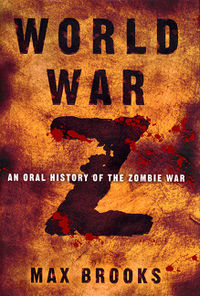

The best thing about Max Brooks’ 2006 standout novel World

War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War isn’t the

zombies. It isn’t the boogeyman horror, or the even the gut

wrenching scenes of human slaughter and loss.

No, the critical rub of WWZ — and remains so, even as a

reportedly lackluster attempt to put it to the big screen opens in

theaters this weekend — is how the United States government

completely, deliberately and categorically blew it. Let everyone

down. Lied. Obfuscated. Distracted. Placated. Fumbled in the face of

a real enemy, a true genuine, scary as all hell threat. Epic Fail.

Sound familiar?

Probably because we sense that is exactly what would happen if we were unfortunate enough to experience a nationwide catastrophic event here in the United States, or worse, on a global scale. It doesn’t have to be zombies — they are really the metaphor — it could be a pandemic, natural disaster, terrorism, affecting water, air and food supplies. Hell, a breakdown of power and the Internet would throw this country off its axis. We feel it because of the drip-drip of government lies (just think of the recent bucket load about Big Brother government surveillance), our inability to win wars, the economic collapse and its muddled recovery, the willingness to Frankenfy the food supply and ignore environmental disaster. The failure to elect politicians who don’t look like central casting for the film Idiocracy.

And then there is us. Fat, dumb and medicated aren’t exactly stellar qualifications for surviving the zombie apocalypse. America in World War Z had to learn that the hard way.

“Not Another Zombie Film?!”

A friend recently asked about the Zombie phenomenon, which has shambled on in Hollywood for a good 10 years, enjoying a tremendous tear (sorry, couldn’t help that) in recent years with AMC’s The Walking Dead series. Said friend declared zombies “silly,” and frankly, I had no good retort (though I did write about the real lure — and lore — last year, here). That said, Walking Dead is a novel take on the zombie subgenre, as it weaves horror and soap opera to great effect. Unlike the thousands of Romero knock-offs that rely solely on cheap flesh ’n gore f/x (liberal use of computer generated imagery, shaky cam and super-fast motion gives the impression of ingenuity, but it’s just a fancy cover for a weak or missing plot), The Walking Dead’s success is in traversing the human relationships born out of tragedy and fear. While the zombies continue to provide the thrills and ubiquitous tension, more recent episodes have relied less on the monsters on the road and more on the monsters in our characters’ minds. And it makes for good TV.

Max Brooks, son of the late Anne Bancroft and Mel Brooks, took that a whole lot further in World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War, and that is why, presumably, Brad Pitt paid “about $1 million” for the rights to make it into a movie (he produces, and stars in), which by all backstory accounts, deviates shamelessly from the book and as Kofi Outlaw at ScreenRant.com predicted when the word hit the streets last year, “is basically your tried-and-true (and often failed) race-against-time action/thriller.” In this case, it’s an expensive one (which means a lot of CGI) — more than $200 million dollars to make it — and if the rumors are correct it’s more Bourne Identity than Dawn of the Dead, with Pitt as the globetrotting hero who does not exist in the book and “zack” as the backdrop to his derring-do. (More on that later).

Not Really a “Zombie Book”

Where AMC’s zombie saga (based on a series of graphic novels) isn’t really interested in tackling the “big picture” — exploring the who, what, where and whatever-happened-to-the-rest-of-the-world-in-the-wake-of-the-zombie-pandemic— Brooks’ deliberative work gives us both the granular and satellite view, from the campsite to the national laboratory, from the cave to the battleship, from Tibet to the Colorado Rockies. Above all, it confirms our worst fears — that governments (the biggest, most self-interested) all over the world will keep its people in the dark until it’s too late, putting politics before humanity, petty rivalries before survival.

No surprise, the corporate media can’t be counted on for anything ahead of the zombie apocalypse, except to escalate panic and engender mass neurosis among the people. Meanwhile, all that had become critical to modern daily survival before — the impulsive consumption, fancy diets, pop-psychology, the ‘quick fixes’ and narcissistic athletic pursuits — are useless when the undead are on the doorstep and the infrastructure of reality collapses like a sandcastle. It’s like reading about the wars that preceded Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, or the nuclear holocaust that destroyed the face of the planet in H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine — complete transformation of the old world as we know it. What will rise in its place?

Brooks’s ability to weave this powerful examination benefits from its unique format. It’s really a series of interviews, with the interviewer introducing himself only at the beginning as an investigator who compiled a mountain of taped conversations all over the world for a U.N “Postwar Commission Report.” After finding that “almost half the work” was deleted in the final edition (“too many feelings, too many opinions,” he’s told), he puts the rest of the interviews in a book. This book.

As the conjured images and personal anecdotes are shocking and sad, Brooks’ decision to write it this way prevents the reader from sliding into melancholia. It’s more like a journal, or a biographical exercise, where the reader is one step removed. Strong attachments to individual characters are rendered impossible due to the briefness of each encounter. The result is “short, sharp, shock” — and awe — that a thirtysomething, first-time author could get inside the head of so many characters disparate in their ethnicity, age, religion, nationality, class. He can identify with the elderly Japanese blind man who survives the zombie war in the mountains of Kyoto, just as well the Australian commander of the International Space Station, trapped in the heavens and watching from above while the slaughter wages below (“it was like looking down on an alien planet, or on Earth during the last great mass extinction.”)

Most notable is Brooks’ obvious disdain for the Bush Administration (recall he published this at the height of the Iraq War), whom he not-so-obliquely sets up as the government in power when the pandemic breaks. China is identified as ground zero. Two separate researchers in Israel and American gather the seemingly disconnected data about reported outbreaks of reanimated dead and come to one conclusion: all hell is breaking loose.

Washington’s reaction is more horrifying than the zombies themselves, but given the enormous secrecy, the lying and perverse spin we’ve experienced recently in “real life,” this could be more prophetic than exaggerated. In short, Washington decides to stall. At first, of course, the federal bureaucracy, conditioned to its own warped survival instincts, deliberately ignores the scratching at the door. “Bob Archer,” a CIA agent who lived through the zombie war, admits to the interviewer, “I broached the subject a number of times to my coworkers … the answer was always the same, ‘it’s your funeral.’”

He continued: “I spoke to … someone in a position of authority … just a five-minute meeting, expressing some concerns (about recent outbreaks). He thanked me for coming in and told me he’d look into it right away. The next day I received transfer orders: Buenos Aires, effective immediately.” The interviewer then asked the CIA agent if the agency had seen the researchers’ report about the global Pandemic, which had later become a textbook for the anticipated crisis. He responded: “It was found at the bottom of the desk of a clerk in the San Antonio field office of the FBI, three years after the Great Panic.”

Brooks’ Karl Rovian character in World War Z, reduced to a postwar fuel technician (dung digger) in Amarillo, Texas, tried to explain why, even after Washington was fully briefed about the coming plague and the surge of undead, it did everything it could to avoid full disclosure:

What, you would have rather we told people the truth? That is wasn’t a new strain of rabies but a mysterious uber-plague that reanimated the dead? Can you imagine the panic that that would have happened: the protest, the riots. The billions in damage to private property? Can you imagine all those wet-pants senators who would have brought the government to a standstill so they could railroad some high-profile and ultimately useless “Zombie Protection Act” through Congress? Can you imagine the damage it would have done to that administration’s political capital? We’re talking an election year, and a damn hard, uphill fight …

[The American people] thought they’d been through some tough times already, and it would have been political suicide to tell them that the toughest ones were actually up ahead.

How many perished because they were kept in the dark is untold. Eleven million, for example, died in the winter after the situation could no longer be explained away by health officials and politicians and assuaged by the placebo vaccines bankrolled by the government (“it calmed people down and allowed us to do our job,” the Rovian “Grover Carlson” said of the Phalanx “vaccine”).

Brooks’ wants us to know that the country finally finds its way. The turning point is a spirit-crushing defeat in the Battle of Yonkers, a marker in the war in which America lost whatever was left of its “exceptionalism,” its identity vanquished because the military’s pre-zombie superiority turned out to be, well, useless (“Yonkers was supposed to be the day we restored confidence to the American people,” said “Todd Wainio,” a grizzled U.S. Army veteran, “instead we practically told them to kiss their ass goodbye”). But restoration only occurs after the country is forced to make a series of morally wrenching decisions, engage in pure societal selflessness and austerity beyond our modern imagining — all things Brooks implies the America of today is truly unprepared to do.

How different are the conditions here in “the real world”? Recent events indicate not much. For one, we know whistleblowers definitely engineer their “own funerals” when they question the government’s policy and practices. Often, like in the cases of Thomas Drake and Walter Binney and Diane Roark — even Bradley Manning — whistleblowers first exhaust conventional channels for their complaints but are typically ignored or rebuked by The Body anyway. Brooks captures this poisonous Washington mindset, mired in political pusillanimity, which we see everywhere in the national security state right now.

Case in point: Edward Snowden reveals a massive deviation from the electronic surveillance we believe is being conducted under the auspices of the FISA court. In the interest of CYOA, politicians from Diane Feinstein all the way up to the President himself, claim they knew this was going on the whole time, and that it was “nothing new.” Sen. Bob Corker told an audience in Washington Wednesday that he had been briefed on the NSA program but was “not aware of” its broader applications. However, after more recent “discussions” following the Snowden fallout, Corker feels better about their legality. Classic.

Meanwhile, Rep. Peter King, head of the House Homeland Security Committee, wants to put journalist Glenn Greenwald in jail.

Do you really want these guys anywhere near our nuclear stockpile or even on first watch during the zombie apocalypse? And what about your neighbors, the ones who think our constitutional rights should be tossed out the window because these stumblebums in congress say so. Sheeple are usually the first ones to get it, at least they do in the movies.

Back to the film. Unfortunately, when handed a narrative with such delicious possibilities, Hollywood again grinds out a sausage, assembled by committee, that’ll likely leave the viewer with an empty pit (no pun intended) in the stomach rather than food for thought.

Sure folks may like the colorful eye candy treat of watching Brad race against time in a “punchy, if conventional action thriller” in theaters this Friday, but if you want to experience where we are headed, read the book or listen to the audio version. It’ll give you more than just zombies to fear, because let’s face it — the boogeyman, really, is ourselves.

Follow Vlahos on Twitter @KelleyBVlahos