It has been hero pitted against hero in the cinemas this spring. DC has the face-off right in the title of its latest big-budget flick: Batman V. Superman: Dawn of Justice. Then came Marvel’s Captain America: Civil War, in which the Avengers disassemble into two warring factions, and Cap scraps with his friend Iron Man. There are interesting similarities between the two tentpoles beyond their central rock ’em sock ’em duels. [Spoilers incoming, dear reader.]

On one level, both physical battles are meant to represent ideological struggles: security vs. liberty, democratic oversight vs. super-heroic independence. In Dawn of Justice, U.S. Senator June Finch (Holly Hunter) chairs Congressional hearings to hold Superman to account. Batman also believes the alien with god-like powers must be put in check, which is what sends the two icons on a collision course. In Civil War, U.S. Secretary of State Thaddeus Ross (William Hurt) strong-arms several Avengers into acquiescing to a set of international accords placing the super-team under United Nations supervision. Captain America goes rogue, leading to a clash between Cap’s refuseniks and Iron Man’s compliant soldiers.

Both regulatory drives are reactions to the fallout from previous super-battles, especially the mass civilian casualties involved. This speaks to the most interesting parallel between the two films: indeed, between the two franchises.

The films of the “Marvel Cinematic Universe” as well as the “DC Extended Universe” dwell on the trauma of mass violence. They are post-traumatic super-hero movies, targeting a post-9/11 audience. Americans are drawn to these cinematic spectacles of destruction and mayhem because they have been living in an age of national trauma for fifteen years.

This long bout of emotional crisis was kicked off by the indelible visuals of 9/11, and then aggravated by the 2008 financial crisis. The terror attacks have not stopped and the job market has not recovered, and so America’s post-traumatic stress disorder has been chronic.

The new wave of blockbuster super-hero movies began with Iron Man(2008). That film’s very first scene was saturated with trauma ripped from the headlines. Tony Stark (Robert Downey, Jr.) is shown as a tech billionaire and devil-may-care playboy: a veritable personification of the go-go nineties, blissfully ignorant of the turmoil to come. Then his whole world is jarringly thrown into upheaval, as the U.S. military convoy taking him through Afghanistan is attacked. His escorts, mostly wide-eyed youngsters overawed by their celebrity passenger, are all massacred. Before he passes out, he finds himself lying in the dirt with a chest full of shrapnel.

When Stark comes to, all he can see is fabric covering his face. The hood is pulled off, revealing that he is bound to a chair, surrounded by his armed and masked kidnappers, and facing a camcorder. One of the terrorists reads something aloud. Is it a list of demands? A preamble to a beheading? At this point, the viewer does not know. Only then does the title card show.

This arresting opening sets the pace for subsequent super-hero movies by evoking the traumatizing imagery of the terror wars: the roadside attacks that killed, maimed, and emotionally devastated so many American troops, and the video-recorded beheadings of American civilians Daniel Pearl and Nick Berg.

Stark becomes Iron Man as a way to deal with both his captors and his shell shock. But his experience in Afghanistan is just the first in a series of traumas that plague him throughout all of the character’s film appearances.

In the culminating battle of The Avengers (2012) moviegoers are presented with a fantasization of 9/11 footage. Again, they see Manhattan under attack. The visuals are replete with screaming city dwellers running through the streets as skyscrapers crumble to the ground. Older and greater existential terrors are referenced when Iron Man nearly dies saving the city from a nuclear missile strike.

In subsequent Marvel movies, the alien attack in Avengers is referred to simply and darkly as “New York.” In Thor: The Dark World, Jane Foster (Natalie Portman) slaps the villainous Loki (Tom Hiddleston) saying, “That’s for New York.” In Iron Man 3, Stark spends the whole movie dealing with his PTSD from “New York.” Stark is still traumatized in the Avengers sequel Age of Ultron. He is tormented by nightmares of fallen comrades in a future apocalyptic battle. His efforts to forestall that catastrophe only beget more catastrophe, which in turn haunts him in Civil War and leads to that film’s main conflict. Thus Stark’s trauma feeds on itself, as he spirals into a multi-film nervous breakdown.

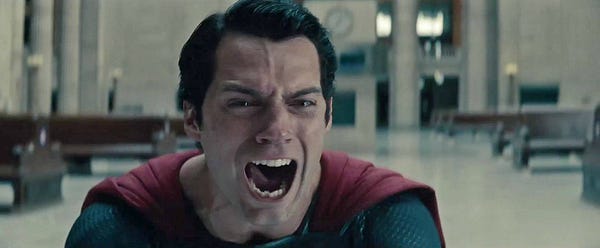

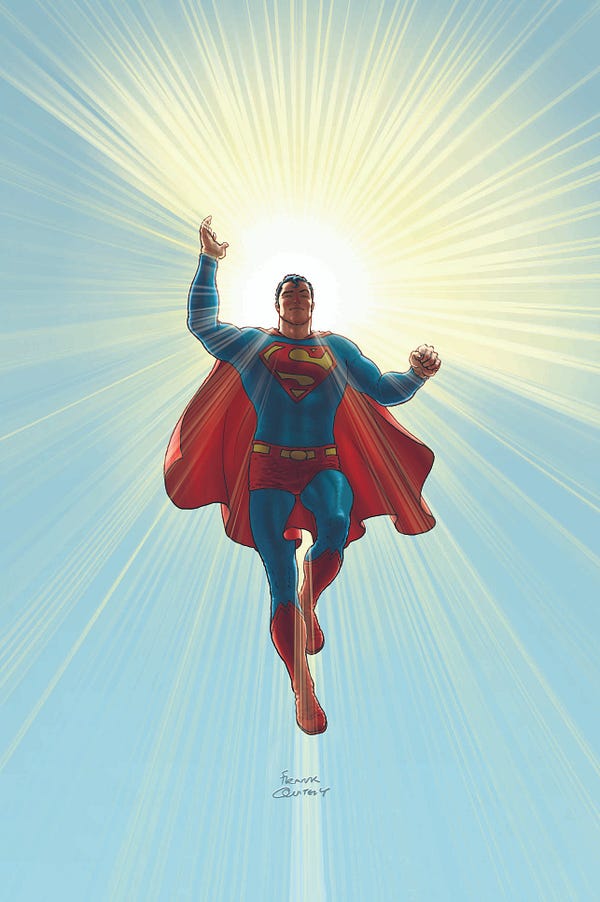

9/11 imagery also pervades the climactic battle of Man of Steel, the movie that started the DC Extended Universe. Traditionally, Superman has been a symbol of hope and rescue. The new Superman (Henry Cavill) is an icon of trauma. In pre-9/11 tales, Superman usually bursts upon the scene in Metropolis by foiling criminals or saving lives from a plane crash, at least at first doing so with zero casualties. The post-9/11 Superman first reveals himself, not to the general public, but to military personell. His introduction is portrayed, not as a source of wonder and inspiration (“Look, up in the sky!”), but as the subject of national security hand-wringing. The first time the citizens of Metropolis even see the red cape flutter is amid a horrific, mass-casualty attack on the city by genocidal Kryptonians. Once again we are subjected to the all too familiar scenes: horrified office-workers scrambling through the dust of collapsed high rises.

And in the current sequel Dawn of Justice, we are subjected yet again: this time through the eyes of Bruce Wayne (Ben Affleck). We see Wayne racing through the streets of Metropolis, desperately trying to reach his employees in the financial sector. He doesn’t even have time to don the cape and cowl and become Batman. He looks up in the sky and sees Superman, not swooping down to save lives, but locked in a Ragnarök struggle with the Kryptonian Zod. The grappling gods hurtle into the Wayne Financial Building. Wayne looks on in horror heat vision melt steel beams, causing the tower to collapse and crush many of his colleagues.

Thereafter Wayne, like Stark, is stricken with PTSD. Batman even suffers from apocalyptic terror dreams, just like his fellow billionaire high-tech hero Iron Man.

The films not only dwell on mass violence, but on how people respond to such trauma: often by throwing themselves into the arms of an alleged protector. After 9/11, the American public rushed to the Federal government for security, acquiescing to a swelling of power for both the national security state (the Patriot Act, the militarization of the police, etc) and the warfare state (wars throughout the Greater Middle East).

In the Marvel and DC movies too, the government responds to attacks by grasping for greater power. Individuals can no longer be trusted with the freedom to decide how to use their special abilities. Security demands that super-heroics be overseen, even commandeered by the government. As discussed, there were the Senate hearings in Dawn of Justice and the socialization of the Avengers in Civil War. In Man of Steel, a general asks Superman, “How do we know know you won’t one day act against America’s interests?” Iron Man 2 also had Congressional hearings, in which a Senator demanded that Tony Stark hand the Iron Man armor over to the U.S. military. A military officer later confiscated one of the suits on behalf of the government after he deemed Stark too irresponsible to use it.

Attacks are also used as an excuse for embracing preemptive violence. The principle of preemption was the essence of the Bush Doctrine. This was complemented by the Cheney or “One Percent” Doctrine, according to which a threat with even a mere one percent probability of being real would be treated by US policy as if it were a certainty. The invasion of Iraq over non-existent weapons of mass destruction was the Bush and Cheney Doctrines in action.

In Dawn of Justice, Batman explicitly expresses the Cheney Doctrine in reference to Superman, saying, “He has the power to wipe out the entire human race, and if we believe there’s even a one percent chance that he is our enemy we have to take it as an absolute certainty… and we have to destroy him.”

But as Captain America told Iron Man in Age of Ultron, “Every time someone tries to win a war before it starts, innocent people die. Every time.”

Indeed, the preventive war on Iraq led to over a million deaths, the rise of ISIS, and more terrorist slaughters of innocents. That terrorism elicted calls for more war, which is only breeding more chaos and terrorism.

Similarly, the Marvel films have been an ongoing cycle of intervention: preemptive action causes blowback, which elicits further preemption, which causes further blowback, etc. In Avengers it is revealed that, in response to an alien attack on a small town in Thor, SHIELD tried to use alien technology to make weapons of cosmic destruction. This led directly to the alien invasion of New York. In response to that attack, SHIELD deployed a system of mass surveillance and preemptive assassination in Captain America: Winter Soldier, and Stark tried to create an artificial intelligence to police the world in Age of Ultron. Both projects resulted in still more death and destruction. And the fallout from all these disasters (as well as Stark’s guilt over his Ultron A.I.) resulted in the preventative regulations and turmoil in Civil War. As Thor says in Avengers, “You speak of control, yet you court chaos.”

Governments often court chaos, as if they feed on public trauma. Indeed, they do. War torn psyches are the health of the State. Again, people often react to trauma by throwing themselves into the arms of an alleged protector. And most people have imbibed the myth that the State is our ultimate protector. As the recently departed Prince sang, “Would you run to me if somebody hurt you, even if that somebody was me?”

The State afflicts us with a subtle case of “learned helplessness”: a condition professional torturers strive to instill in their victims. Emotionally tormented by state-precipitated war and terrorism, we give ourselves over — liberty, property, and all — to our very tormenters. Our captivity becomes precious to us, and we look upon our captors as saviors. The State is the Stockholm Syndrome institutionalized.

Maybe super-hero disaster films offer catharsis to post-9/11 moviegoers. Or perhaps they only serve to aggravate and perpetuate our national PTSD. In any case, the State would relish seeing the super-hero continue to degrade into an embodiment of trauma: a suitable idol for hopeless and helpless population of subjects. We must not let that happen.

The classic super-hero is an aspirational figure, representing confidence and human potential: a proper icon for a free people. Let’s stop wallowing in the dismal, hackneyed narratives of terror. Let’s overcome the State’s efforts to spiritually cripple us. Let the personified ideals we call super-heroes once again soar into the bright and limitless sky. And by emulating such lofty models, let us restore our emotional health, our self-reliance, our faith in freedom.

Also published at Medium.com and DanSanchez.me.

Dan Sanchez is Digital Content Manager at the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE.org), contributing editor at Antiwar.com, and an independent journalist for TheAntiMedia.org. Follow him via Twitter, Facebook, or TinyLetter.