It was neoconservative pundit Charles Krauthammer who, in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, inaugurated Washington’s unipolar moment.

"America is no mere international citizen. It is the dominant power in the world, more dominant than any since Rome," he wrote then, before the Afghan and Iraq wars, before Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay, before the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

But the United States’ "moment" as an unchallenged superpower was just that – a moment, a finite period of time, 30 or 40 years to "reshape norms" and "alter expectations." In this new age of empire, Washington would "create reality."

How? "By unapologetic demonstrations of will," wrote Krauthammer.

Five years after President George W. Bush declared "mission accomplished" aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln – and no apologies later – Washington’s hegemony in the Middle East has deteriorated, and along with it, the president’s popularity.

The neoconservatives’ utopian fantasies of a democratic Iraq have evaporated, as have notions of U.S. military invincibility. And as the U.S. policy crumbles, allies and "enemies" gather to pick up the pieces.

Brent Scowcroft, national security adviser to two U.S. presidents, conceded about Iraq in 2007, "We are being wrested to a draw by opponents who are not even an organized state adversary."

To understand how the U.S. arrived at its present condition, how things related and not became part of the same "axis of evil," and how neoconservatives’ "unapologetic will" morphed into Bush’s hubris and subsequent political failures, it behooves us to "keep the past in mind."

Especially as we look toward an uncertain future.

And that is exactly what Tom Engelhardt – of the popular blog TomDispatch – does. When it comes to the recent past, Engelhardt tries "not to forget the remarkable record of the Bush administration in its various wars."

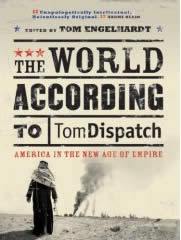

His most recent offering, titled The World According to TomDispatch: America in the New Age of Empire, is a collection of essays culled from the site over several years, and offers a striking portrait of the limitations of U.S. power in the post 9/11 world.

His most recent offering, titled The World According to TomDispatch: America in the New Age of Empire, is a collection of essays culled from the site over several years, and offers a striking portrait of the limitations of U.S. power in the post 9/11 world.

This collection is a factual rebuttal of the neoconservative argument for unilateral action and interventionism, and it will certainly ruffle the feathers of an administration and its supporters with an historical sense of the world, or one that extends – selectively – only to Pearl Harbor.

In this new age of empire, it is essential to read between the lines of political rhetoric. As Engelhardt writes in the introduction, "Despite much talk of ‘democracy’ and ‘liberty,’ a Hellfire-missile-armed Predator drone would perhaps be the truest hallmark of the early-21st-century American civilization they presided over."

As author and editor, Engelhardt has provided the reader with sophisticated political analysis that includes essays, letters, correspondence, and dispatches by celebrated authors and intellectuals. It is accessible and poetic, unshackled by the turgid writing that keeps most academics on the fringe of mainstream discourse.

Whether he is scouring the Internet for statistics and buried news reports of U.S. air strikes, or hidden in the recesses of the New York Public Library, searching for historical accounts on microfiche, Engelhardt digs deep. And in doing so, he sheds light on the sobering reality of the new age of empire and its painful contradictions.

In a May 2006 essay, titled "The Billion Dollar Gravestone," he considers the Ground Zero memorial, the Freedom Tower to be built in the footprint of the original World Trade Center towers, which is expected to reach exactly 1,776 feet into the sky.

The project, meant as a memorial to those who died on that fateful day, will cost anywhere between $500 million and $1 billion, a sum exponentially greater than any other U.S. war memorial built before it.

In May 2006, when the number of U.S. soldiers killed in Afghanistan and Iraq exceeded 2,700, he asked, "Who thinks that the United States will ever spend $500 million, much less $1 billion, on a memorial to the ever-growing numbers of war dead from those two wars?"

Who thinks the U.S. will spend that much now that more than 4,600 have died?

As the author writes, "What was built on Ground Zero will mainly memorialize a specific America that emerged from the rubble of 9/11."

Engelhardt’s work – and those he selects from the blog – read like poetry. In the rapid-fire blogger world, he breaks the mold by sticking to the old ways: he writes essays. And his work has only been strengthened by the addition of other fine contributions.

In one, celebrated intellectual and war critic Noam Chomsky asks, "What if Iran had invaded Mexico?" As he writes, a new study using "government and Rand Corporation data" reveals that, as of March 2007, the Iraq war has already led to a "sevenfold increase in terror," a statistic that invalidates the Bush administration’s claims to the contrary.

But most crucially, Chomsky turns mainstream discourse on its head, critiquing notions of objective truth and underscoring the limits of acceptable U.S. public debate. "The cruder of two systems leads, naturally enough to disbelief," he writes. "The sophisticated variant gives the impression of openness and freedom, and so far more effectively serves to instill the party line. It becomes beyond question, beyond thought itself, like the air we breathe."

Another essay, written by Chalmers Johnson and titled "Smash of Civilizations," details the looting of antiquities in Baghdad, and the U.S. failure to stop it. "Our occupation forces were letting perhaps the greatest of all human patrimonies be looted and smashed," writes Johnson. (Note: the editors and authors have dedicated a portion of the royalties from this book to the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage.)

And the discussion extends beyond the Middle East. Other essays deal with U.S. plans in the Far East; the rearmament of "pacifist" Japan to offset Chinese interests; pseudo-states; the "tri-border" area in Latin America, where al-Qaeda is rumored to be, but where the lack of evidence suggests it is not; gunboat diplomacy; personal accounts from Hamra Street in Beirut, during the Israeli siege of Lebanon in the summer of 2006; comparisons between the U.S. discourse used to prosecute the "Global War on Terror" and, more than a century earlier, the American Indian wars.

Engelhardt and contributors to this book detail the Bush administration’s super-sized response to the 9/11 attacks, reminding us of the past, providing a fuller picture to analyze America’s "moment."

On the night of the terrorist attacks, the president warned the citizenry of the U.S. that the "our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there."

With the U.S. footprint looming large over the world, does it make us any safer?

"Don’t be ridiculous," writes Engelhardt.