Serious conservatives, men such as Scott McConnell of The American Conservative and economist Paul Craig Roberts, along with such eminent libertarians as Justin Raimondo of Antiwar.com and Lew Rockwell, are raising a surprising question: do the war in Iraq and the Bush administration’s desperate attempts to shore up support for that war have a whiff of fascism about them? In the Feb. 14 issue of TAC, McConnell quotes his old history professor at Columbia, Fritz Stern, writing in The New York Times:

“Now the word ‘freedom’ has become a newly invoked justification for the occupation of a country that did not attack us, whose people have not greeted our soldiers as liberators. …

“The world knows that all manner of traditional rights associated with freedom are threatened in our own country. The essential element of a democratic society – trust – has been weakened, as secrecy, mendacity, and intimidation have become the hallmarks of this administration. …

“Now freedom is being emptied of meaning and reduced to a slogan.”

To these wise words, Scott McConnell adds his own:

“I don’t think there are yet real fascists in the administration, but there is certainly now a constituency for them hungry to bomb foreigners and smash those Americans who might object. And when there are constituencies, leaders may not be far behind. They could be propelled into power by a populace ever more frustrated that the imperialist war it has supported generally for the most banal of patriotic reasons cannot possibly end in victory.”

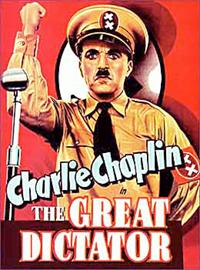

These voices, which should be heard thoughtfully, are pointing to a real danger. Yet I do not think that danger can rightly be labeled fascism. Beyond the facts that W as dictator suggests not so much Hitler or Mussolini as Charlie Chaplin and that the greatest threat to freedom in America is the left’s ideology of cultural Marxism, there is a larger problem: the intellectual core of fascism itself.

These voices, which should be heard thoughtfully, are pointing to a real danger. Yet I do not think that danger can rightly be labeled fascism. Beyond the facts that W as dictator suggests not so much Hitler or Mussolini as Charlie Chaplin and that the greatest threat to freedom in America is the left’s ideology of cultural Marxism, there is a larger problem: the intellectual core of fascism itself.

Fascism is not merely dictatorship. The core idea of fascism is will as the highest virtue. Fascism sought to drop the whole Judeo-Christian content of Western culture and return to the values of the classical world, where power was the greatest good. (What astonished Greeks and Romans about Christianity was not that it had a Savior who died and rose from the dead; many Eastern mystery cults claimed the same. What astonished them was that these Christians’ God said, “I came not to be served, but to serve.”) To fascists, the exercise of power, will, was the supreme moral act.

This was a serious error, because it turned an instrumental value, will, into a substantive value. In reality, will is good or evil depending upon what is willed. By attempting to turn will into a substantive value, fascism destroyed itself: will led to Mussolini’s entry into World War II (had he remained neutral, like Franco, he would probably have survived Hitler’s defeat), to Hitler’s offhand declaration of war on America (even after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt would have had trouble getting an offensive declaration of war on Germany through Congress) and, ultimately, to the Holocaust: when the Nazis’ original aim of expelling the Jews from Europe became impossible because there was no place to send them, will demanded a Final Solution.

Thankfully, America has a long way to go before triumph of the will could become the American creed. The Christians who make up George W. Bush’s political base would gag well before reaching that point; they know their Bible better than that.

I would suggest that, instead of fascism, the danger now facing America is one of the many ills released from that Pandora’s box, the French Revolution: abstract nationalism. As Burke pointed out, conservative patriotism is very different from the abstract nationalism of la Patrie. It is a concrete attachment to our own places: our own valleys or towns, our farms, hills, or plains.

Abstract nationalism, what Martin van Creveld calls the “state as an ideal” in his book The Rise and Decline of the State, has spread widely in America. As conservatives, we need to do a better job of explaining to our fellow citizens why that kind of nationalism is radical, not conservative. But van Creveld’s book also points to the likely fate of such a nationalism: it will crumble after it fails in war.

In Europe, the state as an ideal died in World War I, in the mud at places like the Somme and Verdun. I suspect that the same thing is going to happen here after the American people have to confront the reality of America’s defeat in Iraq. Bush’s wild Wilsonianism is out of time; it is a ghost from an era long past, an illusion that is now sustained only by the public’s trust that somehow our troops unquestionable valor in Iraq will bring victory. When it becomes clear to that public that valor alone is not enough, that a failed strategy brings defeat no matter how courageously soldiers and Marines may fight, the grand illusion will be followed by a profound bitterness and a turning inward. That turning inward could be a good thing for conservatives, if we can lead it toward a restoration of the American republic as a curative for the follies of empire.

There is one not unlikely event that could bring, if not fascism, then a nationalist statism that would destroy American liberty: a terrorist event that caused mass casualties, not the 3,000 dead of 9/11, but 30,000 dead or 300,000 dead. We will devote some thought to that possibility in a future column.