The burst of good old-fashioned "isolationism" on the Right that followed the implosion of Communism and the end of the Cold War is in danger of sputtering to an abrupt halt. From Pat Buchanan to Gary Bauer to the congressional Republican leadership, just about every political leader and ideologue of a conservative hue has been snookered by a concerted campaign to demonize China as the new Evil Empire. A grand coalition that spans the spectrum, from the AFL-CIO to the American Conservative Union, is beating the drums for war with China.

The labor unions want a trade war, as does Buchanan; the neoconservatives are naturally in favor of any war, so long as it serves their vision of a foreign policy that frankly aims at "world hegemony," as Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol likes to put it. Some Religious Right leaders, notably Bauer, having despaired of ever abolishing the National Endowment for the Arts, and, otherwise largely ignored by the Republican congressional leadership, have signed on to the holy war against "Red" China, alleging anti-Christian persecution. The Hollywood crowd, steeped in New Age mysticism and enamored of Tibetan Buddhism, is waging a war of images, with Sinophobic movies such as Kundun. Bootlegged videos have flooded the Chinese market, and the movie moguls are miffed; this, combined with Tinselstown’s penchant for stagy self-righteousness, has propelled the glitzy and the glamorous into the front ranks of the China-haters.

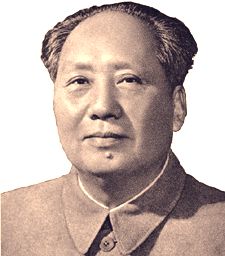

The Sinophobes almost never refer to China as simply ‘China," but instead raise the specter of "Red" China, or "Communist China." Of course, it was never called this during the halcyon days of the Cold War, during the era of Mao Zedong, when China was in the throes of the "Cultural Revolution" – a mass ideological exorcism in which "bourgeois capitalist-roaders" within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were sent to reeducation camps, and peasants were forced to live in agricultural "communes," in which they worked, ate, and slept together like a vast hive of worker bees. For Mao had not only broken with the Kremlin, but deemed the Soviet "social imperialists" far more dangerous than the United States. Nixon’s trip to China signaled the beginning of a wide-ranging strategic and military alliance between the two nations. While a very few conservatives rallied around their old ally, Taiwan, most proclaimed Nixonian diplomacy a stroke of genius and from that moment on no more was heard about human rights violations in China until well after the end of the Cold War.

How Red Is China?

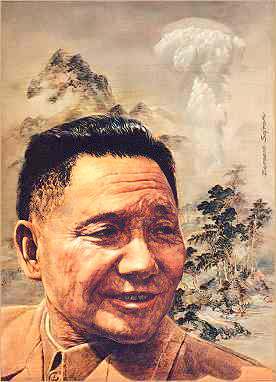

After Richard Nixon raised his glass in salute to the People’s Republic, "Red" China dropped entirely out of the conservative lexicon. The great problem in reviving it is that a wave of reform has washed the redness out of China so thoroughly that it is, today, not even a barely discernible pink. Since the death of Mao, in 1979, and the ascension of Deng Xiaoping as China’s new "great helmsman," China has shed Marxist orthodoxy in all but the formal sense. Far from promoting Marxist ideology, or serving as the center of a revived worldwide Commie Conspiracy, the Chinese Communist Party is presiding over the largest-scale destatization process ever attempted: in "constructing socialism with Chinese characteristics," as they put it, the heirs of Mao and the Long March are systematically dismantling the economic foundations of socialism. Selling off state industries, not only allowing but actively soliciting foreign investment, privatizing land, cutting back on the military, setting up Special Economic Zones in which the deadening hand of the Party and the bureaucracy is stayed and the market allowed to flourish virtually unhampered – these and a host of other radical measures have effectively abolished the economic dictatorship of the Party and the State. The dour spirit of Maoist egalitarianism, which exhorted China to "put politics in command," has given way to a new form of "socialism" summed up by Deng in a famous maxim: "To get rich is glorious!"

While Chinese Marxist theoreticians insist on referring to their system as "market socialism," it is no more socialist than the economies of Europe and the United States – and no less. In many respects, the burgeoning Chinese private sector is far less regulated than in the West. China has no "civil rights" laws, no Chinese With Disabilities Act, no affirmative action. Western commentators of the liberal persuasion bemoan the lack of "social welfare’ measures, such as workman’s compensation, and demand that Chinese be given the alleged "right" to organize unions.

China: The Invisible Empire

At the end of Deng Xiaoping’s life, in the final throes of his struggle against the remaining orthodox Maoists in the CCP leadership, the aging leader took to the stump and made his case to the Chinese people. Traveling throughout South China, and touring the special economic zones, he argued forcefully for more rapid privatization and the unleashing of market forces. As Orville Schell puts it in his book, The Mandate of Heaven, "Deng’s nanxun [Southern tour] had rammed Chinese society into reverse gear, stampeding the country into a form of unregulated capitalism that made the U.S. and Europe seem almost socialist by comparison."

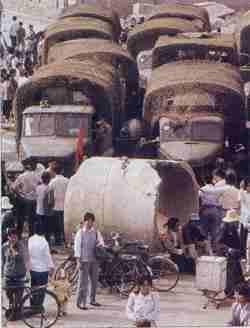

With the standard of living and growth rates rapidly rising, ordinary Chinese have never been better off. But that does not satisfy the ‘human rights" crowd: far from it. China may be taking the capitalist road, they carp, but it is still a long way from achieving "democracy." This obsession with capital-d Democracy overshadowed Clinton’s trip to China, and so skewed the focus of the American media, and, ultimately, the President himself, that the main subject of public discussion was not the dramatic achievements of the post-Mao destatization, in which a billion people lifted themselves up out of serfdom. Instead, the President engaged in an hour-long colloquy with Chinese premier Jiang Zemin on the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, in which a few hundred rioters bent on self-immolation achieved their stated ends.

The Myth of Tiananmen

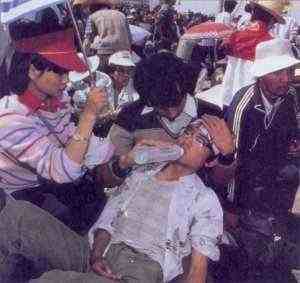

The Tiananmen Square "massacre" is an incident so wrapped up in mythology, most of it generated by Western journalists and their professional dissident friends, that it is nearly impossible for any "revisionist" analysis to be given a hearing. The world saw the Goddess of Democracy, the bright banners and youthful idealism of the protesters, a giant rock-concert held under the gaze of the seemingly incongruous Chairman Mao, whose gargantuan portrait dominates the Square.

Indelibly etched on the popular mind is the image of a lone man standing in the path of an oncoming tank. The tank moves to the left, and then to the right, in a fruitless effort to avoid flattening him. This sequence of events could serve as a kind of shorthand for the events leading up to the infamous incident.

Ensconced in the Square for weeks on end, the students were at first hailed by the radical reform wing of the CCP, and even some of the more orthodox, as the harbingers of a new spirit of "socialist democracy." Hu Qili, the party chieftain in charge of press and propaganda at the time, was in sympathy with the students’ democratic demands, and gave the go-ahead to the media to open up and begin to report what was happening in the Square. The students were duly rewarded with a front-page photo and adulatory news story in the May 5 issue of the official Peoples Daily.

That is why those discount the recent student-led protests against the bombing of China’s Belgrade embassy as government-staged and therefore of limited significance miss the point completely. These analysts are forgetting that the most significant rebellion against the authority of the CCP was praised and to a large extent engineered by a wing of the party bureaucracy.

On May 18, the Daily pushed Gorbachev’s visit to a small item below the fold and ran six front-page stories on the student protest. Headlines blared: "One million from All Walks of life Demonstrate in Support of Hunger-Striking Students"; "Save the Students! Save the Children!" Other newspapers in different areas of the country joined the chorus. The Guangming Daily came out with seven front-page stories on the tumultuous events in Beijing, and proclaimed: "The conditions of the students and the future of the country touch the heart of every Chinese who has a conscience."

The Myth of Monolithism

American commentators were surprised that the Jiang Zemin-Clinton debate on the meaning of Tiananmen was broadcast live over the state-controlled television network. Their astonishment is equaled only by their ignorance: the Chinese media has been relatively open for some time. Since the Communist regime was installed in 1949, the media has been a battleground in the ceaseless factional conflicts within the Communist Party, and, to a certain extent, in the country at large.

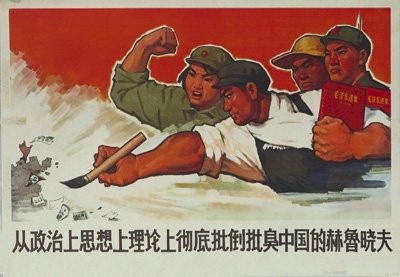

Mao’s "Hundred Flowers" campaign, followed by vicious repression, made ordinary Chinese wary of such "opening up." Yet the Cultural Revolution, a paroxysm of violence and collective madness, was ushered in by an article in the Chinese press, and orchestrated by an extensive media campaign that targeted the Communist Party itself as the seedbed of capitalism reborn.

Before the Tiananmen Square crackdown, the media was in the hands of reformers and was bold enough to broadcast party chieftain Zhao Ziyang’s indiscreet remarks to Gorbachev, during the latter’s visit, that Deng, although without any official post, was really at the helm. In 1989, at the height of the turmoil, the top leadership of the CCP met with the student rebels: the entire proceedings were broadcast nationwide by CCTV. It is as if, during the Chicago Democratic convention in 1968, Mayor Daley and Hubert Humphrey had agreed to "negotiate" with Mark Rudd, Bernadine Dohrn, and Abbie Hoffman while the cameras rolled.

The Chinese New Left

In understanding the politics and style of the Tiananmen Square protesters, the New Left analogy is useful. For these were leftists, in a Chinese context, in their ideology as well as in their provocative style.

From the very beginning, the student rebels marched into the Square singing the "Internationale," and toting portraits of Mao. According to Lee Feigon’s pro-student protester account of The Meaning of Tiananmen, the leaders of a prominent student group, who in alliance with city workers organized the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Trade Union, "hung big pictures of Mao in the tents they pitched on the square. They talked openly and boldly about the good old days of the Cultural Revolution. Mao, they felt, had the right ideas, although he sometimes used wrong tactics. Now they were determined to use what they considered the right ones." [p. 211]

Those tactics were as confrontational as any employed by any band of Yippies that ever marched through the streets of American cities in the sixties. The leadership of the student movement was fractious, and rarely spoke in a single voice, but the elected "Supreme Commander" of the Tiananmen Square encampment, Chai Lin, carried much moral authority, and it was largely through her influence that thousands of students failed to evacuate the Square even after word had reached them (reportedly from Deng Xiaoping’s son, Deng Pufang) that the tanks were rolling.

A Chinese Jonestown

That Chai Lin welcomed death, and that the actions of her and her hardcore followers amounted to a mass suicide, is clearly expressed by the "Supreme Commander" herself in an interview conducted in late May, just before the crackdown: "Some fellow students asked me what our plans are, what our demands will be in future. This made me feel sick at heart; I started out to tell them that what we were waiting for was actually the spilling of blood, for only when the government descends to the depths of depravity and decides to deal with us by slaughtering us, only when rivers of blood flow in the Square, will the eyes of our country’s people truly be opened." [Cited in Han Minzhu, ed., Cries for Democracy: Writings and Speeches from the 1989 Chinese Democracy Movement (Princeton Univ. Press, 1990), p. 327.]

Even as more reasonable student leaders, like Wu’er Kaxi, argued that the students, having made their point, should withdraw from the square and live to fight another day, Chai Lin, the "Supreme Commander," commanded her followers to stay and wait for martyrdom. Already embarked on a hunger strike that had weakened and even completely debilitated many students, they passively obeyed their fanatical "Commander." In style and spirit, the massacre at Tiananmen Square is closer to Jonestown than to a crusade for freedom.

Like the American New Left of the sixties, the Chinese New Left movement that reached its flaming apogee in Tiananmen Square employed radically self-dramatizing means to achieve egalitarian and "revolutionary" ends. They, too, held high the banner of Chairman Mao; like the Weathermen faction of SDS, Chai Lin and her hardcore supporters not only expected repression but openly hoped that their actions would provoke it.

Roots of the Movement

As Eric Margolis, foreign affairs editor of the Toronto Sun, so trenchantly put it, the Tiananmen Square "massacre has become a ’cause celebre‘ among fashionable leftists and literati, who have never forgiven China’s rulers for abandoning socialism."

This reaction to the policies of Deng and his successors was not limited to the West. It was reflected not only in the Maoist sympathies of some Chinese students, but also in the broad demands put forward by the student movement. Aside from vague assertions about the need for "democracy," the more concrete details of the students’ program were remarkably pedestrian. At the height of the reforms, with government subsidies to students cut to the bone, intellectuals saw their incomes stay stagnant or even decrease at a time when relatively uneducated peasants were going into business and following Deng’s maxim to get gloriously rich: while insisting on their right to march, and to free speech the students also demanded "more money for education and higher pay for intellectuals." [Feigon, p. 135]

A 1988 survey "showed that the average college graduate earned $9 per month less than those who had not gone to college," and this widely known fact energized much of the students’ revolutionary fervor. What Ludwig von Mises called "the anti-capitalistic mentality," so endemic among intellectuals, who feel underappreciated and undervalued by the market economy, was clearly at work here.

Chinese Race Riots

Another underreported aspect of the student movement, and the Tiananmen protest of `89 was the politically incorrect racial aspect. While Chinese students were forced to live 6 or 8 to a room no bigger than a closet, foreign students sponsored by the Chinese government, primarily from Africa, were given relatively luxurious quarters and good food, all gratis. Anti-African protests broke out in the city of Hehai, ending in violence. Shouting anti-black slogans the student militants rampaged through the Africans’ dormitories, roughed up all foreigners, and besieged local authorities. Campus protests soon spread to Shanghai, Beijing, and elsewhere.

Anti-foreign sentiment was a significant undercurrent of the Tiananmen Square rebellion. On April 19, militants from the encampment marched on the living quarters of the top Party leaders at the famous Zhongnanhai compound: screaming insults at Deng, they also yelled "Kill the foreigners!" As Lee Feigon, an eyewitness sympathetic to the students, relates: "The police, in fact, seemed remarkably tolerant, appearing unflustered by the constant jeering and screaming. Many who watched doubted that the American Secret Service would have reacted so genially if a similar mob were battering on the gates of the White House in the middle of the night. This was carried to an extreme at about 2:30 a.m. when the police tried to clear the crowd and some of them were pushed back onto a cluster of fallen bicycles. One tough picked up one of the bikes and smashed it over the head of one of the police. He was not arrested." [Ibid., p. 139.]

Deng’s Long March

At the height of the Cultural Revolution, a million Red Guards had answered Chairman Mao’s summons to assemble in Tiananmen Square and "make revolution": the result had been a decade of turmoil and a Great Leap Backward in terms of economic development. By the time Mao died, virtually all institutions of higher learning had been closed down, and in large parts of the country industrial production nearly ground to a halt. Agriculture was also seriously hampered: China could barely feed her starving millions.

Deng personally suffered during this ultra-leftist interregnum: not only was he stripped of his positions and banished to the countryside, where he served in a "work brigade," but he was denounced as "China’s number-two capitalist-roader" (Liu Shaochi being Number One). His son, Deng Pufang, was attacked by a mob of frenzied Red Guards and thrown out of a window at Beijing University: he was paralyzed from the waist down.

The Cultural Revolution

The "Gang of Four," led by Madame Mao, the Chairman’s depraved and vicious wife," directed a reign of terror at Deng and many other longtime CCP veterans. A ruthless egalitarianism was enforced, and everyone in a position of authority or tainted by expertise was ruthlessly "criticized" until they confessed in public to being "capitalist roaders." All material incentives were abolished, and instead central planners counted on ideological zeal to boost industrial production. Thousands of years of Chinese culture were expunged, as Red Guards smashed priceless artwork and looted ancient Buddhist monasteries, in a relentless campaign against the "ghosts and monsters" of the "feudal" past. Madame Mao, in her youth a movie actress of minor repute, took a special interest in "revolutionizing" culture. The traditional Chinese opera was banned, as a reactionary relic, and replaced by a series of "revolutionary" operas.

As the orgy of destruction reached its climax, Richard Nixon chose to make his rapprochement with the Beijing regime. The cementing of this alliance against the Soviet Union signaled by his famous trip to the People’s Republic. While Clinton was regaled with displays of traditional Chinese culture at its most elaborate, Nixon’s entertainment was confined to a performance of "The Red Detachment of Women," one of Madame Mao’s "revolutionary" ballets.

As British journalist James Pringle recalled, "Mao’s sour-faced wife . . . hosted Nixon at a rather grubby theatre for the performance, and he smiled as she told him that the face on a target that the people’s heroes were firing at was that of Chiang Kai-shek," the Nationalist Chinese dictator of Taiwan, who still claimed suzerainty over all China – and who, up until that moment, had been our staunch ally.

A Rightist Wind

Mao used the Red Guards to destroy his enemies in the Party, but in the end he balked at turning over power to his wife and her coterie. As the country descended into chaos, Mao pulled back: the Red Guards were told to return to their universities and workplaces. The army was called in to quell the ‘revolutionary" fervor of the Maoist mobs, and the "Cultural Revolution Group" that ran the Party’s propaganda machine was chastened by the Chairman if not yet silenced

With the ultra-leftists reined in, Mao called many of the purged "rightists" back into government service, Deng among them. Though the reformist group was reinstalled in the top leadership of the party by the rehabilitated Liu Shaochi, the hard-line Maoists were still a threat to any hope of reform. The hard-liners were still entrenched in many areas of the country, notably in Shanghai, Madame Mao’s base of operations and traditionally a leftist stronghold.

The Death of Zhou En Lai

When Zhou died, in 1976, an article appeared in a Shanghai newspaper accusing Zhou of having been a "capitalist-roader." The piece was widely interpreted as being a not-so-veiled attack on Deng. In late March, which is the time Chinese traditionally honor their dead ancestors, the Chinese people responded to the attacks by laying wreaths on public monuments honoring Zhou: 30 wreathes were hung in Tiananmen Square, and hundreds of thousands of demonstrators poured into the square.

After five days, during which the government was paralyzed by internal conflict, the police confronted the demonstrators; as many as one hundred were killed, and thousands arrested. Deng had reportedly been placed under house arrest even before the crackdown, and after the demonstrators were quashed he was once again purged from the leadership, relieved of all his positions in the party and the government, and sent into internal exile.

Deng Treatment

But not for long. Mao’s death, and the downfall of the Gang of Four at the hands of the army, soon returned Deng to power. Although he led China into a new era of modernization and economic development, with an annual growth rate of nearly 10 percent, the bitter legacy of the Cultural Revolution was still fresh in Deng’s mind, more than twenty years later, as the universities erupted once more. The man who had faced down Madame Mao and her fanatic Red Guards, and even replaced Mao as the great helmsman of the nation, was not about to turn the country over this latest bunch of self-proclaimed student revolutionaries.

Contrary to the myth of "Red China" as a monolithic political entity whose subjects march in lockstep with an all-powerful Communist regime, the history of the country since the sixties had been one of uninterrupted political turmoil. Deng, determined to build a prosperous China out of the ashes of Maoism, put a stop to it. When the students once again filled Tiananmen Square, carrying portraits of Mao, and calling for the overthrow of the government, he was determined that it would not happen again. In the context of Chinese politics and history since the sixties, the Tiananmen Square insurrection of `89 was a leftist, implicitly anti-capitalist reaction to Deng’s program of economic reform, albeit one aided and abetted by radical reformists in the Communist Party itself.

The New Evil Empire?

In terms of sheer scope and mendacity, the propaganda campaign unleashed in this country against China rivals anything cooked up by Madame Mao and her cohorts during the Cultural Revolution. While the Tiananmen square myth is emblematic of the grotesque fiction concocted by the China-bashers, their campaign to conjure a new Yellow Peril has concentrated on three major areas designed to appeal to the three major components of the anti-China coalition:

1) The Military "Threat" – The assertion that China represents a military threat to the United States is proof that no idea is so obviously erroneous that some alleged "expert" somewhere has not endorsed it. Unlike the US, China is cutting back on its "defense" spending: Chinese military expenditures were reduced by 25 percent during the mid-eighties, and since then the increases have fallen below the inflation rate. The three-million-man Peoples’ Liberation Army is half conscripts, equipped with hopelessly outdated weaponry, and burdened by mind-boggling logistics problems.

2) The hypocrisy and insincerity of the Republican warmongers in Congress who rail about Chinese nuclear missiles, supposedly aimed at American cities, was underscored by their response to the most substantial achievement of the Sino-American summit: the agreement by both parties to de-target their nukes. Everybody knows that they can be re-targeted in a matter of minutes, was the Republicans’ reply. But if that is so, then no agreement is worth anything – and we should go to war and be done with it. By this mad "logic," a nuclear first strike against Beijing is justified on the grounds that it would eliminate long-range missiles that could, at any moment, be retargeted at American cities.

Republicans accuse Clinton of selling militarily sensitive satellite technology to the Chinese government in exchange for a few hundred thousand dollars in campaign contributions. The irony is that the real use of this technology is to launch communications satellites, such as AsiaSat, which allows the growing number of Chinese satellite dishes aimed in its direction to bypass the state-controlled media and tune in to the worldwide buzz. In the name of anti-Communism, these new Cold Warriors are willing to throw away the most powerful weapon in the anti-Communist arsenal.

China and Christianity

3) The Religious Angle – Pat Robertson has descried the anti-China lobby gathering force among religious conservatives as "morally irresponsible and politically ignorant. Few things bring people together like a common enemy," he writes. "To some, China has done a masterful job of playing the villain. The China bashers prosper in direct mail and media campaigns, but they do not have the weight of righteousness on their side." [Wall Street Journal, June 30, 1998]

This nails the Sinophobes’ lobby for what it is: a cynical attempt to cash in on the gullibility of all too many conservatives, who are sincere in their anti-Communism but know next to nothing about China. Wiliiam McGurn, editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review, and for many years associated with the conservative National Review, said it best. While not arguing that Beijing has established freedom of religion, he writes: "When American critics declare that things are getting worse, it prompts the great unasked question: Compared with what?" The "criticism now leveled by American Christian activists seems less a snapshot of China in the late 1990s than a caricature drawn from the high days of Maoism a generation ago."

Christian churches were closed during the Cultural Revolution: Bibles were forbidden, all religious proselytizing was banned, and believers were often imprisoned, tortured, and killed. Today, government-sanctioned "patriotic" churches, including Catholics and the various Protestant denominations, function openly: Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network has aired its programs over state-run television. While there has been some resistance on the part of local Party officials to the cultural implications of China’s opening up to the West, these are isolated incidents that go against the national trend.

China’s long march toward capitalism and freedom is in danger of stalling: "capitalist-roaders" like Deng and his successors, have had to face not only domestic enemies who long to restore Maoism, but enemies abroad intent on putting obstacles in their path. A new Cold War, with China cast in the Soviet role, would put China, as well as much of the world, on an altogether different road.

NOTES IN THE MARGIN

You can check out my Twitter feed. But please note that my tweets are sometimes deliberately provocative, often made in jest, and largely consist of me thinking out loud.

I’ve written a couple of books, which you might want to peruse. Here is the link for buying the second edition of my 1993 book, Reclaiming the American Right: The Lost Legacy of the Conservative Movement, with an Introduction by Prof. George W. Carey, a Foreword by Patrick J. Buchanan, and critical essays by Scott Richert and David Gordon (ISI Books, 2008).

You can buy An Enemy of the State: The Life of Murray N. Rothbard (Prometheus Books, 2000), my biography of the great libertarian thinker, here.