The Quest for Gaza’s Energy, Part 1

As the Second Intifada was about to begin in September 2000, PLO leader Yassir Arafat celebrated a natural gas discovery in a fishing vessel about 30 kilometers off the Gaza Strip. “This will provide a solid foundation for our economy, for establishing an independent state with holy Jerusalem as its capital,” Arafat said.

Efforts to undermine this hope that could have done much to foster the Gazan economy have gone in tandem with the crumbling of the peace process.

Gaza catastrophe is (also? mainly?) about natural gas

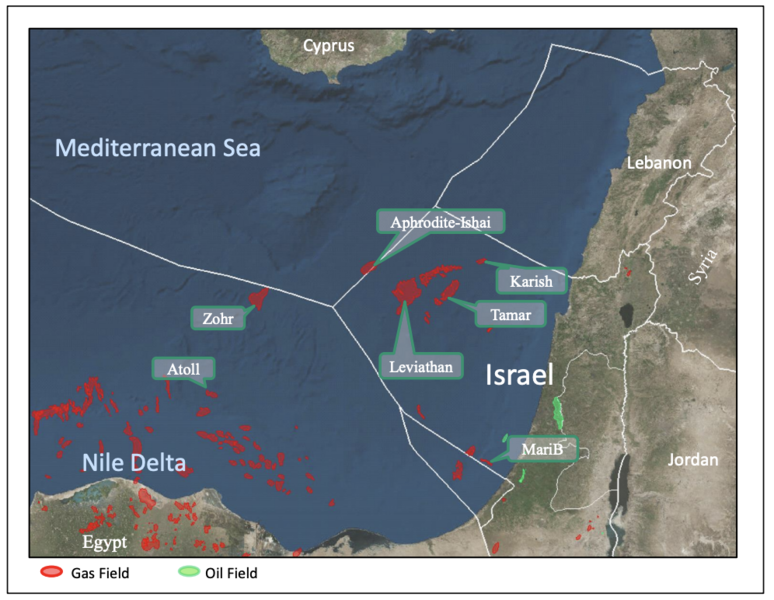

Ever since the late 1990s, the Eastern Mediterranean has become highly attractive to energy interests, with major fields like Israel’s Leviathan (600 billion cubic meters, bcm), Egypt’s Zohr (850 bcm), and the Gaza Marine field (28–30 bcm).

Relative to Israel’s Leviathan, which generates $10 billion annually in export revenue, or Egypt’s Zohr field, which meets 40% of Egypt’s gas demand, the Gaza Marine field has lower output. However, it could have a transformative impact on Gaza’s economy and Palestinian living standards.

Located 30 km offshore from the Strip, the Gaza Marine field was discovered in 2000 by British BG and the Palestinian Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC). It was expected to develop revenue at $4 billion.

Let’s put things into context: In 2023, Gaza’s GDP amounted to less than $18 billion. And today, after Israeli decimation, it is barely $350 million. So the field represents a lifeline to Gazans and a great opportunity to overcome chronic energy shortages in Gaza, which remains highly dependent on foreign aid.

With its natural gas industry, Egypt was to serve as the onshore hub and transit point for the gas. The British BG Group was to finance the development and operations in return for 90 percent of the revenues. The Palestinian Authority (PA) would receive just 10 percent, plus access to adequate gas to meet their needs.

Israel’s cut

It was a colonial-style “profit-sharing” deal. But Israel, too, wanted a cut. In 1999, PM Ehud Barak deployed the Israeli navy in Gaza’s waters to impede the PA-BG deal. Israel demanded the gas to be piped to its facilities at a below-market-level price and control of the revenues fated for Palestinians, ostensibly to prevent the monies from being used to “fund terror.”

In 2005, when Israeli PM Ariel Sharon was focused on “disengagement” from Gaza, BG signed a memo with the EGAS (Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company) to sell the gas there. But that deal was subsequently foiled, when British PM Tony Blair intervened at the last minute to plead the Israeli government’s case to BG, allegedly following a request from Ehud Olmert, Sharon’s successor as PM.

In the new deal structure, the gas would be delivered to Israel, not Egypt, and the funds would first be channeled to the Federal Reserve Bank in New York for future distribution, ostensibly to preempt “financing of terrorist attacks.”

Unsurprisingly, BG was a major client of JP Morgan, the US financial giant that subsequently paid Blair millions of dollars as a senior adviser. (That’s why Blair is now back in Gaza where he senses even bigger opportunities.)

These ploys killed the prospects for a limited Palestinian budget autonomy and the Oslo Accords, while a path was paved for new wars, which would then be blamed on the Palestinians. When the Hamas-led Palestinian unity government refused the impossible offer, Israeli PM Ehud Olmert imposed a blockade on Gaza. The economic warfare was hoped to lead to a political crisis and an uprising against Hamas.

Gaza’s offshore gas reserves

The 2008-2009 War did cause devastation in Gaza but failed to transfer the control of the gas fields to Israel. So, as the West was swept by the financial crisis of 2008, the Netanyahu government found itself also struggling with an energy crisis.

Amid the Arab Spring in the region, Israel lost 40% of its gas supplies and was hit by soaring energy prices, which triggered the 2011 cost-of-living mass protests in Israel, the largest in decades. By the same token, the domestic turmoil gave Netanyahu cabinets a compelling motive to seek energy sovereignty in Gaza.

Cost-of-living protest in Tel Aviv in August 2011

Ironically, Netanyahu’s government was saved by the discovery of a huge field of recoverable natural gas in the Levantine Basin. The Tamar and Leviathan fields were manna from heaven to Netanyahu. However, Israel claimed “most” of the newly confirmed gas reserves lay within its territory, which led to increasing tensions with Lebanon, Syria, Cyprus, and the Palestinians.

To ease tensions, the U.S. pioneered its “gas diplomacy,” hoping to use the region’s new energy wealth to bring countries in conflict back to the negotiating table.

Levantine Basin gas and oil

But even before October 7, the gas diplomacy visions proved inflated. Though discovered years before Israel’s Tamar and Leviathan, the offshore Gaza Marine gas field “remains inaccessible due to Israeli restrictions, and thus offers no relief to the people in Gaza suffering under a stifling Israeli siege.”

In theory, the timing was favorable, due to the high energy prices and Europe’s need to diversify gas resources. Yet, the Levantine gas ecosystem lacked pipelines out of the sub-region, remained dependent on limited gas liquefaction capabilities in Egypt. So, progress was frustratingly slow.

In addition to energy discoveries, there was still more at stake: an alternative distribution canal that ran right next to Gaza – in Israel.

An Israeli alternative to the Suez Canal

Some 12 percent of the world’s trade passes through the Suez Canal, which connects the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez with the Mediterranean Sea. That translates to $9.4 billion in annual revenues to Egypt. But the traffic hasn’t always been smooth.

In March 2021, the Canal was blocked for six days by a container ship that had run aground. The closure required oil tankers to divert around the Cape of Good Hope near the southern tip of Africa, adding over 4,000 kilometers to the transit from Saudi Arabia to the United States.

Today, the Suez Canal is operational, but traffic remains significantly lower than normal due to the Red Sea crisis and related security concerns. And so it was that amid the Gaza War, media buzz intensified about an Israeli canal initiative. But it wasn’t a new idea.

In the ancient era, there were a number of famous routes passing through the Negev desert. The city of Eilat functioned as a key port during the reign of Solomon, as the trading point with Africa and the Orient.

In the mid-19th century, British Rear-Admiral William Allen had championed construction of a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, as an alternative to the proposed Suez Canal. But as Allen failed to rally the powers-to-be behind his dream plan, the Suez Canal was built. It reduced the journey from London to the Arabian Sea by some 8,900 kilometers.

Yet, the dream of an alternative to the Suez Canal retained its position in the early Zionist visions. In his novel The Old-New Land (1902), Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, saw the Jewish land as a nodal point between two massive regional blocs and envisioned a future when “traffic between Europe and Asia had taken a new route – via Palestine.”

It was this idea that PM Netanyahu was alluding to with his map of the “new Middle East” in the UN General Assembly just two weeks before the Hamas offensive of October 7, 2023. With Palestine and Palestinians effectively erased from the map, the debacle caused an international firestorm. Yet, just two years later, some 90 percent of Gaza has been destroyed and the West Bank is haunted almost daily by violent pogroms.

The plan of 520 two-megaton nuclear explosions

In the 1950s, Israel had a deep-water port constructed at Eilat, while a modern port was built on the southern coast of the Mediterranean at Ashdod, just 60 kilometers from the Gaza border.

In the 1960s, the Suez Canal had also become vital to U.S. interests, as evidenced by a plan of the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory (LLL) that was declassified only at the end of the Cold War. One proposed project built on a memorandum by H.D. MacCabee, advocating the use of 520 2-megaton nuclear explosions to excavate a canal through the Negev Desert.

In 1970, the Israeli shipping line ZIM set up a subsidiary to provide service for cargoes transported cross-country between Ashdod and Eilat, while construction started on a 42-inch oil pipeline through Negev from Eilat to Ashkelon, just 12 kilometers from the Gaza Strip.

These visions leaped ahead in October 2020, when the Israeli state-owned Europe Asia Pipeline Company (EAPC) and the UAE-based MED-RED Land Bridge inked a deal to use the Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline to move oil from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean; just 1 month after the Abraham Accords.

The Ben Gurion Canal Project

In April 2021, Israel announced that the Ben Gurion Canal would connect to the Mediterranean Sea by getting around the Gaza Strip. Unlike the Suez Canal, the Israeli dual-canal would handle ships going in both directions. It would be almost one-third longer than the 193 km Suez Canal.

The costs of the 5-year project would amount to $16-$55 billion. The canal was projected to generate $6 billion or more in annual income.

Obviously, whoever controls the proposed canal would have enormous economic influence (and political leverage) over the global supply routes for commodities shipping.

Before October 7, the only thing that stood between the Netanyahu government and the massive canal project was a Palestinian Gaza and Hamas. The challenge was to get rid of both.

The author of The Obliteration Doctrine (2025) and The Fall of Israel (2024), Dr Dan Steinbock, a visionary of the multipolar world, is the founder of Difference Group and has served at the India, China and America Institute (US), Shanghai Institute for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net/

The original version of this series of commentaries was published by the Informed Comment (US) in two parts on October 16 and 17, 2025.