William L. Laurence earned the nickname "Atomic Bill" several times over. He was a Pulitzer-winning New York Times science reporter who became embedded with the Manhattan Project and followed its creation of the first atomic bombs at several sites around the United States. As the first use of the new weapon against Japan neared, seventy-five summers ago, he wrote several lengthy articles glorifying the Bomb and the men who made it, which were published, with overwhelming impact, by his newspaper (and others across the country) starting on August 7, 1945.

Then, on August 9, he observed the atomic bombing of Nagasaki from one of the support planes, another unique experience. Later he wrote about that for the Times – again, an account that required government clearance. It expressed wonderment and pride in the death-dealing device, without concern for the tens of thousands of civilians who died below. As always, Laurence provided colorful depictions of the bomb’s blast and visual effects with little focus on its startling radiation dangers.

Less well-known: Laurence continued his role as chief bomb cheerleader weeks after the Nagasaki bomb exploded.

To that point, U.S. officials had downplayed Japanese casualties in the two atomic cities and largely pooh-poohed Japanese "propaganda" claims on the lingering effects of radiation exposure and accounts of thousands perishing from some new "plague." A US general, Thomas Farrell, had toured the ruins in Hiroshima and wrongly claimed Japanese reports of at least 100,000 killed there were wildly inflated – and that only a handful died due to radiation effects.

It was the beginning of the decades-long official suppression of key evidence and falsifications, including the sabotaging – by President Truman and the military – of the first movie drama on the bomb, from MGM, the subject of my new book The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

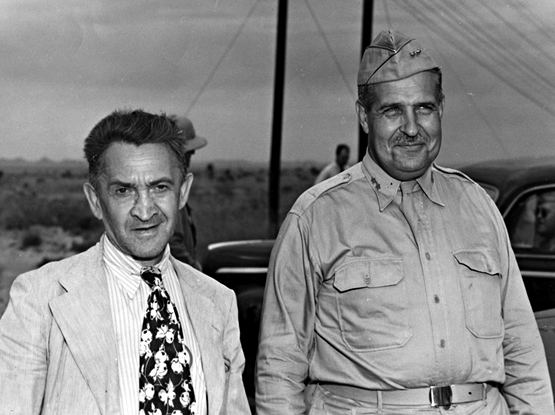

William L. Laurence and General Leslie Groves

On September 9, 1945, Laurence toured the Trinity test site, in New Mexico, where the United States tested its first atomic weapon on July 16, with General Leslie Groves and physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. The top-secret area finally had been opened to journalists.

Two weeks earlier, President Truman’s secretary, Charles G. Ross, had sent a memo to the War Department urging the military to recruit a group of reporters to explore the test site. "This might be a good thing to do in view of continuing propaganda from Japan," Ross wrote.

Now General Groves, who believed the reports of radiation disease from Japan were a “hoax,” was personally escorting some of the newsmen near ground zero. His driver, a young soldier named Patrick Stout, spent several minutes in the crater of the blast and was photographed, smiling.

Laurence’s account of this visit (delayed three days until September 12 due to a censorship review) disclosed quite frankly why he and thirty other journalists had been invited: to "give lie to" Japanese “propaganda” that ” radiations were responsible for deaths even after" the Hiroshima attack, as he wrote. He quoted General Groves calling any deaths by radiation in Japan as “very small.” (In truth, the total was probably 20,000 or more in the two bombed cities.)

General Groves had expressly asked the reporters to assist him in this effort, and they did not disappoint him. (He was also in the process of securing script approval on that MGM movie about the bomb.) Geiger counters showed that surface radiation, after nearly two months, had "dwindled to a minute quantity, safe for continuous human habitation," Laurence asserted. He did introduce one bit of contrary information: the reporters had been advised to wear canvas overshoes to protect against radiation burns.

But Laurence was keeping a lot to himself. Embedded with the Manhattan Project for months, he was the only reporter who knew about the fallout scare surrounding the Trinity test: scientists in jeeps chasing a radioactive cloud, Geiger counters clicking off the scale, a mule that became paralyzed. Here was the nation’s leading science reporter, severely compromised, not only unable but disinclined to reveal all he knew about the potential hazards of the most important scientific discovery of his time. In his report he repeatedly used the word “propaganda” to describe Japan’s claims, the debunking of reported symptoms of radiation disease, the explicit claim that the bomb had to be dropped to end the war.

The press tour, in fact, had "an oddly reassuring effect," the New York Times observed in an editorial. Still, a scientist informed the young soldier, Patrick Stout, who stood in the crater during the press tour, that he had been exposed to dangerous levels of radioactivity. Twenty-two years later Stout became ill and was diagnosed with leukemia. The military, apparently acknowledging radiation as the cause, granted him "service-connected" disability compensation. Stout died in 1969.

W.L. Laurence would win another Pulitzer for his Bomb-related reporting in 1945.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including most recently The Tunnels: Escapes Under the Berlin Wall (Crown) and The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.