The Japanese government denies some fears that its forces will be subordinate to U.S. forces. However, the U.S. and Japanese forces are being integrated, and there is a secret agreement that a single commander is indispensable in an emergency and that the U.S. should appoint the person.

Japan will create the Joint Operations Command (JJOC) of Self-Defense Forces by the end of March 2025. Currently, the Joint Staff Office is responsible for military advising and assisting the Prime Minister and Defense Minister and for commanding the military operations of the Ground, Maritime, and Air Self-Defense Forces. However, the new joint headquarters will accept commanding the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, and this change will relieve the Joint Staff Office’s burden and enable it to concentrate on advising.

In April 2024, the U.S. and Japan issued a Joint Leaders’ Statement: Global Partners for the Future. In the statement, the U.S. welcomed “plans to stand up the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) Joint Operations Command to enhance command and control of the JSDF.” They announced their intention to bilaterally upgrade their respective command and control frameworks to enable seamless integration of operations and capabilities and allow for greater interoperability and planning between U.S. and Japanese forces in peacetime and during contingencies.”

In June 2024, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said appointing a four-star general to head of U.S. Forces Japan was still considered. Currently, the U.S. Forces Japan’s head is a three-star general, and the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, based in Hawaii, has command authority over U.S. Forces in Japan, which head is a four-star general. However, there is a distance and a time difference between Hawaii and Japan. In order to cooperate smoothly with Japan in operational planning and training to respond to contingencies, the authority of the U.S. Forces Japan headquarters should be strengthened.

On July 28, 2024, the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee (U.S.-Japan “2+2”), which both countries’ Foreign Affairs Ministers and Defense Ministers attended, released a joint statement. In the statement, the U.S. announces that it “intends to reconstitute U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ) as a joint force headquarters (JFHQ) reporting to the Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM). This reconstituted USFJ is intended to serve as an important JJOC counterpart” to facilitate deeper interoperability and cooperation on joint bilateral operations in peacetime and during contingencies.

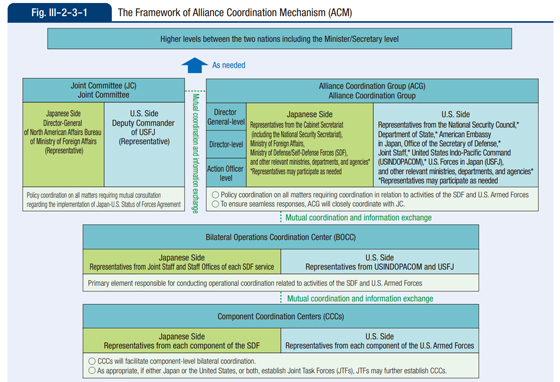

The Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) Joint Operations Command will be included in the Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM).

The Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM) was established in November 2015 by the U.S. and Japanese governments for bilateral Defense Cooperation. The ACM coordinates policy and operational aspects of activities conducted by the U.S. Forces and JSDF in all phases, from peacetime to contingencies. This Mechanism also contributes to timely information sharing and the development and maintenance of common situational awareness.

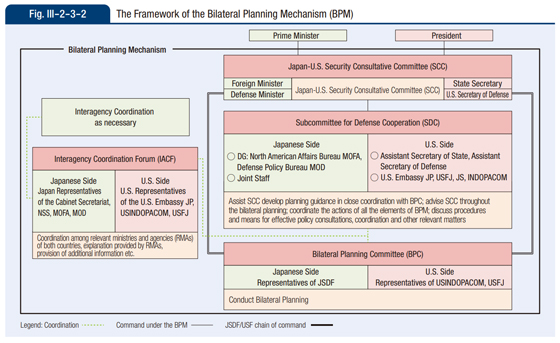

On the same day, Washington and Tokyo also established the Bilateral Planning Mechanism (BPM), which ensures Ministerial-level directions and supervision and the involvement of relevant government ministries and agencies. It also coordinates various forms of U.S.-Japan cooperation conducive to the development of bilateral plans. The two governments conduct bilateral planning through the BPM.

Both Mechanisms are based on the Guidelines for U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation, published in 1978 and revised twice in 1997 and 2015. The Guidelines are documents agreed upon on what defense cooperation should be concretely based on the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, and the alliance was advanced beyond offering bases. Though the guidelines read that it does not obligate either government to take legislative, budgetary, or administrative measures, Tokyo has enacted laws and spent money to fulfill them.

The 1978 Guidelines were laid down on the assumption that the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hokkaido, Japan. They stated that the U.S. and Japanese forces endeavor to achieve a posture for cooperation, conduct studies on joint defense planning, and undertake necessary joint exercises and training in order to perform coordinated operations jointly.

The 1997 Guidelines aimed at creating “a solid basis for more effective and credible U.S.-Japan cooperation under normal circumstances, in case of an armed attack against Japan, and in situations in areas surrounding Japan.” The Guidelines declared to establish the bilateral coordination mechanism, which was operated only during contingencies, and both countries should cooperate in situations surrounding Japan that would have an essential influence on Japan’s peace and security. “Areas surrounding Japan” was not geographic but situational. This change enabled Japan to conduct logistics support activities for U.S. Forces that are conducting operations to achieve the objectives of the Security Treaty even if there is no attack on Japan.

The U.S. and Japan revised the Guidelines in 2015, which are still effective. The 2015 Guidelines extended both countries’ cooperation sphere to the Asia-Pacific region and beyond.

The Guidelines state the establishment of the abovementioned Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM) and reflect the 2014 Japanese Cabinet approval for exercising the right of collective defense. Japanese “Self-Defense Forces will conduct appropriate operations involving the use of force to respond to situations where an armed attack against a foreign country that is in a close relationship with Japan occurs and as a result, threatens Japan’s survival and poses a clear danger to overturn fundamentally its people’s right to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness, to ensure Japan’s survival, and to protect its people.” The Guidelines also declare that “Japan and the United States will cooperate as appropriate with other countries taking action in response to the armed attack.”

Article 9 of the Japanese constitution prohibits maintaining military force and states renunciation of war. So, the use of force even for self-defense and the existence of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces and the U.S. Forces in Japan are unconstitutional. However, the Japanese government has interpreted the text broadly and admitted the minimum use of force for self-defense. Now, Tokyo includes exercising the right of collective defense in the minimum use of force for self-defense and makes noncommittal explanations to leave room for further broad interpretation.

On July 29, 2024, Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Toshimasa Hayashi denied fear that Japanese forces would be subordinate to the U.S. forces. He stated, “All Japanese Self-Defense Forces operations are conducted based on this country’s judgment. There is no change in policy that each force operates in accordance with its own chain of command.”

However, there was a secret agreement. On July 23, 1952, U.S. Ambassador to Japan Robert Murphy, U.S. Far East Commander in Chief Mark Clark, and Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida agreed that a single commander was indispensable in an emergency and that the U.S. should appoint the person. Yoshida asked that this agreement be kept secret because it would significantly impact the Japanese public.

Japan intends to play a significant role in a war as the world’s biggest host nation of the U.S. military. The U.S. has been completing its long ambition to fully use Japan in order to wage war and dominate the world.

Reiho Takeuchi is a Japanese journalist whose work focuses on the geopolitical issues in the Asia-Pacific. He writes at https://reihotakeuchi.substack.com/. E-mail: reihotakeuchi@gmail.com.