Much ink has been spilled on the cause of our current American malaise. Immigration, race, integration, and economics have been bandied about as causes for our current political strife. However, all of these are insufficient to explain our current political and cultural turmoil. More than any other single factor, the economic, geographic, and racial disparities in military sacrifice during the Global War on Terrorism have fractured our politics, strained cultural cohesion, and undermined Americans’ confidence in elite institutions. While economic issues and immigration have undoubtedly polarized American politics, the burden borne by some segments of society have compounded these issues and made our politics almost irreconcilable. While the relationship between military sacrifice and political realignment has been observed by some academics, and journalists of both the left and the right, it remains an understudied and underappreciated facet of our political and cultural moment.

To illustrate this case, this article will use a computational analysis of U.S. Defense Department casualty records, county income data, and population statistics. Of course, death was not the only negative outcome of US service during the Global War on Terrorism. As many as 53,000 Americans were wounded during service in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, depression, substance abuse, and suicide have also taken their toll on communities throughout the United States. This collective stress has transformed American politics and strained the social fabric.

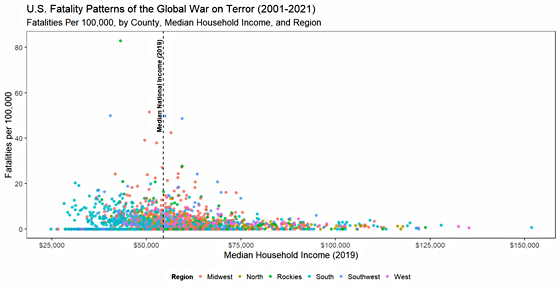

Throughout the Global War on Terrorism, the working and middle classes have paid a disproportionate cost in life and limb. While it is cliché to point out that the rich declare wars and the poor fight them, this has become especially true in modern America. The combination of an all-volunteer force coupled with mass deindustrialization furthered the economic disparities present within the armed forces. The data presents a stark picture. Counties which hold a median income under $75,000 a year endured 2.21 war fatalities per 100,000 county residents. The richest 100 counties in the United States endured 1.22 fatalities per 100,000 residents, 21 of those counties are in Virginia or Maryland, and have benefited financially from the US government’s interventionist foreign policy.

Figure 1: Data Source: Defense Department Defense’s Casualty Analysis System (DCAS), and Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture.

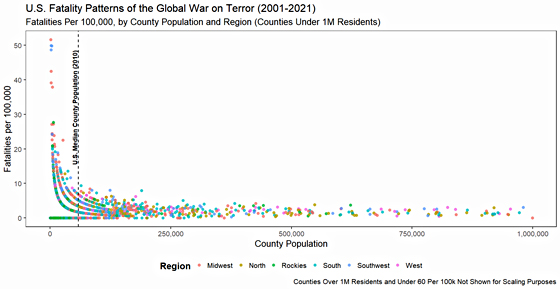

In addition to economics, major sectional disparities exist. Proportionally, small towns and rural counties have been hit the hardest by the cost of the Global War on Terrorism. Already riven by economic decline, small communities throughout the United States have sent their sons and daughters into military service at higher rates than their urban counterparts. As a result, rural America has sacrificed its populations at significantly higher rates than those in big cities and suburbs.

Figure 2: Data Source: Defense Department Defense’s Casualty Analysis System (DCAS), and 2019 US Census data.

Disparities have also occurred among different regions of the country. The Southwest, Rocky Mountain West, and the Midwest have all incurred fatality rates above the national average. This burden has resurrected a long dormant desire for noninterventionism. In the early 20th century, Americans living in the interior often viewed themselves to be in a colonial relationship with the coasts. As a result, they developed brands of conservatism and progressivism known for their opposition to foreign entanglements. Suppressed by the rise of the so-called "vital center," these strains of foreign policy restraint largely vanished until decades of hot war fractured American political orthodoxies

Southerners, especially rural southerners, suffered a similar rate of loss to the War on Terror, 2.25 fatalities per 100,000 people. Historically, the South was one of America’s most martially inclined regions. From World War II until the end of the Cold War, southern support for U.S. foreign policy goals deviated little. However, after decades of bloodletting, many southerners cheered when a political novice bucked his own party’s establishment and declared that the war in Iraq "was a big fat mistake."

By comparison, northern and west coast states have suffered considerably lower rates of military fatalities, 1.9 and 2.17 per 100,000 respectively. This regional disparity in military sacrifice has amplified an existing rural v. urban divide and contributed significantly to the active realignment of American politics.

|

Region |

Population |

Fatalities |

Per 100,000 |

|

Southwest |

37,348,108 |

965 |

2.58 |

|

Rockies |

13,614,255 |

329 |

2.41 |

|

Midwest |

66,927,001 |

1,556 |

2.32 |

|

South |

85,658,832 |

1,928 |

2.25 |

|

West |

49,880,102 |

1,087 |

2.17 |

|

North |

55,317,240 |

1,053 |

1.9 |

|

All |

308,745,538 |

7,037* |

2.27 |

Figure 3: *119 fallen soldiers did not have a home state of record in the DCAS dataset or enlisted from a region outside of the United States. Data Source: Defense Department Defense’s Casualty Analysis System (DCAS), and 2019 US Census data.

Lastly, significant racial disparities exist among America’s war dead in the 21st century. 82% of US casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan were white, despite comprising 57% of the US military and approximately 60% of the US population. This prolonged burden of combat, in concert economic woes and an the opioid crisis, set the groundwork for Donald Trump to make noninterventionism an main plank of his campaign. Trump’s co-opting of this wartime anguish, however sincere or opportunistic significantly aided his 2016 victory. The Trump campaign coupled with the decentralization of the internet helped to forge these different regions into a larger populist movement glued together in large part by shared military service and sacrifice.

These disparities in wartime losses expounded upon another conflict, the culture war. Conservatives, who are overrepresented among veterans, have come to view the foreign policy class and similar coastal elites (to include large swaths of the GOP) with abject disdain. While it is true that the US has been awash in militaristic pageantry since 2001, the right sees the national mood as inherently hostile if not downright contemptuous of them and their values. In their eyes, conservative principles are routinely mocked by the same social class which has sent them or their children to die needlessly abroad. Their home states are referred to derisively as "fly over country." They have been called "bitter clingers" and "deplorables." Their religion and patriotism are routinely mocked, as are their cultural values on abortion and guns. Their views on constitutional government are ridiculed as both ahistorical and outdated. They are routinely labeled as racists, sexists, Nazis, homophobes, and so on. Worst of all, they are increasingly compared to those that they fought and are seen as a growing terror threat.

Many of these insults are hurled by the same political figures who initiated overseas intervention, media figures who advocated for them, and the pundits who rationalized them. The class of men and women who are being asked to fight America’s wars are routinely disrespected by the class of men and women who start and champion these wars. This is no way to govern a republic.

The class and culture divide would be enough to sow distrust, but the foreign policy establishment has not instilled confidence in its ability to manage international affairs or prosecute its wars. The Iraq war fiasco led to the election of President Obama, who despite running on a platform of a humble foreign policy, expanded America’s war total. His failure elicited a response from the right, and among the opponents of Obama’s wars in Libya, Syria, and Yemen were Tea-Party Republicans. Given his unwillingness or inability to end America’s endless wars it, should not come as a surprise that as many as 1-in-10 Obama voters pulled the lever for Trump in 2016. Twenty years of bloodletting in the greater Middle East as gone horribly. Iraq is an Iranian client state. Afghanistan has fallen back into the hands of the Taliban. Libya is teetering on the brink of collapse. Syria continues to be mired in civil war. If failure and incompetence were not enough, the elite foreign policy establishment routinely lied to themselves and to the American people about the progress in these wars. Should it be a surprise that distrust for institutions is rampant among Americans, particularly those segments of the population which have shed their blood to maintain them? In this environment of disdain, incompetence, and duplicity, it is no accident that large swaths of America view “the experts” with hostility.

To cool the temperature in American society, we must reckon with the US government’s interventionist foreign policies and their impact on sectional and class tensions. Americans need to take stock of how open-ended war is tearing at the fabric of civil society. We ought to recognize that dissent, distrust, and yes, even hatred have a history. If the United States is to endure as a republic, we cannot place unfair burdens upon society’s members and then belittle them, their culture, or their political grievances. These forces are not beyond our control; human action brought us to this point. The cumulative weight of foreign and social policy coupled with millions of individual interactions have created these tensions. We can do otherwise.

Brandan P. Buck is a PhD student in history at George Mason University. He is currently researching the domestic politics of U.S. in the 20th century. He is a former intelligence professional and veteran of Operation Enduring Freedom. He can be reached at bbuck@gmu.edu or brandanpbuck.com.