“A ministry of risk goes unerringly to the side of the victims, to those threatened or destroyed by greed, prejudice, and war. From the side of those victims, it teaches two simple, indispensable lessons: (1) that we all belong in the ditch, or in the breach, with the victims; and (2) that until we go to the ditch or into the breach, victimizing will not cease.” ~ Philip Berrigan, A Ministry of Risk

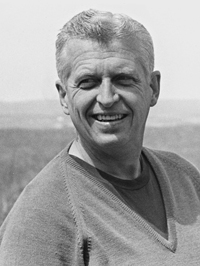

This Saturday, October 5th, would be the 101st birthday of legendary peace activist Philip Berrigan, who passed in 2002. As war and its ugly outcomes ravage the planet, it is good and necessary to reflect on the life, work, and witness of one who gave his life resisting empire and the awful wake of destruction it leaves behind.

This Saturday, October 5th, would be the 101st birthday of legendary peace activist Philip Berrigan, who passed in 2002. As war and its ugly outcomes ravage the planet, it is good and necessary to reflect on the life, work, and witness of one who gave his life resisting empire and the awful wake of destruction it leaves behind.

Philip Berrigan was a World War II soldier, a Catholic priest, a civil rights and anti-war activist who spent 11 years behind bars for nonviolent resistance to war. From the 1950s until 2002 – when he was released from prison just a few months before his passing – Phil was relentless in both articulating resistance to war and embodying that resistance by sacrificing his life and liberty for those victims in the breach.

As the suffering continues today in Gaza and Ukraine, Sudan and Syria and Somalia, in Central America and on our Southern Border, we not only are thankful for the example of Phil Berrigan, but we can recreate that example for the present age of resistance. Nonviolent resistance must always be recreated for contemporary times.

When Gandhi conceived of a march to the sea to hold up a fistful of salt in defiance of the British Empire, he was recreating nonviolent resistance for the present day. When Martin Luther King, Jr. and his colleagues conceived of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, they were recreating nonviolent resistance for the present day. When Philip, his brother Daniel, and their colleagues conceived of entering selective service offices during the Vietnam War to pour their blood on draft files or burn files with homemade napalm, they were recreating nonviolent resistance for the present day.

Philip Berrigan continued his creative nonviolent resistance once the Vietnam War ended by digging graves on the White House lawn in the 1970s under the slogan of “Disarm or Dig Graves.” He was of course arrested for this. That was an intended outcome. Going to prison was a way of going into the breach with the victims.

In 1980, Phil and his colleagues initiated the Plowshares movement when they entered the General Electric Nuclear Facility in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania and hammered on the nose cones of nuclear weapons, symbolically and literally beating swords into plowshares. That Plowshares movement continues to this day with hundreds of people enacting similar resistance efforts.

These were all acts of great creativity designed to capture the public’s attention with their symbolic and literal effect. They were meant to stimulate conversation, shake the citizenry from its slumber, empower and energize the masses. Nonviolent resistance not only requires courage and persistence, but it requires imagination.

Governments, corporations, the military industrial complex are devoid of imagination and creativity on the same level as humankind. This is the advantage that we must press if we are to prevail and save the planet. It is human imagination, our artistic sensitivity, that gives us the edge.

And so, how do we recreate nonviolent resistance for these times? Where is our Ministry of Risk for today?

It can be glimpsed in the brave college encampments that occurred all across the country last spring as students risked their future to stop a genocide against a people they had never met. It comes in the disrupting of so-called Business Fairs where the Merchants of Death hawk their wares for sale as if they were shiny new cars rather than malevolent killing machines. It comes in the serving of subpoenas and the organizing of a people’s tribunal against US weapons makers indicting them for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

But we need more than these. We need extreme creativity, nonviolent actions from the outer borders of our imagination, ones that distill the issues to their symbolic essence. We do this by working in community, nurturing each other’s vision, stimulating our collective imagination so we can clutch in our hand the fundamental symbol of violence and raise it in resistance. We do these things to save lives, others and our own, and in so doing, we become fully human.

For Philip Berrigan, becoming fully human was the goal for himself and for each of us. To become fully human is to resist the temptation to tune out the savagery of the world and the suffering across the globe, to not divert ourselves with the easy materialism available in the United States. To become fully human is to open our hearts and our minds to all of the pain and all of the tragedy and all of the possibilities for redemption that each day presents. To become fully human is to take a risk for victims in the breach.

In a new book on the writings of Philip Berrigan, Philip’s daughter, Frida Berrigan, reflects in the Preface of how her father took care of not only she and her siblings but of the country as well. She writes, “Patch, repair, care. He did that to our bruises and scratches and ripped pant legs, too. Patch, repair, care. Is that what he did to our faith, our community, our national heart too, as he called us to peacemaking, nonviolence, beating swords into plowshares? Patch, repair, care. I think so.”

Phil possessed a great and bold love for humanity, for what he clearly understood to be his brothers and sisters across the globe. Whether it be his family, his community, his country, or the world, Phil sought to patch, repair, and care for all, to embrace a ministry of risk no matter the odds, to pursue that difficult but vital journey of becoming fully human. May we all have the courage, perseverance and creativity to do the same.

Brad Wolf edited the recent book on the writings of Philip Berrigan entitled A Ministry of Risk which was published in April by Fordham University Press. He co-coordinated the Merchants of Death War Crimes Tribunal and is currently chair of the organizing committee of the International People’s Tribunal on the Korean Victims of the 1945 Atomic Bombings. He is executive director of Peace Action Network of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.