For weeks, British Prime Minister Theresa May and Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson have insisted that there is “no alternative explanation” to Russian government responsibility for the poisoning of former double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury last month.

But in fact the British government is well aware that such an alternative explanation does exist. It is based on the well-documented fact that the “Novichok” nerve agent synthesized by Soviet scientist in the 1980s had been sold by the scientist–who led the development of the nerve agent– to individuals linked to Russian criminal organizations as long ago as 1994 and was used to kill a Russian banker in 1995.

The connection between the Novichok nerve agent and a previous murder linked to the murky Russian criminal underworld would account for the facts of the Salisbury poisoning far better than the official line that it was a Russian government assassination attempt.

The credibility of the May government’s attempt to blame it on Russian President Vladimir Putin has suffered because of Yulia Skripal’s relatively rapid recovery, the apparent improvement of Sergei Skripal’s condition and a medical specialist’s statement that the Skripals had exhibited no symptoms of nerve agent poisoning.

How a Crime Syndicate Got Nerve Agent

The highly independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta has published a detailed account of how Russian organized crime figures obtained nerve agent in 1994 from Leonid Rink, the head of the former Soviet government laboratory that had synthesized it.

The newspaper gleaned the information about the transaction from Rink’s court testimony in the 1995 murder of prominent banker Ivan Kivelidi, the leader of the Russian Entrepreneurs’ Round Table, an organization engaged in a conflict with a powerful group of directors of state-owned enterprises.

Rink testified that after the post-Soviet Russian economic meltdown had begun he filled each of several ampoules with 0.25 grams of nerve agent and stored it in his own garage. Just one such ampoule held enough agent to kill 100 people, according to Rink, the lead scientist in the development of the series of nerve agents called Novichok (“newcomer” in Russian).

Rink further admitted that he had then sold one of the ampoules in 1995 to Artur Talanov, who then lived in Latvia and was later seriously wounded in an attempted robbery of a cash van in Estonia, for less than $1,800.

In 1995, some of that nerve agent was applied to Kivelidi’s telephone receiver to kill him, as the court documents in the murder case reveal. Police found that there were links between Talanov and Vladimir Khutsishvili, who had been a board member of Kivelidi’s bank, according to the Kivelidi murder investigation. Khutsishivili was eventually found guilty of poisoning Kivelidi, although it was found that he hired someone else to carry out the poisoning.

But that wasn’t the only nerve agent that Rink sold to gangsters. Rink admitted in court in 2007 that he had sold four of the vials to someone named Ryabov, who had organized crime connections in 1994. Those vials were said to have been seized later by Federal Security Police.

But the investigation of the Kivelidi murder found that vials had also fallen into the hands of other criminal syndicates, including one Chechen organization. Furthermore, Rink testified that he had given each of the recipients of the nerve agent detailed instructions on how it worked and how to handle it safely.

The Mystery of the Non-Lethal Nerve Agent

The newly-revealed story of how organized crime got control of hundreds of doses of lethal nerve agent from a government laboratory sheds crucial light on the mystery of the poisoning in Salisbury, especially in light of the timeline of the Skripals on the day of the poisoning and their unexpectedly swift recovery.

Reports of their activities on March 4 show that they were strolling in central Salisbury, dining, and visiting a pub for several hours before collapsing on a park bench sometime after 4 pm.

The announcements of Yulia’s rapid recovery on March 28 and that Sergei was now “stable” and “improving rapidly” about a week later appears to be in contradiction with the British insistence that they were poisoned by a Russian government intelligence team. The Novichok-type nerve agent has been characterized as quick acting and highly lethal.

But the official Russian forensic investigation in conjunction with the Kivelidi’s murder, as reported by Novaya Gazeta, concluded that the Novichok did not take effect instantaneously but generally took from one and a half to five hours.

The Russian government has now made an official issue of the fact that the nerve agent used in the poisoning proved not to be lethal. In his news conference on April 14 Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said the Swiss Spiez Laboratory, working on the case for the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), had found traces in the Skripals’ bloodsample, of the nerve agent BZ, which was never developed by Soviet scientists but was in the arsenals of the United States and Britain.

Lavrov also acknowledged that the lab had in addition found traces of “A-234”–one of the nerve agents in the Novichok series – “in its initial state and in high concentration”. Lavrov argued that had the assassins used A-234 nerve agent, which he noted is at least eight times more deadly than VX nerve gas, it “would have killed the Skripals.”

But if the poisoning had been done with some of the A-234 nerve agent that was sold by Rink to organized crime figures, it probably would not have been that lethal.

Vil Mirzayanov, the counter-intelligence specialist on the team that developed Novichok and who later revealed the existence of the Novichok program, explained in an interview with The Guardian that, the agent lost its effectiveness. “The final product, in storage, after one year is already losing 2%, 3%,” Mirzayanov said, “The next year more, and the next year more. In 10-15 years, it’s no longer effective.”

Exposure to even a large dose of such a normally lethal poison more than 25 years after it was first produced could account for the apparent lack of normal symptoms associated with exposure to that kind of nerve agent experienced by the Skripals, as well as for their relatively speedy recovery. That lends further credibility to a possible explanation that someone with a personal grudge against Sergei Skripal carried out the poisoning.

An Absence of Nerve Agent Symptoms?

Also challenging the official British line is a statement by a medical specialist involved in the Salisbury District Hospital’s care for the Skripals revealing that they had not exhibited any symptoms of nerve agent poisoning.

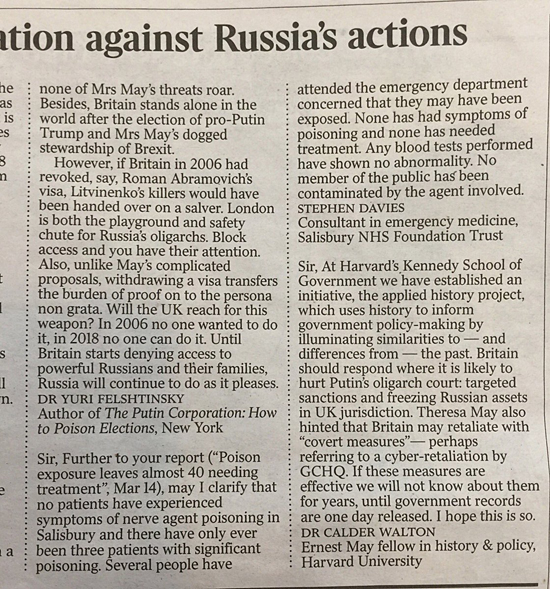

Stephen Davies, a consultant on emergency medicine for the Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust, which runs the Salisbury District Hospital, wrote a letter published in The Times on March 16 that presented a problem for the official British government position. Davies wrote,“[M]ay I clarify that no patients have experienced symptoms of nerve-agent poisoning in Salisbury, and there have only ever been three patients with significant poisoning.” Obviously, Sergei and Yulia Skripal were “patients” in the hospital and were thus included in that statement.

The Times made the unusual decision to cover the Davies letter in a news story, but tellingly failed to quote the crucial statement in the letter that “no patients have experienced symptoms of nerve-agent poisoning in Salisbury” or to report on the significance of the statement.

To rule out the possibility that Davies intended to say something quite different, this writer requested a confirmation or denial of what Davies had written in his letter from the press officer for the Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust, Patrick Butler. But Butler did not respond for a week and then refused directly to deny, confirm or explain the Davies statement.

Instead Butler said in an email, “Three people were admitted and treated as inpatients at Salisbury District Hospital for the effects of nerve agent poisoning as Stephen Davies wrote.” When he was reminded that the letter had actually said something quite different, Butler simply repeated the statement he had just sent and then added, “The Trust will not be providing any further information on this matter.”

Butler did not respond to two separate requests from the writer for assistance in contacting Davies. The refusal of the NHS Foundation Trust to engage at all on the subject underlines the sensitivity of The British government about nerve agent that didn’t work.

There are many individuals in Russia whose feelings about Sergei Skripal’s having become a double agent for Britain’s MI6 – including former colleagues of his – could provide a personal motive for the poisoning. And it is certainly plausible that those individuals could have had obtained some of the nerve agent sold by Leonid Rink that entered the black market.

Neither the British government nor the Russian government is apparently eager to acknowledge that alternative explanation. The British don’t want it discussed, because they are determined to use the Salisbury poisoning to push their anti-Russian agenda; and the Russians may be reluctant to talk about it, because it would inevitably get into details of a secret nerve agent research project that they have claimed they closed down in 1992, despite Rink’s testimony in the court case that he was still doing some work for the Russian military until 1994.

Gareth Porter, an investigative historian and journalist specializing in US national security policy, received the UK-based Gellhorn Prize for journalism for 2011 for articles on the U.S. war in Afghanistan. His new book is Manufactured Crisis: the Untold Story of the Iran Nuclear Scare. He can be contacted at porter.gareth50@gmail.com. Reprinted from Consortium News with the author’s permission.