Originally posted at TomDispatch.

What is it about the U.S. military and TomDispatch? Last August, I discovered (thanks to a correspondent in that military) that the Pentagon’s computer networks had blocked this website. (The message you received if you tried to get to it: “You have attempted to access a blocked website. Access to this website has been blocked for operational reasons by the DOD Enterprise-Level Protection System.”) And the reason/category for blocking it: “hate and racism.” As I wrote at the time, I could after a fashion understand why our work might fall under that rubric: “TomDispatch has always hated America’s never-ending, ever-spreading, refugee- and terror-producing wars that now extend from South Asia across the Middle East and deep into Africa.” And I added, “Among the authors who have spread TomDispatch’s antiwar gospel of hatred – now so judiciously cut off by the Pentagon – Nick Turse, in particular, has long grimly tracked the growth and spread of Washington’s forever wars and of the Special Operations forces, the semi-secret military that has become, in these years, their heart and soul.”

Little did I know how accurate I was, however. Today, TomDispatch regular and Managing Editor Nick Turse explains how he personally got “eliminated” from the attention of AFRICOM, the command he’s covered so assiduously for years in a way that its personnel evidently didn’t find quite flattering enough. In fact, it could be said that when it comes to criticism of American wars, this website has been eerily on target since it began in 2002. And it’s true that if you had read any of our pieces on American war making from 2004 to 2010, 2011 to the piece I posted last week, you might have felt a certain need to stop a moment and think twice about the “forever” that’s been embedded in this country’s twenty-first-century wars since they were first launched in October 2001. And that, of course, would have created obvious problems for a military intent on fighting its “infinite” conflicts to essentially the end of time.

Under the circumstances, if I had been U.S. Africa Command, which now officially plans, for example, to be in Somalia at least until 2026 (and I’m sure that no one at AFRICOM thinks of that as a real end date either), I might have “eliminated” Turse, too. But for those of you still capable of checking him out, here’s a blow-by-blow account of his adventures in AFRICOM-land. ~ Tom

AFRICOM Calls for My "Elimination" (From Their Daily Media Reports)

By Nick Turse

If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? Or to bring this thought experiment into the modern age – if it happens in the forest, does it stay in the forest? I ask this question because it has a bearing on the article to come. Specifically, what if an article of mine on the U.S. military appears somewhere in our media world and that military refuses to notice? Does it have an impact?

Before I explain, I need to shout a little: AFRICOM! AFRICOM! AFRICOM!

Any media monitoring service working for U.S. Africa Command, the umbrella organization for American military activity on the African continent, would obviously notice that outburst and provide a “clip” of this article to the command.

But just to be safe: AFRICOM! AFRICOM! AFRICOM!

Now, there is no excuse for this article not to appear in AFRICOM’S clips, which are packaged up and provided to the Africa Command’s media relations office in Stuttgart-Moehringen, Germany, on weekdays as the “AFRICOM Daily News Review.” In fact, including Africa Command or its acronym 11 times in the first 200 words of this piece must be some kind of record, the sort that should certainly earn this article the top spot in tomorrow’s review.

But no matter how often I mention AFRICOM’s name, I know perfectly well that’s not going to happen. Let me explain.

The “Elimination” of “Tom’s Dispatch”

“Like every organization that has a role in the public sphere, it is important to maintain awareness of events, incidents, and the atmospherics in order to participate tactically and strategically in the ongoing discussion,” AFRICOM’s present chief spokesman, John Manley, told me when I asked about the command’s media-tracking efforts. “We need to monitor events occurring in our AOR [area of responsibility], which is one of the most dynamic and complex regions on Earth, in order to provide the most appropriate and effective counsel for leaders to make informed decisions.”

Who could argue with that? And yet documents I obtained from AFRICOM via the Freedom of Information Act indicate that the command may never know this article even exists, even though it’s already mentioned AFRICOM 15 times.

How could that be? As a start, don’t blame some project manager at the Fairfax, Virginia-based ECS Federal, LLC (now ECS), a military contractor and “leading provider of solutions in science, engineering, and advanced technologies” hired to monitor the media and provide the command with news clips. Presumably, that person had been conscientiously taking your tax dollars in exchange for checking what outlets like the New York Times, the Washington Post, and TomDispatch had to say about AFRICOM – until, that is, U.S. Africa Command put an end to it.

Yours truly has been writing about the command for TomDispatch since 2012, as well as for The Intercept, Vice News, and Yahoo News, among other outlets. I’ve exposed a “secret war” in Libya involving more than 550 U.S. drone strikes and reported on a network of African outposts integral to such warfare. I’ve written several pieces on AFRICOM’s even larger network of outposts across the continent. I’ve covered killings and torture by U.S.-backed local forces on a drone base in Cameroon frequented by American military personnel, as well as cold-blooded executions committed by those same Cameroonian forces. I’ve written on the expansion of a drone outpost in the Horn of Africa and its role in lethal strikes against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria; on the construction of a $100-million drone base in Niger and its quarter-billion-dollar operating costs (as well as skepticism about “U.S. intentions in the region”); on a previously unreported outpost in Mali; on a hushed-up Pentagon Inspector General’s investigation into failures in the planning and carrying out of humanitarian projects; on U.S. missions in Niger, including an October 2017 ambush that killed four American soldiers; on the increasing number of U.S. special-ops missions across Africa; on special-ops activities and outposts in Libya; on a surge in the number of special-ops personnel continent-wide, as well as an even more impressive increase in the number of U.S. military activities there – and that’s just for a start.

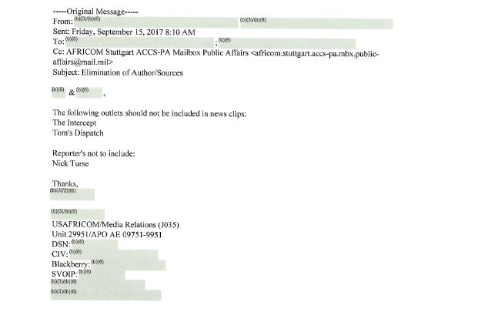

By September 15, 2017, I had already written more than 20 pieces about U.S. military activity in Africa for TomDispatch and had – just days before – revealed at the Intercept that the National Security Agency (NSA) had built a network of eavesdropping outposts in Ethiopia. AFRICOM had clearly had enough of me. At 8:10 that morning, someone at the command’s media relations office fired off an email whose subject line was, ominously enough: “Elimination of Author/Sources.” As it happened though, that act proved to have more in common with the proverbial ostrich than a drone strike. The note was, if you’ll excuse the pun, terse. It read:

The following outlets should not be included in news clips:

The Intercept

Tom’s Dispatch

Reporter’s not to include:

Nick Turse.

Thanks.

A September 2017 email from the AFRICOM Media Relations Office calling for the “elimination” of Nick Turse and “Tom’s Dispatch.”

Leaving aside that there’s no publication called “Tom’s Dispatch,” the redacted email to a program manager at ECS Federal made it clear that someone at the Africa Command’s media shop preferred not to know what I was writing about AFRICOM.

This backroom blackballing (about which I then knew nothing) would burst into the open when spokesperson Robin Mack started hanging up on me if I called the press office for information. Not long after, Lieutenant Commander Anthony Falvo, then head of AFRICOM’s public affairs branch, told me bluntly that the command was no longer going to respond to my questions. Any of them. “We don’t consider you a legitimate journalist, really,” he said and then hung up on me.

At the time that directive was written, AFRICOM’s media monitoring efforts were supposedly brand new. “The requirement began in August 2017 and was being refined over the next few months in 2017 to ensure the product met the needs of the command,” AFRICOM’s John Manley would explain once we were all talking again and I asked why I had been blacklisted. “The stories included in the ‘AFRICOM Daily News Review’ generally come from mainstream media and African local/regional press,” he added. “Because of the volume of published reports in mainstream media, we don’t typically include bloggers and others who write for niche websites and publications.”

His response left me curious, since once upon a time someone at least was looking at my pieces there. After all, a year before I was axed, an email from an AFRICOM media relations officer to fellow spokesperson Samantha Reho referenced a TomDispatch piece of mine, indicating that it was “not going in the clips.” So, in August 2016, there was evidently previous media monitoring and TomDispatch was apparently already being excluded.

AFRICOM’s anti-blog bias also seems strange for a command that once ran its own blog. Similarly, it’s odd that the Intercept was considered an unworthy niche publication when AFRICOM often provides comment to that very same outlet. Wouldn’t the command at least be interested in how its statements were being used?

Admittedly, TomDispatch has long billed itself as a “regular antidote to the mainstream media,” which may have especially rankled AFRICOM due to that command’s clear pro-mainstream bias and history of bestowing most-favored-journalist status on marquee cable news and television network journalists. I know this because in October 2017, while attempting to hang up on me, AFRICOM press office personnel accidentally put me on speakerphone, allowing me to listen in on closed-door conversations in their office for roughly an hour.

During that time, while they repeatedly ignored my calls (made from a separate line) or unceremoniously hung up on me, I listened in as they entered into embargo agreements with TV reporters, providing information on background to journalists willing to withhold news about Sergeant La David Johnson, one of the soldiers killed in an ambush in Niger that month. Such arrangements are common enough and entirely understandable when lives may be at stake. Still, I was struck by how well reporters who agreed to play ball with the press office were treated.

Of course, AFRICOM also does include “African local/regional press” outlets like Mareeg.com (an “independent news website” focused on Somalia) in its clips, but this evidently isn’t a hard-and-fast rule – at least if I’m even tangentially involved. As one ECS Federal employee wrote, “Attached is the daily media monitoring report for Thursday, 21 September 2017. Please note that we left out this piece from a Somali outlet Mareeg that was critical of AFRICOM and U.S. activities in East Africa since it was based off Nick Turse’s recent article in The Intercept” – one focused on leaked top-secret NSA documents on U.S. electronic surveillance efforts in Ethiopia.

“That’s right,” replied a contact in AFRICOM’s public affairs office, “please omit any Intercept articles, or articles based on Nick Turse’s ‘stories.’” (I must admit that I get a kick out of those scare quotes around “stories”!)

Finally, to confuse things further, I learned that AFRICOM also maintains a double standard regarding my reporting. While my articles from the Intercept and TomDispatch are verboten, those from Vice News are not. “We are aware of your stories that appear in major news organizations (i.e., your VICE story of Dec 12, 2018). Those are included,” Manley wrote me about an article on the U.S. conducting more named military operations and activities in Africa than in the Middle East. “The VICE story appeared in the December 13, 2018 edition of the Daily Media Summary. I might add it was the first story in the Executive Summary, which highlights the five or six most impactful stories of the day.”

It’s unclear, however, why its impact was significantly greater than those articles that got me banned from AFRICOM’s Daily News Review. (An impact in and of itself.) Like dozens of pieces before it, the reporting in that article laid bare much that the command had long kept secret, including that U.S. forces have suffered casualties in Cameroon, Chad, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, and Tunisia in recent years, in addition to those high-profile deaths in Niger in 2017.

Undercover Articles

Since AFRICOM generally avoids my pieces from “niche” outlets, I assume that the command has no idea that I spent an hour listening in on their press office’s mundane conversations, off-color jokes, and screaming fits back in 2017. I published that story (strike one!) at The Intercept (strike two!) just months after AFRICOM formally excised articles of mine from their daily news clips (strike three!). The command may also not know that, about a month later, another Intercept article of mine was accompanied by an audio clip of their then-media chief, Anthony Falvo, deeming me an illegitimate journalist. Then again, the first time that John Manley, AFRICOM’s current press chief, took a call from me, he asked if we were on the record and if I was recording our conversation. So perhaps word had somehow gotten to him.

Suffice it to say that AFRICOM’s press office and I are, for the moment, back on speaking terms and Manley has, in fact, been the very model of a modern military press officer: courteous, responsive, and – under the extreme limitations of his office – even helpful. It’s been something of a sea change.

Naturally, then, I briefly wondered whether, after this piece was published at TomDispatch, his attitude toward my future queries might change. Would he stop taking my calls? Hang up on me? Ignore emailed requests for answers to basic questions? Or use any of the other tactics wielded by his predecessors?

Manley’s behavior, as I said, has been commendably professional, but I suddenly realized that I had nothing to worry about anyway – unless he’s suddenly started reading TomDispatch in his off-hours. As far as I know, this website remains on AFRICOM’s blacklist, which means that this article will never appear on their radar, much less in the executive summary of their Daily News Review. While the command will answer my questions, ignorance is apparently bliss when it comes to what I write (Vice News excepted), no matter what I reveal about, or how many times I mention, AFRICOM in an article. For now, what happens at TomDispatch stays at TomDispatch – at least when it comes to Africa Command.

Nick Turse is the managing editor of TomDispatch and a contributing writer for the Intercept. His latest book is Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead: War and Survival in South Sudan. His website is NickTurse.com.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel (the second in the Splinterlands series) Frostlands, Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Copyright 2019 Nick Turse