There is a scene in the 1946 classic The Best Years of Our Lives when Homer Parrish, played by real World War II veteran Harold Russell, shows his girl what it is like to dress himself for bed with the rudimentary metal hooks that have replaced his left and right hands in the war.

“I want you to come upstairs and see what happens,” he says, daring Wilma to bear witness to his shame, and what could be her own tragic burden if she chooses to stay with him. The girl next door comes through this test with such grace and understanding that the audience breathes a collective sigh of relief – Homer, the former All-American high school athlete, now with two hooks for hands and meager prospects, will have this angel for a wife. All is good in the world.

I have always had mixed feelings about this film, which was directed lovingly by William Wyler, a director of renown who also survived World War II as a major in the U.S. Army Air Forces. There is a maturity and realism, albeit soft and sometimes fleeting, about this character study, which explores the repercussions of quickie pre-deployment marriages, divorce, depression, alcoholism, unemployment, disability, and ordinary civilian readjustment. Fred Derry, played by a straight-on Dana Andrews as the former Air Force “glamour boy,” finds himself at one point in the aircraft graveyard with a flashback coming on. He is headed for those graves, a dusty, banged-up hull of a man – until someone, another vet, gives him a job, and he gets a second chance at living the American dream circa 1946.

But the movie is propaganda, and we know it. For every glimpse of dissent within the film – and there are very few – there is a war hammer slamming down, reminding the audience that the conflict was right, the war was necessary, and these men sacrificed their bodies and their souls for a noble cause. Like every other Hollywood post-war movie of its time, it never crosses a line. Sure, we are compelled to reflect on how “war is hell” and on the quiet suffering of the veterans and loved ones in the story, but we must never think too hard about what got them there in the first place.

Sadly, after 65 years of war and movies and war in the movies, Hollywood still lacks the guts to do it right. It is no better now at conveying the brutality of the meat grinder, the arrested development of a fellow human being, or the government’s systematic betrayal of its people than it was in the era of prefab suburban tract homes and Artie Shaw. In fact, it may be worse. While The Best Years compelled the mainstream audience to rally the national identity around the veteran – however manipulatively – today’s movies promote perpetual adolescence, with very little interest at all in what could be the warping of a generation. Instead, today’s veterans are invisible (and the new A-Team remake doesn’t quite count as evidence to the contrary).

Surely, there are those of us who don’t care, who see veterans as not only voluntary agents of an abominable war policy, but also as only a small percentage of the American population.

But consider this: however lamentable it may be, Americans continue to look to popular culture for a shared identity and consciousness, and in that spirit, Hollywood has been effective in propagandizing war – most often against our best interests – whether in the form of the unreflective boosterism of World War II or the apologetic melodrama of post-Vietnam, which eventually led to the steroidal backlash movies of the Reagan era.

By ignoring our current nine-year war’s effect on our hearth and home completely, Hollywood is engaging in its most effective propaganda ever, because as a result there is no collective, national resistance, at least not enough to prevent Americans from moving sheep-like through two war presidencies, tacitly approving routine troop increases, huge defense budgets, and an evolving foreign policy that brings us closer to additional conflicts in places like Yemen and Iran.

In effect, Hollywood is keeping the war machine in business.

Sure, there have been attempts to keep veterans in the spotlight, but those have either fallen flat or baldly advanced pro-war propaganda. For instance, Stop Loss was a 2008 film about soldiers subject to the real-life Pentagon policy that forces some to remain in the Army beyond their terms of duty, a barely remembered movie that reviewer Stephanie Zacharek called “so dramatically tedious that it feels remote instead of resonant … so aggressively mediocre that you’re forced to guilt yourself into caring about the characters in front of you.”

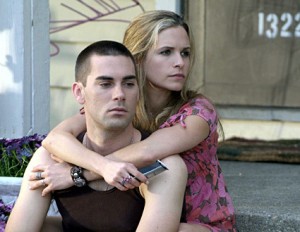

Last year gave us Brothers, a remake of a critically acclaimed Danish film, which not surprisingly, Hollywood managed to turn into something few wanted to see. It’s the story of an upstanding Marine who is brutally traumatized as a prisoner in Afghanistan, only to return home to find his wife and ne’er-do-well brother bonding over what they had presumed was the Marine’s death. Violence and drama ensue. Reviews were mixed, with the worst calling it a “corny tale, told with both generous helpings of deli-sliced cheese” and “more clichés than one movie can survive.”

(Note: While audiences may also find the aforementioned Best Years cliché-ridden, the characters and performances ultimately drive the story. We cannot say the same for today’s Hollywood confections, most of which depend solely on stitching one tired trope to another for effect.)

Then there is the rare “indie” film that strives to redeem American movie-making. Done right, it’s feted by all scrupulous reviewers and generously bestowed with statuettes by the industry during Oscar season, but nonetheless saddled with a range of zero in audience saturation and thus largely ineffective in its mainstream impact.

The Messenger fit that bill in 2009. A grim character study, it tells the tale of an Army lifer and a painfully injured Iraq vet who serve to inform NOKs (next of kin) of their loved ones’ deaths. With restraint, and “without sensationalism and political posturing,” The Messenger is a respite from the preachy treacle Hollywood typically dishes for our ultimate viewing displeasure. In fact, there is as much positive consensus about The Messenger as there was for Avatar. But while Avatar reached a planet-wide audience and drew $747 million at the box office, The Messenger was shown in a limited number of movie houses and earned $1 million.

On the other hand, though more an examination of active soldiers than a film about veterans, The Hurt Locker won accolades and Academy Awards – including best picture – for its brutal, realistic depiction of an ordnance disposal team in Iraq. But like most of these kinds of movies, any antiwar impression on the national psyche appears negligible. While it was deft at delivering the “war is hell” message, giving Hollywood its first chance in nine years to deliver a counterpoint to war that it could be proud of, not all were convinced that The Hurt Locker wasn’t more pro-war Hollywood propaganda, just better disguised and therefore more effective.

As Tara McKelvey wrote in July 2009:

“The Hurt Locker sets itself up as an anti-war film.… Yet for more than two hours, the film imbues Baghdad’s combat zone with excitement and drama. In one scene, a bomb-defuser, Staff Sgt. William James (Jeremy Renner), searches for a detonator in a car loaded with explosives, and later he tries to save an unfortunate Iraqi man who has been forcibly strapped with homemade bombs.… It is easy to understand why the soldier, William James, would take so much pleasure in his work as a daredevil bomb-defuser in Iraq, and find so little to be happy about in the difficult, messy world of America when he comes home.

“Back in the United States, James finds himself in a supermarket aisle, trying to decide between Lucky Charms and Cheerios. He stares at those brands and then at dozens of others on the shelves, feeling overwhelmed by the dizzying array of breakfast cereals, in a scene of American consumerism gone amuck. He then spends part of the day cleaning soggy leaves out of the gutter of his house. It is a dull, dreary world. A moment later, however, a soldier is shown striding down a wide, dusty Iraqi road in a NASA-like bomb suit, filled with a sense of purpose, courage, and even nobility that does not exist in suburban America.

“The film draws a sharp contrast between the tedium of American life, with its grocery-shopping, home repairs, and vapid consumerism, and the heart-pounding drama of the combat zone in Iraq. The fact that the war itself seems to have little point fades into the background. For all the graphic violence, bloody explosions and, literally, human butchery that is shown in the film, The Hurt Locker is one of the most effective recruiting vehicles for the U.S. Army that I have seen.”

Unfortunately, for the same reasons, even the best and most devastating of the modern battlefield movies – think Apocalypse Now, Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, and We Were Soldiers – all depict the futility and waste of war, yet never provoked widespread reactions beyond pity, horror, and regret. War movies concentrate on men doing heroic things in chaotic and extraordinary circumstances. But they typically end before the GI goes home – if he goes home. Without exploring the unglamorous, often banal, lifetime sentences of injured veterans, the messy divorces, the screwed-up kids, the booze and pill-popping and routine visits to depressing VA hospitals, we will never move beyond despising war in its symbolism to protesting the current war for what it has done – and is still doing – to us as a country.

Many will note that Hollywood attempted to make up for its negligence by producing movies like The Deer Hunter and the Jane Fonda redemption movie Coming Home during the 1970s – and in some ways, these attempts were welcome. As ham-handed as The Deer Hunter might have been, for example, it was the kind of movie that at the time brought attention to the broken lives of veterans of all wars. Remember, it wasn’t until 1980, two years after The Deer Hunter was released, that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was even recognized as an official diagnosis.

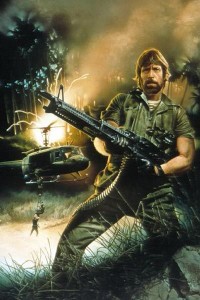

Unfortunately, by 1982 the political winds and the popular culture had decided so-called self-pity and reflection was un-American, and macho Vietnam franchises like Chuck Norris’ Missing in Action and Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo: First Blood led the way back to heroic war propagandizing that muddled whatever lessons we might have taken away from Vietnam. We are programmed now to “support our troops,” but somehow over the last 20 years that’s become synonymous with supporting Uncle Sam’s war policies, too. Quite convenient.

So Hollywood expends all of its talent

and resources now to make epic movies about the “Good War” fought

by “The Greatest Generation,” ranging from pure pandering schlock (Pearl

Harbor) and earnest

alternative tributes (Flags of

Our Fathers, Letters

from Iwo Jima) to Spielberg

box-office bonanzas (Saving

Private Ryan) and HBO series (Band

of Brothers, The Pacific). These were all propaganda to varying degrees, designed to

keep the country in step and reluctant to protest a war ever again.

Meanwhile, the only network television programming that acknowledges there is even a war going on today is the Lifetime Channel’s Army Wives, which doesn’t hide the fact that it partners with and gets technical advice from a number of pro-military organizations, if not from the U.S. Army itself. It even incorporates recruiting into its scripts. The soldiers and husbands are hunks, while the wives are babes who are more heroic for every sacrifice they make (which are as hackneyed as it gets). Ugliness and complication are sanitized for the target female audience and, more often than not, resolved by the end of an hour. This is one show where you won’t see a primary character injured on the battlefield and transformed into a bloated and drooling shell of himself, entirely dependent on his wife for care. It’s about the soap, after all, not the grit.

One look at the Army Wives Web site says it all. Contemporary American culture, so much more vain and uniform than that of the Best Years era, has not only stunted our capacity to think for ourselves, but has made war and its aftermath another narcissistic melodrama. It makes someone like me sentimental for movies like The Best Years, a film that – however flawed – endeavored to bring viewers to some sort of human recognition. But even more sadly, it explains in part why, at nine years and counting, we still don’t have the will or authority to put an end to what we all know is wrong.