With the Cold War ending in the early 1990s, some Western scholars predicted a more peaceful world with liberal democracy the only game in town. The findings of the Global Peace Index suggest otherwise.

The twelfth edition of the Global Peace Index (GPI) reports that the global level of peace deteriorated by 0.27 per cent last year. Europe and United States, the world’s most peaceful regions, recorded a decline in peacefulness for the third straight year. This is not merely a one-year decline. Rather, it’s part of a decade-long trend: global peacefulness has deteriorated by 2.38 per cent since 2008.

The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), a non-partisan think tank headquartered in Sydney, has been publishing yearly editions of GPI for the last 13 years. Covering 99.7 per cent of the world population, the index ranks 163 independent states and territories in three domains – safety and security in the society, involvement in ongoing conflicts, and militarization – according to 23 qualitative and quantitative indicators.

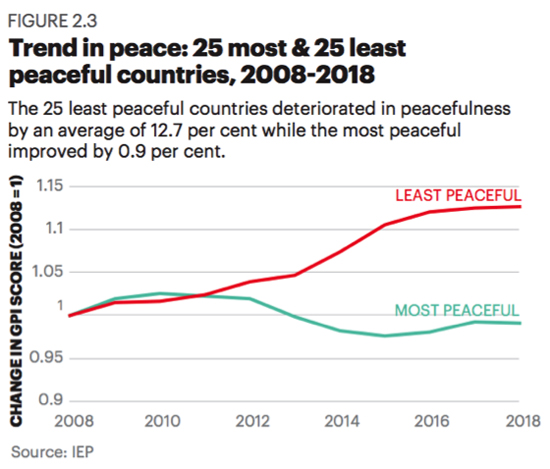

In addition to presenting the findings for the last year, this year’s edition also includes analyses of trends in positive peace: the attitudes, institutions, and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies. It turns out that much like the trend of the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, the most peaceful countries are getting more peaceful whereas the least peaceful are further declining on the scale.

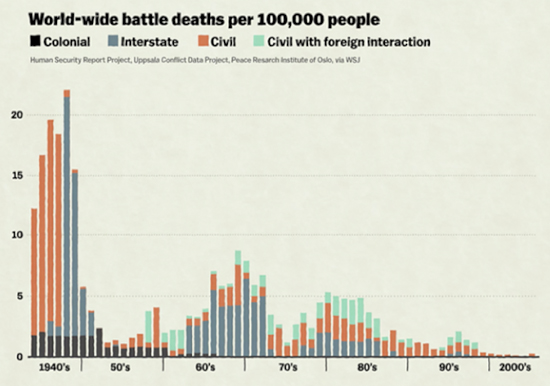

The major reasons for the deterioration in global peace are ongoing violent conflicts. A century after World War I, the theater of war has shifted from interstate conflicts in Europe to internationalized civil wars and terrorist violence in the Middle East, North Africa, and Latin America. International powers are involved in one-third of all armed conflicts, making them intractable. At the same time, a dramatic increase in deaths, the majority of which are civilian, has taken place only in a handful of countries. That should explain why ill-fated Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq persist among the bottom five countries.

Sustaining these high levels of violence comes with an economic cost, which the GPI estimates at around $14.76 trillion for 2017: roughly $2,000 per person on the planet. Consider, for example, the costs of violence at the Siachin Glacier, a 50-mile stretch of Himalayan glacier, a source of pointless contention between two nuclear-armed nations, Pakistan and India. Researcher Sajjad Padder estimates that a Pakistani soldier dies every fourth day and an Indian soldier every other day – solely because of weather conditions on the glacier and without a single shot fired. India and Pakistan together spend an estimated $350 million every year to maintain soldiers in unlivable conditions of 70 degrees below zero. Associate Professor Happymon Jacob at Jawahir Lal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, argues that this military standoff is “mostly symbolic and political, not strategic or military.”

Intractable conflicts in the Middle East have affected Syria and Iraq the worst but the spillover effect from these conflicts has also contributed to deterioration in the ranks of more peaceful and richer countries. Commenting on this interconnectivity in a more globalized world, Middle East expert Phyllis Bennis explains, “Europe and Middle East are not separable anymore. The Syrian conflict is more than a civil war. It is also regional, sectarian, and global where Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, United States, Russia, United Arab Emirates, Jordan are all involved.”

Other than the countries directly involved, the Syrian conflict also continues to affect other countries indirectly by producing more than six million refugees worldwide. “Violent conflicts in the Middle East have affected governance and societies everywhere, most notably the United States which has enacted controversial laws such as the Muslim travel ban,” adds Bennis. “Clearly, human rights has given up its standing on the priority list to nationalism.”

The United States, meanwhile, has a very poor showing in the GPI. Its ranking is 121, just above Myanmar and well below Honduras, El Salvador, Rwanda, and Burkina Faso. Although the United States has done poorly in terms of safety and security as well as ongoing conflict, its rank in the militarization domain is particularly dire: fourth from the bottom, below Syria and above only North Korea, Russia, and Israel. The report notes that the US score has deteriorated across all three domains since last year. “For a number of years, the United States has scored the worst possible scores on such variables as incarceration, involvement in external conflicts, weapons exports, and nuclear weapons” says the report.

“The United States spends more on its military than any country in the world – all while its politicians claim not to be able to afford measures like universal health care and free or low-cost higher education that are commonplace in other wealthy nations,” notes Lindsay Koshgarian, program director for the National Priorities Project. “At the same time, the U.S. military polls as citizens’ most trusted institution, above organized religion, the media, public schools, the courts, and far above Congress. A good deal of American exceptionalism – the belief that America is and always will be ‘number one’ – seems based on wartime victories going as far back as World War II.”

Some regions and countries have improved their measures of peace. The election of new president Adama Barrow in Gambia has improved relationships between Gambia and its neighbors, particularly Senegal. Gambia, thus, improved from number 111 last year to 76 in this year’s report. Countries in Eastern Europe also improved their scores whereas Asia Pacific retained its position as the third most peaceful region in the world.

Chic Dambach, Woodrow Wilson visiting fellow at Johns Hopkins University, is positive about overall improvement in human conditions. “Hunger, poverty, infant mortality have declined dramatically, and democracies have emerged in much of the world,” he points out. “All of that is to the good and worthy of celebration.” However, despite the sharp decline in interstate conflicts and deaths of military personnel, the significant number of deaths of civilians in the civil wars continues to pose threat.

Dambach is also concerned about the renewed arms race between China, Russia, and the United States. “The newly launched G. R. Ford aircraft carrier cost $13 billion with two more on the way, and the acquisition cost of the F-35 is $406 billion,” he notes. “The actual combat utility of these and other new weapons systems in a climate of asymmetrical warfare is questionable, but the benefit to the arms industry is clear. Sadly, as these tools of destruction are produced, some may feel compelled to use them. Therein lies great risk and a call for a new movement for peace.”

Sajjad Hussain is a Rotary Peace Fellow at the University of North Carolina (UNC) and a Next Leader at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS). He tweets at @Changovski. Reprinted with permission from Foreign Policy In Focus.