The TV series, The Vietnam War, is absolutely riveting. The ten discs in the DVD set provide over 17 hours of viewing, and there is hardly a moment wasted. It is evenhanded to the most admirable degree, and presents the points of view of war-supporters in the US and Vietnam as well as doubters, protesters and those who now bitterly regret the years of hellish slaughter. (To declare an interest: I served there in the Australian army in 1970-71 although, as a staff officer, did not see combat.) The producers and presenters of this masterpiece are to be congratulated, as are the US Public Broadcasting Service and those who contributed the 30 million dollars it took to make it.

Being balanced and admirably impartial, there is no leitmotif as such, no recurrent theme that might guide us to move to a particular stand, because, in the words of one reviewer, it “carries with it a sense of trustworthiness; of a project undertaken with humility, but without an agenda beyond the truth.”

Yet there is one particular feature of the war that does recur: the bombing. The ceaseless, pounding, massively destructive, relentlessly thundering bombing, rocketing and napalming in north and south Vietnam – and also in bordering Laos and Cambodia.

In Laos alone the US flew 580,344 bombing missions, dropping 2.5 million tons of munitions, or seven bombs for every man, woman and child in the country, “a planeload of bombs being unloaded every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years.” When President Obama visited Laos in 2016 he acknowledged it as the most heavily bombed nation in history and accepted that “the United States has a moral obligation to help Laos heal.” I doubt that Mr. Trump will endorse such sentiments about Laos or any other country.

A 2016 analysis of the bombing of South Vietnam showed that the campaign not only failed to further US war aims but in many ways adversely affected them, and concluded that “While US intervention aimed to build a strong non-communist state in South Vietnam, the study documents that bombing instead weakened local government and noncommunist civic society.” Further, villages “targeted with bombing exhibited less trust of Americans and South Vietnamese authorities, and more trust of North Vietnamese soldiers and local insurgents. Such areas also suffered from greater economic problems, less civil society, and less effective local governance.”

In a wonderful example of unintentional irony, the US Defense Secretary, General James Mattis, arrived in Vietnam for a two-day visit on January 24 – the very day we were told that air strikes in Afghanistan are going to intensify. US Air Force Major General James Hecker, commander of 9th Air and Space Expeditionary Task Force-Afghanistan and NATO Air Command-Afghanistan said “the Taliban still has not felt the full brunt of American and Afghan air power. With the arrival of new air assets and the growing capabilities of Afghan pilots, the Taliban will have a constant eye towards the sky as an integrated unified fight is aimed directly to them.” But the eyes of the Taliban are focused closer to the ground, where they conduct barbaric and most effective attacks.

General Hecker’s statement came four days after a terrorist assault on a luxury hotel in Afghanistan’s capital in which about forty people were killed. The US Embassy had warned that “We are aware of reports that extremist groups may be planning an attack against hotels in Kabul” but, as CNN observed, “what we learn most clearly from this attack is that despite the clarity of the warning and the fact there are only a handful of major hotels in Kabul that could have been the target, the attack couldn't be prevented.” It is open to question if any planned attacks will in future be prevented by General Hecker’s full brunt of air power.

On January 19, the day before the hotel carnage, as part of General Hecker’s war-winning air strike capability, a squadron of A-10 ground attack aircraft arrived in Afghanistan and the US-NATO media release noted that “Commonly known as the Warthog, the A-10’s return to Afghanistan supports the increased need for close air support and precision strike capacity . . . including the strategic air campaign targeting Taliban revenue sources and counter-terrorism operations that continue to take place.” This strategic air campaign is intended to “implement the US South Asia Policy under Operation Freedom’s Sentinel.”

Freedom’s Sentinel is separate from the US-NATO Resolute Support mission, which provides “further training, advice and assistance for Afghan security forces and institutions” and has no combat role. On the other hand, Freedom’s Sentinel has four or five or maybe six thousand special forces soldiers (the Pentagon does not know exactly how many of its troops are deployed around the world), whose Mission is to conduct “counterterrorism operations against al Qaeda, its associates in Afghanistan, and the Islamic State…”

These special forces are supported by vast airpower including dozens of F-16s and seaborne F-18s as well as strategic B-52 bombers (as used to bomb Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia) of the 69th Expeditionary Bomber Squadron, in addition to F-22 Raptors, which are “a leap in warfighting capabilities for the US Air Force and coalition forces . . .” Each Raptor costs 250 million dollars and has technical capabilities that appear to be slightly more advanced than are required to combat an enemy of ragtag insurgents who do not possess aircraft or radars and whose most advanced antiaircraft weapon is a light machine gun.

Raptors were tasked to bomb Afghanistan because they supposedly aim their bombs more accurately than other aircraft, and that may be desired because of the number of civilian casualties caused by US airstrikes in 2017. The UN reported that in January-September at least 205 civilians were killed and 261 wounded in such attacks. More than two thirds of the victims were women and children.

Unsurprisingly a member of the Afghan parliament said that “Using more bombs and bigger bombs also creates hatred as it causes more civilian deaths,” which, as in Vietnam, sums up the effects of intensified bombing.

Six months ago President Trump announced his new strategy for the war in Afghanistan. He declared that “in the end, we will win” but didn’t specify what “winning” entailed, although he said that on the way to that desirable outcome “we are killing terrorists” who “need to know they have nowhere to hide, that no place is beyond the reach of American might and American arms. Retribution will be fast and powerful.” But has it been fast and powerful? How do you administer retribution to a dead suicide bomber? Maybe you can blast the particular person who supplied the explosives, but there are lots more suppliers and bombers out there.

On January 27 terrorists struck yet again, killing 103 people and injuring another 230 when a suicide bomber’s vehicle, supposedly an ambulance, exploded in Kabul city center.

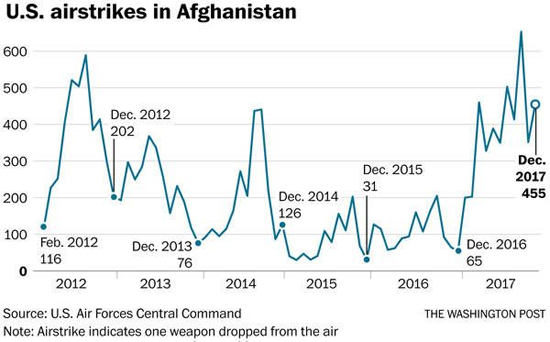

In the first year of the Trump presidency, US airstrikes in Afghanistan reached the highest level since 2012.

Concurrently, terrorist attacks in Kabul increased in numbers and savagery. In 2017 thirty people were killed in March in an attack on a hospital; in May a truck bomb killed 150; in June three bombs killed fifteen and in December a bomb at a cultural center killed fifty. So far in 2018, in addition to the hotel slaughter and the ambulance suicide bombing, twenty were killed by a suicide bomber on January 6.

Do Mr. Trump and his intellectual generals believe their bombing surge will improve the domestic security of Afghanistan? They should reflect on their airstrike of August 10 last year which this report described in harrowing detail:

As US warplanes flew above a cluster of villages where Islamic State militants were holed up in eastern Afghanistan, 11 people piled into a truck and drove off along an empty dirt track to escape what they feared was imminent bombing. They did not get far.

An explosion blasted the white Suzuki truck off the road, opening a large crater in the earth and flipping the vehicle on its side in a ditch. A teenage girl survived. The 10 dead included three children, one an infant in his mother’s arms.

The lone survivor of the August 10 blast in Nangarhar province, and Afghan officials who visited the site, said the truck was hit by an American airstrike shortly before 5 pm. Relatives expressed horror that US ground forces and surveillance aircraft could have mistaken the passengers, who included women and children riding in the open truck bed – in daylight with no buildings or other vehicles around – for Islamic State fighters.

“How could they not see there were women and children in the truck?” said Zafar Khan, 23, who lost six family members, including his mother and three siblings, in the blast.

In a statement after the incident, the US military acknowledged carrying out a strike but said it killed militants who ‘were observed loading weapons into a vehicle’ and ‘there was zero chance of civilian casualties’.

Let us reflect on the fact that “by the time the last American combat troops left Vietnam in 1973, the US had dropped some 4.6 million tons of bombs, destroying a large percentage of the nation’s towns and villages and killing an estimated 2 million Vietnamese people.” And the US lost the war. Bombing isn’t going to win the war in Afghanistan, either, and it is deceitful and morally indefensible to claim that it will.

In March 2013 Trump tweeted “we should leave Afghanistan immediately” and nine months later urged Americans not to “allow our very stupid leaders to sign a deal that keeps us in Afghanistan through 2024 – with all costs by U.S.A. MAKE AMERICA GREAT!”

After the ambulance bombing a Kabul shopkeeper said “How are we to live? Where should we go? We have no security: we don’t have a proper government, what should we do?”

Who is the stupid leader, now?

Brian Cloughley is author of A History of the Pakistan Army. This originally appeared at Strategic Culture Foundation.