the war bonds were money good in gold.

But the combatant governments had printed too much fiat currency and generated roaring inflation during the war, including a 200% increase in the price level in England, 300% in France and far more in Germany.

Moreover, through domestic regimentation, heavy taxation and unfathomable combat destruction of economic assets, the belligerent governments had drastically impaired their own private economies.

As a result, the restoration of sound money and healthy capitalist economies would have required years of austerity and reinvestment.

But under foolish leadership of Winston Churchill in 1925, England attempted to re-peg the pound sterling to gold at the old prewar parity (which had been in place since 1719).

Yet the British government had no political will or capacity to reduce bloated wartime wages, costs and prices in a commensurate manner, or to live with the austerity and shrunken living standards that honest liquidation of its war debts required.

At the same time, France did the opposite. It ended up betraying its war time lenders, and re-pegged the Franc two years later at a drastically depreciated level.

This resulted in a spurt of beggar-thy-neighbor prosperity and the accumulation of pound sterling claims that would eventually blow-up the London money market and the sterling based “gold exchange standard” that the Bank of England and British Treasury had peddled as a poor man’s way back on gold.

Yet under this “gold lite” contraption, France, Holland, Sweden and other surplus countries had accumulated huge amounts of sterling liabilities in lieu of settling their accounts in gold bullion – that is, they loaned billions to the British.

They did this on the promise and the confidence that the pound sterling would remain at $4.87 per dollar come hell or high water – just as it had for 200 years of peacetime before.

But British politicians betrayed their promises and their central bank creditors in September 1931 by suspending redemption and floating the pound. That shattered the parities, generated massive losses among Bank of England creditors and caused the decade-long struggle for resumption of an honest gold standard to fail.

Depressionary contraction of world trade, capital flows and capitalist enterprise inherently followed.

And on the American side of the Atlantic, in turn, another part of Wilson’s due bill was called in.

By turning America overnight into the granary, arsenal and banker of the Entente, the US economy had been distorted, bloated and deformed into a giant, but unstable and unsustainable global exporter and creditor.

During the war years, for example, US exports increased by 4X and GDP soared from $40 billion to $90 billion. Incomes and land prices soared in the farm belt, and steel, chemical, machinery, munitions and ship construction boomed like never before – in substantial part because Uncle Sam essentially provided vendor finance to the bankrupt allies in desperate need of both military and civilian goods.

Under classic rules, there should have been a nasty correction after the war – as the world got back to honest money and sound finance. But it didn’t happen because the newly unleashed Fed fueled an incredible boom on Wall Street and a massive junk bond market in foreign loans.

In today economic scale, the latter amounted to upwards of $2 trillion and, in effect, kept the war boom in exports and capital spending going right up until 1929. Accordingly, the great collapse of 1929-1932 was not a mysterious failure of capitalism; it was the delayed liquidation of Wilson’s war boom.

After the crash, exports and capital spending plunged by 80% when the foreign junk bond binge ended in the face of massive defaults abroad; and that, in turn, led to a traumatic liquidation of industrial inventories and a collapse of credit fueled purchases of consumer durables like refrigerators and autos.

The latter, for example, dropped from 5 million to 1.5 million units per year after 1929.

In short, the Great Depression was a unique historical event owing to the vast financial deformations of the Great War – deformations which were drastically exaggerated by its prolongation from Wilson’s intervention and the massive credit expansion unleashed by the Fed and Bank of England during and after the war.

Stated differently, the trauma of the 1930s was not the result of the inherent flaws or purported cyclical instabilities of free market capitalism; it was, instead, the delayed legacy of the financial carnage of the Great War and the failed 1920s efforts to restore the liberal order of sound money, open trade and unimpeded money and capital flows.

But this trauma was thoroughly misunderstood, and therefore gave rise to the curse of Keynesian economics in most parts of the world.

That took the form of war mobilization and rearmament in Nazi Germany, labor welfarism in England and France and New Deal public works boongoogles in the US. And everywhere it did unleash the politicians to meddle in virtually all aspects of economic life, culminating in the statist and crony capitalist leviathans that have emerged in this century.

Indeed, Thomas Woodrow Wilson is the father of most of the last century’s ills. His grand crusade gave the world the curse of Stalin and Hitler, which, in turn, fostered the fallacy of the Indispensable Nation and gave rise to Imperial Washington and its destructive projects of global Empire.

Worst of all, his perversion of Carter Glass’ "bankers’ bank" made it possible to finance the Empire on the cheap and to nullify the natural antiwar constituency of middle class taxpayers.

That was Woodrow Wilson’s worst sin of all.

And at length and after all these decades it has led straight to the crisis of Bubble Finance and Empire that loom dead ahead, as we will amplify in Part 4.

David Stockman was a two-term Congressman from Michigan. He was also the Director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan. After leaving the White House, Stockman had a 20-year career on Wall Street. He’s the author of three books, The Triumph of Politics: Why the Reagan Revolution Failed, The Great Deformation: The Corruption of Capitalism in America and TRUMPED! A Nation on the Brink of Ruin… And How to Bring It Back. He also is founder of David Stockman’s Contra Corner and David Stockman’s Bubble Finance Trader.