A Swarm (or “Plague”) of Locusts

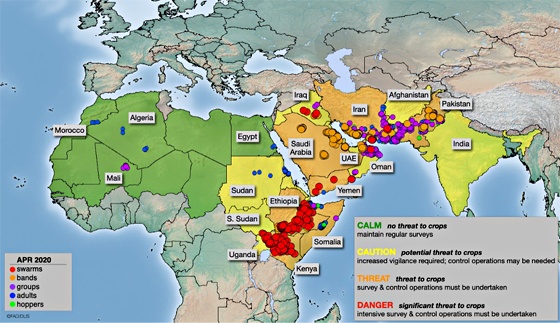

Locusts seem like something out of a science-fiction story or a Biblical apocalypse: miles-wide clouds of voracious insects descending from above and stripping the land bare of every scrap of vegetation. One almost sees Charlton Heston as Moses invoking the wrath of God on Pharaoh Yul Brynner. But plagues of locusts are not just archaic tales from the crypt of history – they are very real in the year 2020. In fact, for the last three years, an enormous locust plague has been devastating crops in large parts of Africa, the Middle East, and as far as India. Up to 10% of the world’s population – as many as 760 million people – are threatened with hunger. Yemen is Ground Zero for the locust outbreak, and the US-assisted Yemeni civil war has been instrumental in unleashing this terror on the world.

Locusts have a posed a threat throughout history. They are, famously, mentioned in the Bible (most of the prophetic book of Joel is devoted to a lament for a locust plague), and Egyptian, Greek, and Roman writings all recorded apocalyptic scenes. In more modern times, locusts regularly devastated the Great Plains of the United States into the 20th century.

But what exactly is a locust? Oddly enough, no one really knew until 1920. That year, Boris Uvarov, of the British Imperial Bureau of Entomology, established that locusts were just grasshoppers that had transformed themselves from mild-mannered, solitary, green creatures into voracious, intensely social, larger-brained, black-and-yellow striped monsters. Locusts are rather like mild-mannered Bruce Banner, who is suddenly transformed into the Hulk. Banner is transformed when he gets angry; the grasshoppers are transformed when they get crowded. (The specific trigger apparently is when the back legs of one grasshopper touch another’s back legs – then they both become locusts.)

Locusts are not one species, but a group of grasshopper species that in the right climatic conditions – after heavy rainfalls and with plenty of vegetation to support dense populations – undergo their extraordinary transformation. Agglomerating in swarms that can cover up to 100 square miles, they can fly up to 124 miles per day, and in 1988 even crossed the Atlantic from Africa to South America. (Strikingly, the technical name for a group of multiple swarms of locusts is a "plague," just as a group of cows is a "herd.") In Iran, the current outbreak saw dead locusts covering the ground in a layer 6 inches high after they had been sprayed with pesticides. In their swarming phase, locusts are unbelievably voracious. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a swarm of one square kilometer can devour as much food in a single day as would be eaten by 35, 000 people.

The Desert Locust: Source of the Plague

Effectively controlling swarms became possible only in the twentieth century with the ability to spray pesticides from aircraft. Even more essential was the discovery of their breeding areas, in remote desert regions, which enabled early intervention against "hoppers,", or young locusts that hadn’t yet grown wings and had not begun to swarm. Historically, the destructiveness of locust swarms has at least been mitigated by the fact that the insects are good sources of protein and other nutrients. In fact, they’re the only halal (and kosher) insect – and people in locust-ravaged regions were more than happy to chow them down. Unfortunately, modern pest-control methods, despite their vastly greater effectiveness, have a dark side: pesticides render the locusts unsafe to eat, as the FAO has made clear.

As the locust forecasting expert for the UN’s FAO noted, Yemen – a "frontline" territory for locusts, in which they are normally endemic – had an effective locust-control system that could nip incipient swarms in the bud, but that was before the civil war broke out in 2014. But now, according to an official at the Yemeni agriculture ministry, "Our infrastructure is completely devastated…Our buildings, our vehicles, and our equipment were all destroyed and looted during the war and the government has no budget for emergencies."

Earlier in November 2019, Saudi Arabia donated $1.5 million to the FAO’s Central Region (which includes Yemen and nearby countries) to attempt to control the cascading locust activity. As the largest part of Saudi Arabia’s tiny (1% of its land mass) but critical agricultural sector is immediately adjacent to Yemen, the Saudis have a strong vested interested in managing locusts. Clearly, $1.5 million was a mere drop in the Red Sea that failed to make an impact.

A traditional, low-tech strategy was employed as the locust plague mobbed Pakistan in summer 2020. The Pakistani government urged citizens to bag sleeping locusts after dusk; as the insects hadn’t been sprayed with insecticide, they were safely ground into chicken feed. Evidently this tactic did help deal with the invasion as that country now has called an all clear.

But in Kenya, where conditions are currently ripe for swarm creation, a high-tech technique is being rolled out. This uses drones as cluster spotters, which can then spray targeted areas where swarms are beginning to build. There is much hope that this less pervasive but effective locust-control works.

As always, there’s a balancing act going on: how to judiciously respond to one of nature’s legendary agents of devastation but not destroy the human, animal, and agricultural environment. Pesticides can indeed harm the environment. But war harms it much more.

In Yemen, where war has destroyed human efforts at control, and locusts began to swarm, it looks like the end of the world. For those in the path of the swarms – whose crops, fields, and livelihoods are wiped out – it is the end of their world.

Morgan E. Hunter received her PhD in Classics from the University of California at Berkeley in 2019. She also tweeted as @Molotov_1917 as part of the award-winning #1917LIVE Twitter project that reconstructed the daily events of the Russian Revolution and the beginning of the Russian Civil War.