Some of the praise being accorded the late Brent Scowcroft is deserved. As national security adviser to President George H. W. Bush, the unassuming Scowcroft was a voice for relative reason and moderation (compared to the neoconservatives who would follow him), as the USSR imploded and U.S. forces chased Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait.

But few pundits commenting on Scowcroft’s legacy are likely to raise an awkward, but important, question that haunts me. It is of such consequence that it belongs in his obituary – and his eulogy. Scowcroft knew the attack on Iraq was not only a war crime but a reflection of insane hubris. Why didn’t he join his voice to the 30 million people in 800 cities who demonstrated against the war on Feb. 15, 2003, five weeks before the invasion?

Friends Don’t Let Friends’ Sons Drive Drunk

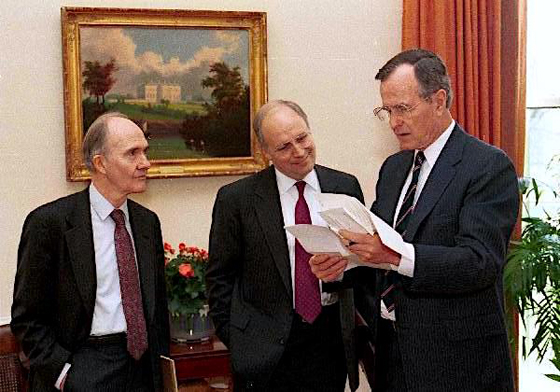

President George H. W. Bush examines papers with Sec. Dick Cheney and Gen. Brent Scowcroft in the Oval Office, April 19, 1989. (George Bush Presidential Library and Museum)

I believe Scowcroft badly served his friend George H. W. Bush on Iraq by not doing all he could to stop Bush’s son from committing a war of aggression – “the supreme international crime” as defined by the Nuremberg Tribunal.

Two years after the invasion, Scrowcroft told The New Yorker that Saddam Hussein “wasn’t really a threat. His army was weak, and the country hadn’t recovered from sanctions.” Colleagues pointed out that although Scowcroft was chairman of George W. Bush’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, he was “frozen out” of planning for Iraq, as were Bush’s secretary of state, James Baker, and others.

From the neocon viewpoint, it was essential to shut out anyone with practical, strategic, legal, or moral qualms about launching a pre-emptive war with nothing to pre-empt.

Scowcroft had had copious experience with “the crazies”, the so-called “neoconservatives.” They’d gained critical mass when Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney ran President Gerald Ford’s White House. Scowcroft had watched as Rumsfeld and Cheney maneuvered H. W. Bush into what they thought would be a dead-end job directing the CIA.

Then they sicced the crazies on Director Bush in the form of the infamous Team B, which did all it could to exaggerate the Soviet threat. I worked for DCI Bush in 1976; my colleagues and I did what we could to help him stave them off. In the end the Team B alarmists and their neocon descendants, “the crazies”, got more of a hearing than they deserved.

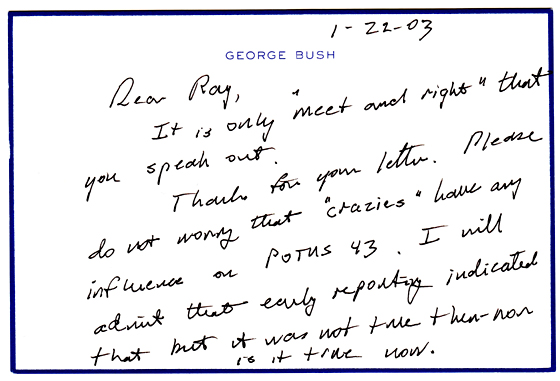

When he became vice president, I gave Bush the early morning briefings based largely on the President’s Daily Brief from 1981-85. He and I had an unusually longstanding professional and, later, cordial personal relationship. For several years after he left Washington, we stayed in touch – mostly by letter.

On Jan. 11, 2003, as the invasion of Iraq was gaining steam, I wrote him a letter asking him to speak “privately to your son George about the crazies advising him on Iraq,” adding, “I am aghast at the cavalier way in which the [Richard] Perles of the Pentagon are promoting the use of nuclear weapons as an acceptable option against Iraq.”

My letter continued:

“That such people have the President’s ear is downright scary. I think he needs to know why you exercised such care to keep such folks at arms length. (And, as you may know, they are exerting unrelenting pressure on CIA analysts to come up with the ‘right’ answers. You know how that goes!)”

His reassuring answer not to worry about any influence the “crazies” might have on his son was a big letdown.

The elder Bush may not have been fully aware of it, but he was in the dark whistling while leaving surrogates like Scowcroft and Baker the task of publicly opposing the criminal insanity of attacking and occupying Iraq. H.W. Bush may or may not have tried privately, but it was a tragedy he did not speak out publicly.

Could Scowcroft Have Stopped the Invasion?

He didn’t try very hard. There’s no doubt he saw it coming. He had to be acutely aware that writing a Wall Street Journal op-ed “Don’t Attack Saddam” on August 15, 2002 would not be enough to stop the war, even though Baker wrote a similar op-ed in The New York Times ten days later. Cheney launched the juggernaut to war the next day with a major speech greatly exaggerating the Iraqi threat. After that, resistance from Establishment figures petered out.

Scowcroft’s erstwhile protege Condoleezza Rice, the younger Bush’s national security adviser, made it abundantly clear. The New Yorker article shows how Rice for whatever reason, she had drunk what Cheney, Bush, and Rumsfeld were serving.

“Rice’s split with her former National Security Council colleagues was made evident at a dinner in early September of 2002, at 1789, a Georgetown restaurant. Scowcroft, Rice, and several people from the first Bush Administration were there. The conversation, turning to the current Administration’s impending plans for Iraq, became heated. Finally, Rice said, irritably, ‘The world is a messy place, and someone has to clean it up.’ The remark stunned the other guests. Scowcroft, as he later told friends, was flummoxed by Rice’s ‘evangelical tone.’”

That was six months before the invasion. It’s a pity that those who perceived the impending catastrophe and had the experience and credibility to shout that out, limited themselves to op-eds and head-scratching at Rice’s inanities.

Ray McGovern works with Tell the Word, a publishing arm of the ecumenical Church of the Saviour in inner-city Washington. His 27-year career as a CIA analyst includes serving as Chief of the Soviet Foreign Policy Branch and preparer/briefer of the President’s Daily Brief. He is co-founder of Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS). This originally appeared at Consortium News.