This article originally appeared at TruthDig.

“Strange indeed did it appear to me to find so many names, familiar household words, as enemies—the very names of officers in our own army. … How uncomfortably like a civil war.” —British Lt. John Le Couteur upon visiting an American Army camp (1813)

Americans, sadly, know little of their own history. Who among us recalls anything about the War of 1812? Few, if any. What those few do tend to remember are patriotic anecdotes from a long-ago war: Andrew Jackson mowing down foolish redcoats at the Battle of New Orleans; Dolly Madison saving the portrait of George Washington just before the British burned down the capital; Francis Scott Key penning “The Star Spangled Banner” as he observed the bombardment of Fort McHenry.

These are carefully selected snapshots in an otherwise hazy war. None of this comes together—except in the minds of academic historians—into anything resembling a coherent tale. Why did we fight? Was it necessary? Did we win? The cherry-picked anecdotes of jingoism answer none of these vital questions, but ask them we must. The decision to take a nation to war, to send young men into combat, is a solemn one indeed. And the War of 1812 is one of only five wars the United States has officially declared.

The conflict deserves our attention for the last reason alone, but also because the war and its complexities are instructive to today’s engaged citizen. Though it is rarely remembered this way, in some ways this was a civil war, fought between men who spoke the same language, practiced the same religion and had remarkably similar customs. It was also a war of conquest, suffered worst by the native peoples of the Ohio Country and Upper Canada. It was, too, a sideshow theater of the broader Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815); as historian Gordon Wood wrote, “The U.S. was born amidst a world at war.”

This much is certain: It was a peculiar war, full, in equal measure, of paradox and farce. Thousands died, but little was gained. In some cases brother fought brother. And, in a strange tinge of irony, the side that best championed liberty was not always American. For all its complexity, perhaps because of it, the War of 1812 deserves a fresh look, and our attention.

An Unnecessary War? The Strange Path to Conflict

“[The War of 1812 was] a metaphysical war, a war not for conquest, not for defense, not for sport, [but rather] a war for honour, like that of the Greeks against Troy.” —Republican politician John Taylor of Virginia

Why fight another war with Great Britain? Why fight it in 1812? These are, and were, important questions for the leaders of the nascent American republic. Most histories, and most rhetoric of the day, focused on British insults inflicted upon the American state. Much of the controversy was naval, and involved the American struggle to protect its neutral rights to trade with any and all of the warring parties in Europe. Impressment—the British practice of boarding U.S. merchant ships and capturing or forcing the enlistment of American sailors (the Brits claimed they were all British navy deserters)—was considered the most heinous affront of all.

Still, this was an odd grievance to start a war over. After all, the British Empire had a massive army and unparalleled naval strength. The young American republic was unprepared for war and nearly defenseless. Besides, the British had a point. Though they often captured genuine American citizens, America’s own secretary of the treasury estimated that up to one-third of American sailors were indeed British deserters. And it makes sense: The U.S. paid more, had lower standards of discipline and wasn’t at war! The British were at war; in fact they were engaged in an existential struggle with French Emperor (and continent conqueror) Napoleon Bonaparte. They needed those deserters back to man the navy that protected the British Isles. Stranger still, soon after the U.S. declared war (this was a war of choice!), Britain repealed the Orders in Council, the very policy that resulted in impressment. Once President James Madison received word of this reversal, the U.S. might have rescinded the declaration and saved thousands of lives. It did not.

Part of the reason is this: The War of 1812 was about honor as much as anything else. The ancient Greek historian Thucydides claimed that nations go to war for either “fear, honor, or interest.” Wars fought primarily for honor rarely appear in the course of history, but this was one such case. The Americans felt the British had disrespected them, were trying to maintain the U.S. as a de facto colonial dependency. Many Republican (the party of Thomas Jefferson and Madison) leaders became avid “war hawks”—adding that term forever to the American lexicon—and believed that war with Britain would be a regenerative, purifying and unifying act. They would be proved wrong, but not before thousands perished in two and a half years of combat.

There were other motives for this war besides the affirmation of neutral rights and the reclamation of national honor. Many Westerners (who tended to be avid Republicans) had long coveted Canada, then a British colony. In fact, the Continental Army had previously attempted, unsuccessfully, to conquer Canada during the Revolutionary War. And, strikingly, the first American constitution, the Articles of Confederation, claimed the province of Canada as a future state within the expanding American union. In 1812, “Free Canada!” became a rallying cry, and the U.S. would spend most the war in this fruitless endeavor. We were the invaders!

Other American Westerners, especially in the Ohio and Michigan Country, feared and loathed the Native Americans who had the gall to demand autonomy. Ever-expansive settlers wanted all land east of the Mississippi and saw war with Britain as a means to that end. The Brits, after all, were allegedly arming and funding the very native peoples who had the propensity to raid American settlements. The powerful native confederation—recently brokered by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh—had to be broken. War would make that possible.

Seen through a wider lens, the American declaration of war is discomfiting. By attacking Britain, the young republic was now tacitly allied with the dictator Napoleon Bonaparte of France in his ongoing war with the United Kingdom—a hypocrisy the British relished in pointing out.

There were many other ironies to this war. The British didn’t want it, and the weaker Americans insisted upon it. The war didn’t unite the country. On the contrary it fiercely divided the Federalist (which dominated in New England) and Republican (powerful in the South and West) political factions. Indeed, the Senate vote on the declaration of war was the closest in American history. The paradoxes just piled up. The Southern and Western senators voted for war, even though the impressment of American sailors most affected New England. The Republicans clamored for war even though their party supposedly hated standing armies and militarism. To wage this war, Madison and the Republicans would have to restrict trade, build a military establishment and coerce obedience—the very actions most abhorred in Republican ideology.

This would prove to be a strange conflict indeed.

David or Goliath: The Myths of 1812

“Many nations have gone to war in pure gayety of heart, but perhaps the United States were the first to force themselves into a war they dreaded, in the hope that the war itself might create the spirit they lacked.” —Henry Adams, great-grandson of President John Adams, in 1891

In Americans’ collective memory, then and now, the U.S. played David to Britain’s Goliath. Our fragile little republic, so the story goes, stood up to the bullying British and—just barely—saved our independence from the imperial enemy. But is it so? Just who was David and who was Goliath? That, of course, depends on one’s point of view.

In point of fact, the British were busy and spread thin. They had been at war with the powerful French on a global scale for some 19 years. The only British force within striking distance of the U.S. was in Canada, and this—in a stunning reversal of the popular myth—represented a stunning mismatch. There were barely 500,000 citizens in Canada, compared with about 8 million in the United States. The British had only a few thousand regular troops to spare for the defense of this massive Canadian landmass. The Americans might be unprepared, and might prove “bad” at war, but by no means was the initial deck stacked against the large and expansive American republic.

The myth of American defensiveness is also belied by a number of other inconvenient facts. The United States declared this war, a war that Britain had no interest in fighting. Furthermore, despite the exaggerated claims of war hawks and patriots of all stripes, this was not a Second War of Independence. There is no evidence that the British sought to reconquer and colonize the mammoth American republic. Any land seizures were planned to be used only as bargaining chips at an eventual peace settlement. Tied down in an existential war of its own, Britain had neither the capacity nor intent to resubjugate their former colonists.

‘Free Canada’: Civil War in the Northern Borderlands

“The acquisition of Canada, this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching.” —Thomas Jefferson (1812)

“People speaking the same language, having the same laws, manners and religion, and in all the connections of social intercourse, can never be depended upon as enemies.” —Baron Frederick de Gaugreben, British officer, in 1815

No one seems to know this (or care), but the United States had long coveted Canada. In two sequential wars, the U.S. Army invaded its northern neighbor and intrigued for Canada’s incorporation into the republic deep into the 19th century. Here, on the Canadian front, the conflict most resembled a civil war.

Canada was primarily (though sparsely) populated by two types of people: French Canadians and former American loyalists—refugees from the late Revolutionary War. Some, the “true” loyalists, fled north just after the end of the war for independence. The majority, however, the “late” loyalists, had more recently settled in Upper Canada between 1790 and 1812. Most came because land was cheaper and taxes lower north of the border. Far from being the despotic kingdom of American fantasies, Canada offered a life rather similar to that within the republic. Indeed, this was a war between two of the freest societies on earth. So much for modern political scientists’ notions of a “Democratic Peace Theory”—the belief that two democracies will never engage in war. Britain had a king, certainly, but also had a mixed constitution and one of the world’s more representative political institutions.

In many cases families were divided by the porous American-Canadian border. Loyalties were fluid, and citizens on both sides spoke a common language, practiced a common religion and shared a common culture. Still, if and when an American invasion came, the small body of British regular troops would count on these recent Americans—these “late” loyalists—to rally to the defense of mother Canada.

And came the invasion did. Right at the outset of the war in fact. Though the justification for war was maritime and naval, the conflict opened with a three-pronged American land invasion of Canada. The Americans, for their part, expected the inverse of the British hopes—the “late” loyalists, it was thought, would flock to the American standard and support the invasion. It never happened. Remarkably, a solid base of Canadians fought as militiamen for the British and against the southern invaders. Most, of course, took no side and sought only to be let alone.

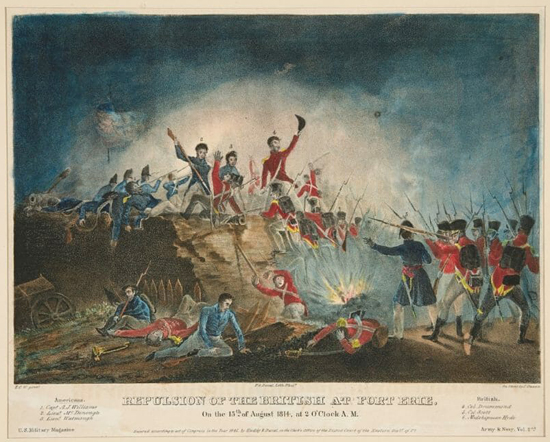

It turned out the invading Americans found few friends in Canada and often alienated the locals with their propensity for plundering and military blunder. Though the war raged along the border—primarily near Niagara Falls and Detroit—for nearly three years the American campaign for Canada proved to be an embarrassing fiasco. Defeats piled up, and Canada would emerge from the war firmly in British hands. In the civil war along the border, the Americans were, more often than not, the aggressors and the losers.

Indians, Britons, Slaves and the Real Losers of the War of 1812

“[The Indians] have forfeited all right to the territory we have conquered.” —Gen. Andrew Jackson

“My people are no more! Their bones are bleaching on the plains of the Tallushatches, Talladega, and Emuckfau.” —Creek Chief Red Eagle

The U.S. was a republic, Britain a monarchy. Thus, in Americans’ collective memories the United States must have been fighting for liberty, for democracy. But was it? Britons saw matters rather differently. They argued that their mixed constitution, providing for a king and the Houses of Lords and Commons, best protected liberty and stability at home and abroad. The British actually believed (not without some merit) that only they protected Europe, and by extension America, from the expansive tyranny of Napoleonic France and that the Americans were ungrateful for this sacrifice.

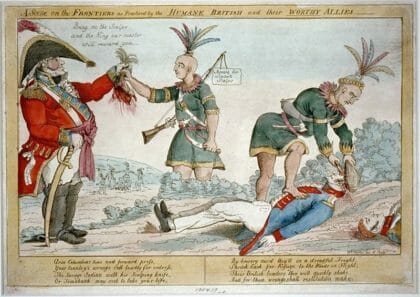

Furthermore, when it came to treatment of blacks and Native Americans, it seems the British better upheld our modern conceptions of liberty and equality. Most Americans felt a mix of fear and hatred for the local Indian tribes. Settlers perceived the threat of Tecumseh’s Indian confederation to be existential. These Westerners called for a conquest of Canada to remove British support for the tribes and exterminate the Indians once and for all.

The British viewed the Native Americans in a completely different way. And the natives saw the Brits as much less of a threat than the more populous and encroaching Americans. The British supplied, funded and generally respected the autonomy of the Canadian and Ohio Country tribes. With so few English settlers in the colony, British leaders counted on native allies to defend Canada and were more than happy to accept and recognize an Indian buffer state on the frontier. They did so, no doubt, out of self-interest but were still far more congenial to the tribes than the hated American settlers.

Therefore, in a replay of the Revolutionary War, the vast majority of natives actively sided with, and often fought for, the British. This would prove to be a fateful mistake. Tecumseh’s confederation was eventually defeated (and Tecumseh himself killed) at the Battle of the Thames, and the Creek Indians were devastated by the brutal tactics of Andrew Jackson in the South. The Indians emerged from the war defeated and without the reliable support of the British, who quickly sold them out at the peace conference. Never again would native tribes maintain any autonomy east of the Mississippi or prove able to stand up to the far more numerous Americans. The War of 1812, was, for the native peoples, an unmitigated disaster.

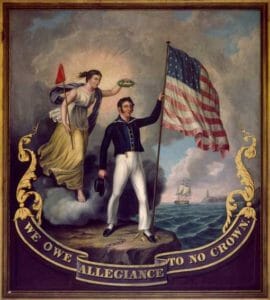

In yet another replay of the Revolution, black American slaves deeply rejected American proclamations of a war for liberty and equality. The ascendant American Republicans running the country were powerful in the South and respected the fears of slaveholders in that region. Though desperately short of recruits, the Americans refused to enlist free blacks or slaves into the Army. On the contrary, many slaves escaped their plantations and either ran to British lines or (in many cases) swam to British ships—places where they were much more likely to find the liberty that the Americans falsely professed for all. The British offered freedom, an enlistment bounty and free land to runaways who joined up. Some 600 free blacks or slaves became Royal Marines!

If the War of 1812 was a war for freedom, it was for a very narrow and limited freedom indeed. Republicans extolled their commitment to liberty and equality, but those sentiments extended only to the white men of the young republic. Britain, which had already abolished slavery, would for blacks and Indians prove the better beacon of liberty.

Treason at Home? Federalists, Republicans and the Politics of War

The War of 1812 also constituted a political civil war at home between the ruling Republican Party and the opposition Federalist Party. The Federalists had much to lose and little to gain from the war. They predominated in New England and in coastal ports and relied on trade with Britain to earn a decent living. They had few visions of grandeur about western land annexations or a conquest of Canada. Furthermore, the more aristocratic Federalists favored Britain in its war with revolutionary and then Napoleonic France, seeing Britain as a rock of stability against a tide of chaos and conquest from dictatorial France.

Many Federalists continued to illegally trade with the Brits, smuggled goods to Canada and seemed to actively oppose the war. Republicans dubbed them traitors, while the Federalists saw themselves as prudent realists. Some Federalists even considered secession from the union and the formation of an independent New England republic. Most, however, never went that far.

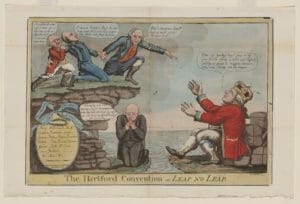

Still, in 1814, after two years of indecisive war, the Federalist Party would unknowingly sign its own death warrant. New England Federalists sent delegates to a convention in Hartford, Conn., that meant to oppose the war and recommend new amendments to the Constitution. And, in truth, these amendments weren’t all bad. They called for the repeal of the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted slaves as partial humans for representation sake and gave extra political weight to the South. They also sought to require a (sensible?) two-thirds majority in Congress to declare future wars, and to limit presidents to a single term in office.

Was this, as some claimed, tantamount to treason during a period of active hostilities? Indeed, some Federalists actively discouraged military enlistment and the withholding of federal taxes to fund the war, and some New England governors refused to send their state militias on offensive campaigns. But was this treason or principled opposition to an ill-advised war? The country was divided in answering the question, similar to some issues that remain with us.

The Federalists might have been right, in fact, both ethically and constitutionally, but the Hartford Convention’s luckless timing destroyed them politically. Just as the delegates were meeting, the Republicans were securing a status quo peace treaty and Gen. Andrew Jackson was winning a staggering victory over the British at New Orleans (a few weeks after the treaty had been signed but before word of the peace reached the Americas). The Republicans waved the bloody shirt and painted the Hartford Convention as a treasonous betrayal. The Federalists would never again gain a majority in either house of Congress or run a viable presidential candidate. They were finished. Perhaps opposition to war, even a less than popular war, never pays politically.

Ironic Outcomes: A Costly Draw

“The War of 1812 is the strangest war in American history.” —Historian Gordon Wood (2009)

The Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war, changed nothing. There was no change of borders, and the British said nothing about impressment—the purported casus belli! So just what had those thousands died for?

Certainly it was no American victory that forced the British to the peace table. By 1814 the war had become a debacle. Two consecutive American invasions of Canada had been stymied. Napoleon was defeated in April 1814, and the British finally began sending thousands of regular troops across the Atlantic to teach the impetuous Americans a lesson—even burning Washington, D.C., to the ground! (Though in fairness it should be noted that the Americans had earlier done the same to the Canadian capital at York.) The U.S. coastline was blockaded from Long Island to the Gulf of Mexico; despite a few early single ship victories in 1812, the U.S. Navy was all but finished by 1814; the U.S. Treasury was broke and defaulted (for the first time in the nation’s history) on its loans and debt; and 12 percent of U.S. troops had deserted during the war.

The Americans held few victorious cards by the end of 1814, but Britain was exhausted after two decades of war. Besides, they had never meant to reconquer the U.S. in the first place. A status quo treaty that made no concessions to the Americans and preserved the independence of Canada suited London just fine.

So who were the winners and losers of this indecisive war? American land speculators and frontiersmen, to be sure, for they had broken Indian power and opened up millions of acres for western settlement. The biggest losers, of course, were those very Indians, who saw their last hopes for autonomy fade away. They were now, once and for all, a conquered people. The Federalists lost too, as a political party, and as a viable ideology. Republicans would remain ascendant—with no serious opposition—for some two decades after the war. So if New England and the natives lost, the Republicans, Southerners and Westerners emerged victorious.

Nor is it clear which side truly fought for anything resembling (our modern conception of) liberty. And, in the end, after thousands had died (more from disease than combat) on both sides, Canada remained British and nothing had been done about neutrals’ rights on the high seas. Indian power had been broken and the Federalists disappeared, but little else changed.

Perception and Reality: Remembering the War of 1812

“[The War of 1812] has revived, with added luster the renown which brightened the morning of our independence: it has called forth and organized the dormant resources of the [American] empire: it has tried and vindicated our republican institutions … which consists in the well earned respect of the world.” —“A Republican citizen of Baltimore” writing in a newspaper (1815)

Still, perhaps inevitably, both sides would claim a victory of sorts. Nationalist sentiment exploded among ascendant American Republicans, who claimed they had won a “second revolution” and smitten an empire. The decisive victory at the Battle of New Orleans, fought after the treaty had been negotiated, gave Americans the impression of victory. Since the end of the Napoleonic Wars made the issues of impressment and neutrals’ rights moot, the Republicans could also claim victory on the seas—even though the British agreed to nothing of the sort in the Treaty of Ghent. To a fervently patriotic American majority, the war seemed to vindicate both the nation’s independence and its republicanism. Indeed, more American towns and counties (57) are now named for President Madison than any other president—including George Washington!

Canadians, too, claimed a victory and developed a new nationalism and origins myth around their collective defeat of the American invaders. Americans may know and care little about the War of 1812, but not so the Canadians. In Canada, the war is widely seen as a pivotal, patriotic event, a noble defense of the northland against marauding American invaders. The British, well, they were mostly just glad all these wars were over; they never gave much attention to the American sideshow in the first place. From their perspective, they had punished the petulant Americans (even burning their capital!) and conceded nothing at the negotiating table.

So ended and so was remembered an utterly peculiar conflict.

It was a dumb war, in retrospect: unnecessary and ill-advised. Some wars, even American wars, have proved to be just that—wasteful. At best the War of 1812 resulted in a draw; a draw that cost the lives of many thousands; a draw that destroyed any hope of Indian autonomy east of the Mississippi. Still, like most wars, this conflict stirred up patriotism and jingoism, among Americans and Canadians. War, many politicians (usually miles away from the fighting) believe, can be a regenerative act, renewing the spirit of patriotism and uniting competing factions. That is a myth. It is almost never this way. Wars tend to be messy, divisive and inconclusive, and that was especially true of this conflict. Things are lost when a nation embarks on combat: civil liberty at home, human empathy at the front, all sense of realism and proportion in the combatants’ capitals.

American mythmakers (two centuries worth of them) have spun the War of 1812 into a nationalistic yarn. They have focused on the victories of Andrew Jackson, ignored the U.S. debacles in Canada and turned an obscure song (set to the tune of a British drinking ballad)—“The Star Spangled Banner”—into a national anthem. How ironic, then, that the anthem, a war song—which today stirs up so much controversy on football Sundays—emerged from a conflict that should never have been fought and that we didn’t really win.

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

• James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle

and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,”

Chapter 9: “The Early Republic, 1789-1824” (2011).

• Alan Taylor, “The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects,

Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies” (2010).

• Gordon Wood, “Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815″(2009).

Major Danny Sjursen, an Antiwar.com regular, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge. He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kansas. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris ‘Henri’ Henrikson.

[Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.]

Copyright 2018 Danny Sjursen