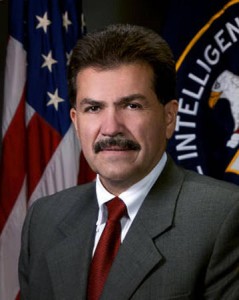

Would-be tough guys like former CIA torturer-in-chief José A. Rodriguez Jr. brag that “enhanced interrogation” of terrorists – or doing what the rest of us would call “torturing” – has made Americans safer by eliciting tidbits of information that advanced the search for al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

Rodriguez makes this case again in the Sunday’s Washington Post Outlook section in the context of the new “hunt-for-bin-Laden” movie, “Zero Dark Thirty,” though Rodriguez still disdains the word “torture.” He’s back playing the George W. Bush-era word game that waterboarding, stress positions, sleep deprivation and other calculated pain inflicted on detainees in the CIA’s custody weren’t really “torture.”

Entitled “Sorry, Hollywood. What we did wasn’t torture,” Rodriguez’s article amounts to a convoluted apologia – no, not an apology; an apologia – for torture, partly by trivializing what was done. For instance, Rodriguez explains that in the CIA’s waterboarding, “small plastic water bottles were used,” not “a large bucket,” and the detainees were strapped to “medical gurneys,” as if the size of the water-delivery system and the use of a medical device somehow make torture not torture.

Yet, while quibbling with some details of the movie and its gory depiction of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” Rodriguez largely agrees with the film’s suggestion that the harsh tactics played a key role in getting the CIA on the trail of bin Laden’s courier who eventually led Seal Team 6 to bin Laden’s hideout in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

Rodriguez writes, “I was intimately involved in setting up and administering the CIA’s ‘enhanced interrogation’ program … our program worked – but it was not torture … and enhanced interrogation techniques played a role in getting bin Laden.”

But others familiar with the chronology of events dispute that the “enhanced interrogation techniques” were responsible for any significant breaks in the case. Sens. Dianne Feinstein and Carl Levin, chairs of the Senate Intelligence Committee and the Armed Service Committee respectively, have asserted that “The original lead information had no connection to CIA detainees” and a detainee in CIA custody who did provide information on bin Laden’s courier “did so the day before he was interrogated by the CIA using their coercive interrogation techniques.”

Beyond those comments by the committee chairs, the Senate Intelligence Committee on Dec. 13 approved a long-awaited report concluding that harsh interrogation measures used by the CIA did not produce significant intelligence breakthroughs, officials have said.

The report is said to make a detailed case that subjecting detainees to “enhanced interrogation” did not help find bin Laden and often was counterproductive in the broader campaign against al-Qaeda. Feinstein called the CIA’s decisions to build a network of secret prisons and employ these harsh interrogation measures “terrible mistakes.”

The Downside of Torture

Besides the moral opprobrium that the practices brought upon the United States, the CIA’s use of torture alienated many Muslims who otherwise would have felt no sympathy for Islamic extremists. For example, U.S. military interrogators report that the vast majority of jihadists who came to fight against U.S. forces in Iraq were motivated by the disclosures about torture at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo.

FBI interrogators also have said their rapport-building techniques with an early detainee, logistics specialist Abu Zubaydah, were succeeding in eliciting important information from him before the CIA interrogators arrived and insisted on applying their brutal methods.

Author Jane Mayer in her book The Dark Side writes that the two FBI agents, Ali Soufan and Steve Gaudin, “sent back early cables describing Zubayda as revealing inside details of the [9/11] attacks on New York and Washington, including the nickname of its central planner, ‘Mukhtar,’ who was identified as Khalid Sheikh Mohammad [KSM]. …

“During this period, Zubayda also described an Al Qaeda associate whose physical description matched that of Jose Padilla. The information led to the arrest of the slow-witted American gang member in May 2002, at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago. …

“Abu Zubayda disclosed Padilla’s role accidentally, apparently. While making small talk, he described an Al Qaeda associate he said had just visited the U.S. embassy in Pakistan. That scrap was enough for authorities to find and arrest Padilla” who was suspected of plotting a “dirty bomb” attack inside the United States (although he was never charged with that offense).

In 2009, Soufan broke his personal silence on the topic in an op-ed in the New York Times, citing Zubaydah’s cooperation in providing information about Padilla and KSM before the CIA began the harsh tactics. “It is inaccurate … to say that Abu Zubaydah had been uncooperative,” Soufan wrote. “Under traditional interrogation methods, he provided us with important actionable intelligence.” [NYT, April 23, 2009]

Nevertheless, Bush administration defenders have cited the information wrested from Zubaydah — who was waterboarded at least 83 times in August 2002 — as justification for the interrogation tactics that have been widely denounced as torture.

The problem of eliciting false intelligence was demonstrated by the handling of another al-Qaeda captive, Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, who responded to threats of torture by fabricating an operational link between Saddam Hussein’s government and al-Qaeda. It was exactly the kind of information that the Bush administration had been seeking to justify its desired invasion of Iraq.

By Feb. 11, 2003, as the countdown to the U.S. invasion progressed, CIA Director George Tenet began treating al-Libi’s assertions as fact. At a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing, Tenet said Iraq “has also provided training in poisons and gases to two al-Qa’ida associates. One of these associates characterized the relationship he forged with Iraqi officials as successful.”

But the CIA’s promotion of al-Libi’s information ignored the well-founded suspicions voiced by the Defense Intelligence Agency. “He lacks specific details” about the supposed training, the DIA observed. “It is possible he does not know any further details; it is more likely this individual is intentionally misleading the debriefers.”

The DIA’s doubts proved prescient. In January 2004, al-Libi recanted his statements and claimed that he had lied because of both actual and anticipated abuse. In September 2006, the Senate Intelligence Committee criticized the CIA for accepting al-Libi’s claims as credible. “No postwar information has been found that indicates CBW training occurred and the detainee who provided the key prewar reporting about this training recanted his claims after the war,” the committee report said.

Al-Libi ended up in a Libyan prison during the period when Col. Muammar Gaddafi was cooperating with the U.S. in hunting down “terrorists.” Al-Libi “committed suicide” just two weeks after being visited in the Libyan prison by a team from Human Rights Watch in April 2009.

‘No Good Intelligence’

The al-Libi case demonstrated one of the practical risks of coercing a witness to talk. To avoid pain, people often make stuff up, an obvious point that other truth-tellers also have noted. On Sept. 6, 2006, for example, Gen. John Kimmons, then head of Army intelligence told reporters at the Pentagon, in unmistakable language:

“No good intelligence is going to come from abusive practices. I think history tells us that. I think the empirical evidence of the last five years, hard years, tells us that.”

Gen. Kimmons is a rare species – a general officer with guts, not to mention an intelligence career focusing mostly on interrogation practices. He was well aware that President George W. Bush had decided to claim publicly, just two hours later, that the “alternative set of procedures” for interrogation – methods that Bush had approved, like waterboarding – were effective.

So the real experts say one cannot acquire “good intelligence” from torture, i.e. an empirical reality upon which to base sound policy. But what about bad intelligence, especially preferred bad intelligence? If your goal in 2002 and 2003 was to make a case showing operational ties between al-Qaeda and Iraq – when none existed – well, then, torture works like a charm.

Yet, Jose Rodriguez now seeks to rewrite this sordid chapter in the CIA’s history and put his own complicity in a more favorable light.

One could say his first major move in this cover-up came in 2005 when he ordered the destruction of videotaped evidence of these “enhanced interrogation techniques.” Surely, it is easier to soft-pedal the cruel reality of waterboarding and other abusive tactics if people can’t actually see the human suffering.

And, the Washington Post, which once basked in the glory of its investigation of the Watergate cover-up, now gives generous space for a practitioner of both waterboarding and destruction of evidence to make excuses without challenge.

Just think how Official Washington’s attitude toward respect for the law has degraded over the past three decades or so. Not even President Richard Nixon dared to destroy the incriminating tapes of Watergate, even though he knew only too well that the evidence on them would be his undoing.

Yet, Rodriguez never faced criminal charges for destroying 92 videotapes recording hundreds of hours worth of CIA black-site interrogation footage. Rodriguez ordered the tapes destroyed at precisely the time when Congress and the courts were intensifying their scrutiny of the CIA interrogation program. Yet – surprise, surprise – nowhere in Sunday’s Post is there mention of that felony fact.

Indeed, as Rodriguez and his torture-friendly colleagues seek to use the occasion of the new Hollywood blockbuster to burnish their image, they are getting a helping hand from neocon newspapers like the Washington Post.

It’s reminiscent of several years ago when Tenet and other complicit figures got to go on national television and insist that “we do not torture,” as Tenet told Scott Pelley of “60 Minutes” in five consecutive sentences on May 1, 2007.

A Failed Investigation

Some will remember, too, that President Barack Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder in 2009 declared the principle that “no one is above the law” but then made very clear that some people are very much above the law, including the likes of Rodriguez.

After Holder began an investigation of torture and other war crimes, the Post ran a lead story entitled “How a Detainee Became an Asset: Sept.11 Plotter Cooperated After Waterboarding,” The article supposedly showed that waterboarding and other forms of torture worked, transforming alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammed from a “truculent enemy” into what the CIA considered its “preeminent source” on al-Qaeda.

The article declared, “this reversal occurred after Mohammed was subjected to simulated drowning and prolonged sleep deprivation, among other harsh interrogation techniques.”

The story’s sentiment dovetailed nicely with the biases of the newspaper’s top brass, forever justifying the hardnosed “realism” of the Bush administration as it approved brutal and perverse methods for stripping the “bad guys” of their clothes, their dignity, their sense of self – all to protect America.

Three weeks later, seven CIA directors – including three who were themselves implicated in planning and conducting torture and assassination – asked President Obama to put the kibosh on Holder’s investigation. CIA Director Leon Panetta, by all reports, gave them full support.

In a Sept. 18, 2009, letter to the President, the seven asked him to “reverse Attorney General Holder’s August 24 decision to re-open the criminal investigation of CIA interrogations that took place following the attacks of September 11.” Eventually, they got their way as Holder decided against proceeding with indictments. After all, everything had been properly authorized.

In his memoir, At the Center of the Storm, Tenet notes that what the CIA needed were “the right authorities,” i.e. legal permission, and a policy determination to do the bidding of President George W. Bush:

“Sure, it was a risky proposition when you looked at it from a policy maker’s point of view. We were asking for and we would be given as many authorities as CIA had ever had. Things could blow up. People, me among them, could end up spending some of the worst days of our lives justifying before congressional overseers our new freedom to act.” (p. 178)

Tenet noted that counterterrorism chief Cofer Black later told Congress, “The gloves came off” on Sept. 17, 2001, when President Bush “approved our recommendations and provided us broad authorities to engage al-Qa’ida.” (p. 208)

Presumably, it was not lost on Tenet that no lawmaker dared ask exactly what Cofer Black meant when he said, “the gloves came off.” Had they thought to ask Richard Clarke, former director of the counterterrorist operation at the White House, he could have told them what he wrote in his book, Against All Enemies.

Clarke describes a meeting in which he took part with President Bush in the White House bunker just minutes after his TV address to the nation on the evening of 9/11. When the subject of international law was raised, Clarke writes that the President responded vehemently: ”I don’t care what the international lawyers say, we are going to kick some ass.” (p. 24)

Tenet and his masters assumed, correctly, that given the mood of the times and the lack of spine among lawmakers, congressional “overseers” would relax into their post-9/11 role as congressional overlookers.

The Glorious Inquisition

On May 13, 2009, Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-South Carolina, gave an implicit hat-tip to all manner of infamous tortures past: “The Vice President [Dick Cheney] is suggesting that there was good information obtained, and I’d like the committee to get that information. Let’s have both sides of the story here. I mean, one of the reasons these techniques have survived for about 500 years is apparently they work.”

Five hundred years takes us proudly back to the Spanish Inquisition when the cardinals at least had no problem calling a spade a spade. Their term for waterboarding was tortura del agua. No euphemism like “enhanced interrogation technique” or EIT for short.

As Graham has also explained: “Who wants to be the congressman or senator holding the hearing as to whether the President should be aggressively going after terrorists? Nobody. And that’s why Congress has been AWOL in this whole area.”

The same has been largely true of news executives at the key bastions of the mainstream news media. Months into Obama’s first term, the Washington Post kept warning the young President not to mess with the tough-guys of the CIA who were just trying to keep us all safe.

To this day, the Post continues carrying water for the folks who conducted the waterboarding.

In Sunday’s article, the Post notes that the piece by Rodriguez was “written with former CIA spokesman Bill Harlow,” but again we get no help regarding Harlow’s credibility or how his readiness to mislead the American people helped clear the way for the March 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Just weeks before the invasion, Newsweek ran a story based on the text of the official U.N. debriefing of Saddam Hussein’s son-in-law Hussein Kamel when he defected in 1995. Here’s the lede of the article by John Barry on Feb. 24, 2003:

“Hussein Kamel, the highest-ranking Iraqi official ever to defect from Saddam Hussein’s inner circle, told CIA and British intelligence officers and U.N. inspectors in the summer of 1995 that after the gulf war, Iraq destroyed all its chemical and biological weapons stocks and the missiles to deliver them. Kamel … had direct knowledge of what he claimed: for 10 years he had run Iraq’s nuclear, chemical, biological and missile programs.”

In a classic understatement, Barry commented, “The defector’s tale raises questions about whether the WMD stockpiles attributed to Iraq still exist.” Barry added that Kamel had been interrogated in separate sessions by the CIA, British intelligence, and a trio from the U.N. inspection team, that Newsweek had been able to verify that the U.N. document was authentic, and that Kamel had told the same story to the CIA and the British. After all that, Barry noted the initial non-reaction from the CIA: “The CIA did not respond to a request for comment.”

Barry’s story was, of course, completely accurate. And it was about something the CIA in 2003 knew with 100 percent certainty – i.e., what Hussein Kamel had said in 1995. So what happened to this story? Remember, Newsweek had the transcript of Kamel’s debriefing and had done its homework in checking the story out.

The CIA issued a strong denial of the story. Spokesman Bill Harlow stated: “It is incorrect, bogus, wrong, untrue.” And the rest of the mainstream media said, in effect, “Oh, Gosh. Thanks for letting us know. We might have run something on it.”

Aren’t you glad that newspapers like the Washington Post still give folks like Rodriguez and Harlow prominent space to tell their lies?

Ray McGovern works with Tell the Word, a publishing arm of the ecumenical Church of the Saviour in inner-city Washington. He was an Army Infantry/Intelligence officer in the early 60s and then served in CIA’s analysis division for 27 years.

This article was originally published at Consortium News.