Just imagine: You run a flagship national newspaper, the New York Times. It’s the fifth anniversary of President Bush’s catastrophic invasion of Iraq. Your own record of reportage in the period leading up to the invasion was not exactly sterling. So, for a change of pace, you decide to turn most of your double op-ed page in your Sunday “Week in Review” over to people who can look back thoughtfully on the misapprehensions of that moment.

But who? Now, that’s a tough one. You want “nine experts on military and foreign affairs” who can consider “the one aspect of the war that most surprised them or that they wished they had considered in the prewar debate.” Hmm, sounds like an interesting idea. Of course, one option would be to gather together an involved crew who, even before the invasion began, saw in one way or another that problems, possibly disaster, lay ahead. That would be a logical thought…

…But it wouldn’t be the Times, which this past Sunday chose to ask a rogue’s gallery of “experts” who led (or cheer-led) us deep into the war and occupation what surprised them most. Leading off those pages were Richard Perle, nicknamed “the Prince of Darkness”; L. Paul Bremer III, the former American viceroy of Baghdad, who so brilliantly disbanded the Iraqi army and much of the country as well; not to speak of invasion and occupation cheerleaders Frederick Kagan, Danielle Pletka, and Kenneth M. Pollack. With the exception of Pollack, all of them unsurprisingly pointed the finger elsewhere or claimed they were really on the mark all along.

So, just in case the Times has a sudden, bizarre urge on some future anniversary to ask a cast of characters who didn’t drive us into the nearest ditch to look back, it seems worthwhile to start on a list of suggestions for its editors. And that’s where Greg Mitchell, the editor of Editor & Publisher magazine, comes in.

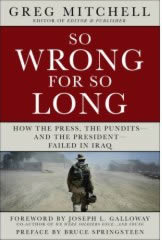

He himself is a shining example of someone who exhibited foresight about the invasion and then regularly dealt with issues that the mainstream media was slow to pick up. Just take, for example, this initial sentence he wrote on March 7, 2003, less than two weeks before Bush’s invasion began, for a piece included in his new book, So Wrong for So Long: How the Press, The Pundits – and the President – Failed on Iraq: “Considering that we seem to be on the verge of a major war, with little firm evidence of the Iraqi WMD driving it, the questions for Bush at his final press conference before the war seems likely to start were relatively tame.” Mitchell then asked 11 questions of his own, all more piercing than any posed on Sunday’s Times op-ed page five years later.

He himself is a shining example of someone who exhibited foresight about the invasion and then regularly dealt with issues that the mainstream media was slow to pick up. Just take, for example, this initial sentence he wrote on March 7, 2003, less than two weeks before Bush’s invasion began, for a piece included in his new book, So Wrong for So Long: How the Press, The Pundits – and the President – Failed on Iraq: “Considering that we seem to be on the verge of a major war, with little firm evidence of the Iraqi WMD driving it, the questions for Bush at his final press conference before the war seems likely to start were relatively tame.” Mitchell then asked 11 questions of his own, all more piercing than any posed on Sunday’s Times op-ed page five years later.

As his book makes brilliantly evident, you didn’t have to be wrong all the time to be an “expert” on Iraq. His article below begins the necessary acknowledgment of those who were right, or did right, in these years and it should encourage all of us to make our own lists and create our own walls of honor to go with the wall of shame the Times displayed Sunday.

My list would be long indeed, but it would certainly include: the Knight Ridder (now McClatchy) reporters Warren Stroebel and Jonathan Landy in Washington, as well as Tom Lasseter, Hannah Allam, and others in Iraq who never had a flagship paper to show off their work, but generally did far better reporting than the flagship papers; Seymour Hersh, who simply picked up where he left off in the Vietnam era (though this time for the New Yorker); Riverbend, the young Baghdad blogger who gave us a more vivid view of the occupation than any you could ordinarily find in the mainstream media (and who has not been heard from since she arrived in Syria as a refugee in October 2007); Jim Lobe, who covered the neocons like a blanket for Inter Press Service; independents Nir Rosen and Dahr Jamail, as well as Patrick Cockburn of the British Independent, who has been perhaps the most courageous (or foolhardy) Western reporter in Iraq, invariably bringing back news that others didn’t have; the New York Review of Books, which stepped into some of the empty print space where the mainstream media should have been (with writers like Mark Danner and Michael Massing) and was the first to put into print in this country the Downing Street Memo, in itself a striking measure of mainstream failure; and Juan Cole, whose Informed Comment Web site was so on the mark on Iraq that reporters locked inside the Green Zone in Baghdad read it just to keep informed.

Maybe I’d throw in as well all the millions of non-experts who marched globally before the war began because commonsense and a reasonable assessment of the Bush administration told them a disaster – moral, political, economic, and military – of the first order was in the offing. And, of course, that’s just a start. Tom

Unsung Heroes and Alternate Voices

Some of the best of five years of Iraq war coverage

by Greg Mitchell

In the five years since the tragic U.S. intervention in Iraq began, many journalists for mainstream news outlets have certainly contributed tough and honest reporting. Too often, however, their efforts have either fallen short or been negated by a cascade of pro-war views expressed by pundits, analysts, and editorial writers at their own newspapers or broadcast/cable networks. This sorry record is detailed in my new book, So Wrong for So Long: How the Press, the Pundits – and the President – Failed on Iraq.

But allow me – for once – to focus on the positive by suggesting that many of the most critical and important journalistic voices exposing the criminal nature of, and the many costs of, this war have emerged from an “alternative” universe that includes former war correspondents, reporters for small newspapers or news services, comedians, aging rock ‘n rollers, and bloggers, among others.

We can all name our favorite not-famous reporters or online scribes who have covered the war in Iraq in ways that should have been far more common, or offered biting commentary here at home. A full list would be long indeed, but here, on the fifth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq, is my modest tip of the hat to just a few of my own favorites, based on what, to some, might seem an idiosyncratic definition of “journalist”:

Chris Hedges: Looking back at my extensive, and often critical, commentary on media coverage of the Iraq war over the past five years, I’m struck yet again by the way Chris Hedges stands out as a kind of prophet. The former New York Times war reporter, who is now affiliated with the Nation magazine and other “outsider” venues, was among the few who recognized from the start that taking Baghdad would be the easy part.

We interviewed him at Editor & Publisher (E&P) magazine, where I have long been editor, three times just before and after the war was launched. Speaking of the coming occupation of Iraq in April 2003, for example, he said: “It reminds me of what happened to the Israelis after taking over Gaza, moving among hostile populations. It’s 1967, and we’ve just become Israel.”

About a month into the occupation, in May 2003, he explained: “We didn’t ever discover how many civilian casualties occurred in the first Gulf War, and I doubt we’ll ever know about this one.” He then added: “We don’t have a sense of what we have waded into here. The deep divisions among the varying factions could be extremely hard to bridge, and the historical and cultural roots are probably beyond the American understanding. … For occupation troops, everyone becomes the enemy…

“My suspicion is that the Iraqis view it as an invasion and occupation, not a liberation. This resistance we are seeing may in fact just be the beginning of organized resistance, not the death throes of Saddam’s Fedayeen.”

Mark Benjamin: He now writes tough pieces for Salon.com, but his vital early exposure of hidden damage to – and mistreatment of – our troops in Iraq in 2003-4, came when he worked for a well-known news service that these days might just as well be considered “underground” for all the influence it wields: United Press International.

In October 2003, for starters, he revealed that hundreds of soldiers at Fort Stewart, Ga., were being kept in hot cement barracks without running water while they waited, for months at a time in some cases, for medical care. (Twelve days later he exposed ghastly conditions at Fort Knox in Kentucky.) The stories produced quick and measurable results rather than mere promises. Army Secretary Les Brownlee flew to Fort Stewart; new doctors were dispatched; and, within a month, the barracks had been closed. Pentagon officials later declared that they would spend $77 million the following year to help returning troops get better treatment.

And the media started paying more attention to the injured. The 2,000 non-fatal casualties to that moment had rarely been highlighted until Benjamin went to work.

He was also one of the first reporters to link illnesses and deaths among American troops in Iraq (and elsewhere) to the possible side effects of various vaccines being administered by the Pentagon. In addition, in 2003 and 2004, he was the first journalist to analyze closely and repeatedly non-combat injuries and ailments in Iraq – a step E&P had advocated as early as July 2003. Benjamin showed that one in five medical evacuations from Iraq were for neurological or psychiatric reasons. He followed that with a probe of the unnervingly high suicide rate among soldiers in Iraq and also revealed that two returning soldiers had killed themselves at Walter Reed Medical Center in Washington (a fact the military had kept hidden). Only later did these issues finally gain a wider airing in mainstream newspapers.

Lee Pitts: Everyone remembers the uproar caused when, in early December 2004, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld admitted that vehicles carrying our soldiers in Iraq were poorly armored – and his famous quote about going to war with the Army you have, not the one you want. But did you know that the whole incident was sparked by a reporter for a local Tennessee paper?

Lee Pitts of the Chattanooga Times, embedded with a military unit based near that city, had learned in early December 2004 that Rumsfeld was slated to appear at a “town hall” gathering in Kuwait at which only soldiers would be allowed to ask questions. Already aware that the troops were angry about the lack of protection offered by their largely unarmored vehicles – they were finding scrap metal and adding their own ad hoc armor to their trucks and Humvees – he made sure Rumsfeld was challenged by arranging for a couple of soldiers whom he knew to be in a critical mood to get a chance at the microphone.

Specialist Thomas Wilson, a scout with the Tennessee National Guard, asked the key question at the gathering. (His picture would appear on the front page of the New York Times.) Pitts had previously written two stories about the lack of armored vehicles in Iraq to little effect and now, as he related in an e-mail, “it felt good to hand it off to the national press. … The soldier who asked the question said he felt good b/c he took his complaints to the top. When he got back to his unit most of the guys patted him on the back but a few of the officers were upset b/c they thought it would make them look bad.”

Then, in an understatement, he added: “From what I understand this is all over the news back home.”

Stephen Colbert: When he was still with The Daily Show, Stephen Colbert noted that the growing American unease as the Iraq war started to drag on was all Saddam Hussein’s fault – for not having those weapons of mass destruction. Well, finding WMD would have gotten the media off the hook, at least, for its worst failures in the prewar period – besides helping Bush’s approval ratings.

Colbert, as usual, hit the nail on the head. It’s surely a sign of our times that many critics of the war will point to that faux-pundit as one of the true heroes among all the leading TV “newsmen.”

Many fondly recall the Comedy Central star’s in-his-face mockery of President Bush at the White House Correspondents Association dinner in Washington, D.C., in April 2006. But who remembers that he was just as critical of journalism’s Beltway boys (and girls) in the audience?

Here is the key passage: “Let’s review the rules. Here’s how it works. The president makes decisions, he’s the decider. The press secretary announces those decisions, and you people of the press type those decisions down. Make, announce, type. Put them through a spell check and go home. Get to know your family again. Make love to your wife. Write that novel you got kicking around in your head. You know, the one about the intrepid Washington reporter with the courage to stand up to the administration. You know – fiction.”

Neil Young: Rock star as journo? It essentially happened in 2006 when Neil Young, son of a famous Canadian sportswriter, hurriedly wrote and released (only online at first) his ripped-from-the headlines Living With War CD. He even proposed impeaching the president “for lying” (and “for spying”). In one of the songs in the collection, Young sang repeatedly: “Don’t need no more lies.”

He emphasized the prohibition against the media showing pictures of coffins with the American dead being returned from Iraq, singing: “Thousands of bodies in the ground/Brought home in boxes to a trumpet’s sound/No one sees them coming home that way/Thousands buried in the ground.” In another song: “More boxes covered in flags/ but I can’t see them on TV.”

When Young urged that Americans “Impeach the President,” he included audio clips of embarrassing Bush statements (“We’ll smoke them out…”). But a highlight of the collection was the blistering “Shock and Awe,” which, along with its antiwar lyrics, included the more philosophical, “History is a cruel judge of overconfidence.” He also recalled that “back in the days of Mission Accomplished … the sun was setting on another photo op.”

McClatchy Baghdad Bloggers: With danger and violence in Baghdad keeping most Western reporters from venturing far outside the heavily fortified Green Zone, the U.S. media came to rely ever more heavily on Iraqi staffers and correspondents. More than a year ago, the McClatchy bureau in Baghdad launched a blog, Inside Iraq, written only by those Iraqis and, ever since, it’s provided some of the most valuable and brutally honest views of the war to be found anywhere.

The bureau’s bloggers exposed the horrid impact of the war simply by writing about their own lives: their grueling experiences getting to and from work, dealing with a lack of electricity and fuel, caring for wounded or grieving family members. At the end of 2007, six of the Iraqi women who worked in the bureau received the International Women’s Media Foundation Courage in Journalism Award.

In introducing the six McClatchy reporters – Shatha al-Awsy, Zaineb Obeid, Huda Ahmed, Ban Adil Sarhan, Alaa Majeed, and Sahar Issa – at a dinner in New York, Bob Woodruff of ABC News said: “These six Iraqi women have reported the war in Baghdad from inside their hearts. They have watched as the war touched the lives of their neighbors and friends, and then they bore witness as it reached into the lives of each and every one of them.”

“All the while, they have been the backbone of the McClatchy bureau, sleeping with bulletproof vests and helmets by their beds at night, taking different routes to work each day, trying to keep their employment by a Western news organization secret,” said Woodruff, who himself was grievously wounded while covering the war in Iraq. “All have lost family members or close friends,” he continued. “All have had their lives threatened. All have had narrow escapes with death.”

According to David Westphal, McClatchy’s Washington Editor: “Only the handful of you who have worked in Baghdad can fully glimpse what it means to be an Iraqi journalist working for an American news organization. The rest of us can only stand in awe, and express our thanks for all they have given, and risked, to tell the story of their country.” Amen.

That’s a selection from my “best of” list. What about yours?

Greg Mitchell is the editor of Editor & Publisher magazine, which has won several major awards for its coverage of Iraq and the media. His new book is So Wrong for So Long: How the Press, the Pundits – and the President – Failed on Iraq (Union Square Press). He has written seven previous books on media, history, and politics including Tricky Dick and the Pink Lady and The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair’s Race for Governor of California and the Birth of Media Politics (winner of the Goldsmith Book Prize). He also co-authored, with Robert Jay Lifton, Hiroshima in America. He blogs at Pressing Issues.

Copyright 2008 Greg Mitchell