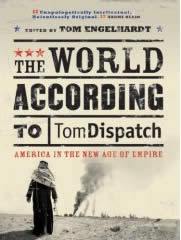

[Note for TomDispatch readers:We live in a media world with a remarkably short memory, which means that stories with a past go missing in action all the time. Witness the one that follows. To the extent my aging brain is able, TomDispatch tries to keep the past in mind and, when it comes to the recent past, not to forget the remarkable record of the Bush administration in its various wars. This Web site aims to rescue at least a few of the missing stories of our age, before they slip through the cracks forever. The new book, The World According to TomDispatch: America in the New Age of Empire, is, I think, a striking record of this site’s recovery efforts over the last years. I hope those of you who haven’t yet gotten yourselves a copy will consider doing so. Think of it as a gesture of moral support for a site in the memory repo business. Tom]

It was a tribal affair. Against a picture-perfect sunset, before a beige-colored cross and an altar made of the very Texas limestone that was also used to build her family’s “ranch,” veil-less in an Oscar de la Renta gown, the 26-year-old bride said her vows. More than 200 members of her extended family and friends were on hand, as well as the 14 women in her “house party,” who were dressed “in seven different styles of knee-length dresses in seven different colors that match[ed] the palette of … wildflowers – blues, greens, lavenders, and pinky reds.” Afterward, in a white tent set in a grove of trees and illuminated by strings of lights, the father of the bride, George W. Bush, danced with his daughter to the strains of “You Are So Beautiful.” The media was kept at arm’s length and the vows were private, but undoubtedly they included the phrase “till death do us part.”

That was early May of this year. Less than two months later, halfway across the world, another tribal affair was underway. The age of the bride involved is unknown to us, as is her name. No reporters were clamoring to get to her section of the mountainous backcountry of Afghanistan near the Pakistani border. We know almost nothing about her circumstances, except that she was on her way to a nearby village, evidently early in the morning, among a party 70-90 strong, mostly women, “escorting the bride to meet her groom as local tradition dictates.”

It was then that the American plane (or planes) arrived, ensuring that she would never say her vows. “They stopped in a narrow location for rest,” said one witness about her house party, according to the BBC. “The plane came and bombed the area.” The district governor, Haji Amishah Gul, told the British Times, “So far there are 27 people, including women and children, who have been buried. Another 10 have been wounded. The attack happened at 6:30 a.m. Just two of the dead are men, the rest are women and children. The bride is among the dead.”

U.S. military spokespeople flatly denied the story. They claimed that Taliban insurgents had been “clearly identified” among the group. “[T]his may just be normal, typical militant propaganda,” said 1st Lieutenant Nathan Perry. Despite accounts of the wounded, including women and children, being brought to a local hospital, Capt. Christian Patterson, coalition media officer, insisted: “It was not a wedding party, there were no women or children present. We have no reports of civilian casualties.” The members of an Afghan inquiry, appointed by President Hamid Karzai, later found that, in all, 47 civilians had died, including 39 women and children, and nine others were wounded.

Here’s another American take on what happened: “The U.S. military has denied allegations that its forces … killed dozens of people celebrating a marriage. … ‘We took hostile fire and we returned fire,’ said Brigadier General Mark Kimmitt, deputy director of operations. … He said there were no indications that the victims of the attack were part of a wedding party.”

Oh, my mistake. Kimmitt was denying that a different wedding party had been obliterated – in the Western Iraqi desert, near the Syrian border, in May 2004. In that case, the wedding feast was long over. The celebrations had ended and the guests were evidently in bed when the U.S. jets arrived. More than 40 people died, including children, women, musicians, and a well-known Iraqi wedding singer hired for the event. According to Rory McCarthy of the British Guardian, who interviewed some of the hospitalized survivors, 27 members of one extended family died when the jets arrived.

In response to reports on that 2004 slaughter, Maj. Gen. James Mattis, commander of the 1st Marine Division, asked the following question: “How many people go to the middle of the desert … to hold a wedding 80 miles from the nearest civilization?” And, in an e-mail responding to questions from a New York Times reporter, Gen. Kimmitt later offered what was, by U.S. military standards, little short of an admission: “Could there have been a celebration of some type going on? … Certainly. Bad guys have celebrations. Could this have been a meeting among the foreign fighters and smugglers? That is a possibility. Could it have involved entertainment? Sure. However, a wedding party in a remote section of the desert along one of the rat lines, held in the early morning hours, strains credulity.”

The comments of Mattis and Kimmitt deserve, of course, to go directly into the annals of American military quotes, right next to that Vietnam-era classic: “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.”

But back to the subject of collateral ceremonial damage in Afghanistan. Consider this passage from a news report headlined, “No U.S. Apology Over Wedding Bombing,” in the Guardian:

“Afghans claim the wedding guests, who were celebrating near Deh Rawud village, in the mountainous province of Oruzgan, north of Kandahar, had been firing into the air – a Pashtun wedding tradition – when American planes struck. But a U.S. spokesman claimed yesterday that the shooting was ‘not consistent’ with a wedding, saying that the planes had come under attack. ‘Normally when you think of celebratory fire … it’s random, it’s sprayed, it’s not directed at a specific target,’ said Colonel Roger King at the U.S. airbase at Bagram. ‘In this instance, the people on board the aircraft felt that the weapons were tracking them and were [trying] to engage them.'”

That was indeed Afghanistan – not in July 2006, however, but four Julys earlier, when at least 30 people in a wedding party were wiped out, most of them, again, reportedly women and children. Here’s how Abdullah Abdullah, the Afghan foreign minister at the time, described that American air attack. It killed, he said, “a whole family of 25 people. No single person was left alive. This is the extent of the damage.”

Oh, and let’s not forget the ur-incident in wedding party destruction in Bush’s wars. In late December 2001, a B-52 and two B-1B bombers, using precision-guided weapons, essentially wiped out a village in Eastern Afghanistan (and then, in a second strike, took out Afghans digging in the rubble). At the time, it was claimed that Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders had been killed “in their sleep.” It was also claimed that surface-to-air missiles had been fired at the American planes. A spokesman for the U.S. Central Command issued a congratulatory statement after the attack occurred with this passage: “Follow-on reporting indicates that there was no collateral damage.”

Oh, and let’s not forget the ur-incident in wedding party destruction in Bush’s wars. In late December 2001, a B-52 and two B-1B bombers, using precision-guided weapons, essentially wiped out a village in Eastern Afghanistan (and then, in a second strike, took out Afghans digging in the rubble). At the time, it was claimed that Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders had been killed “in their sleep.” It was also claimed that surface-to-air missiles had been fired at the American planes. A spokesman for the U.S. Central Command issued a congratulatory statement after the attack occurred with this passage: “Follow-on reporting indicates that there was no collateral damage.”

Except, of course, as Guardian correspondent Rory Carroll, then in Afghanistan, put it, “bloodied children’s shoes and skirts, bloodied school books, the scalp of a woman with braided gray hair, butter toffees in red wrappers, wedding decorations. The charred meat sticking to rubble in black lumps could have been Osama bin Laden’s henchmen but survivors said it was the remains of farmers, their wives and children, and wedding guests.”

In fact, according to Time magazine’s Tim McGirk, out of 112 Afghans in the wedding party, only two women survived. In this case, it seems that the Americans were fed disinformation by an Afghan official out to settle scores and acted on it.

That makes four wedding parties blown away by U.S. air power in Iraq and Afghanistan since the end of 2001. And there was probably at least one more. Back in May 2002, it was claimed that U.S. helicopters wiped out a wedding party in the eastern Afghan province of Khost, killing 10 and wounding many more. An Agence France Presse report at the time concluded: “A wedding was in progress in the village when people fired into the air in traditional celebration and U.S. helicopters flying over the area could have mistaken it for hostile fire. An aircraft later bombed the area for several hours.” On this event, however, the documentation is far poorer.

All these “incidents” have some obvious features in common: the almost immediate claims by the U.S. military, for instance, that those who have been hit were adversaries, not wedding parties; the ultimate dismissal of the killings as the usual “collateral damage” in wartime; and, above all, the striking fact that, for none of these slaughters of celebrating locals, did the U.S. ever offer a genuine apology.

The mainstream media tends to pick up such stories as he said/she said affairs. Of course, “she” never actually “says” anything, being dead. But you get the idea. As with the most recent Afghan wedding-party slaughter, such pieces – generally wire service stories – are to be found deep inside American newspapers where only the news jockeys are reading. In fact, your basic wedding party wipeout report is almost certain to share at least some space in the story with a mini-round-up of other kinds of recent death and mayhem in the region in question. The language in which such stories are written is generally humdrum and, in the military mode, death is sanitized (except in rare instances like Carroll’s fine reports for the Guardian).

We Americans have only had one experience of death delivered from the air since World War II – the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. As no one is likely to forget, they shocked us to our core. And you know how those deaths were covered, right down to the special pages filled with bios of civilians who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and the repeated invocations of the barbarism of al-Qaeda’s killers (and barbarism it truly was).

These wedding parties, however, get no such treatment. Initially, they are automatically assumed to be malevolent – until the reports begin to filter in from the hospitals, the ruined villages, and the graveyards, and, by then, it’s usually too late for much press attention. When that does happen, their deaths are chalked up to an “errant bomb,” or that celebratory gunfire, or no explanation is even offered.

Nothing barbaric lurks here, even though we can be sure that these civilians were hardly less surprised by the arrival of the attacking planes than were the victims of 9/11. For their deaths, no word portraits are ever painted. No one in our world thinks to memorialize them, nor is there any cumulative record of their deaths. Whole extended families have been wiped out, while the dead and wounded run into the hundreds, and yet who remembers?

Here’s the truth of it: In Bush’s wars, the wedding singer dies, the bride does not get a chance to run away, and the event might be relabeled my big, fat, collateral damage wedding.

In the process, we have become a nation of wedding crashers, the uninvited guests who arrived under false pretenses, tore up the place, offered nary an apology, and refused to go home. It’s a remarkable record, really, and catches the nature of the Bush administration’s air war not on, but of and for terror in a particularly raw way. And yet, in this country, when the latest wedding party went down, no reporter seems even to have recalled our past history of wedding-party obliteration. So it goes.

Copyright 2008 Tom Engelhardt