After three years of stagnation, this past week saw clear steps towards peace in Ukraine. Trump and Putin spoke on the phone, and US and Russian negotiators met face to face in Saudi Arabia for the first time in years. Trump said explicitly that he was “okay” with Russia’s demand that Ukraine be denied membership in NATO, adding, “I’m just here to try and get peace. I don’t care so much about anything other than I want to stop having millions of people killed.” US Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, told NATO allies that “returning to Ukraine’s pre-2014 borders is an unrealistic objective,” acknowledging officially that this war will end similar to how Finland escaped World War 2, with what they proudly refer to as “defensive victory” (torjuntavoitto), in which they lost territory, but retained their independence rather than being returned to the unwelcoming bosom of Mother Russia.

As I write this from Helsinki, where I have been involved in genetics research for the past 35 years, I have been shocked by their reaction to the Ukraine war, which strikes me as collective hysteria stemming from their complex relationship with their neighbor to the East. In 2017, only 19% of Finns supported NATO membership, but by 2022, that number rose to 78%, as Finns feared they might be the next target of Russian aggression.

Finland faced an existential crisis when the tide of World War II turned, and Soviet forces advanced in the East, just as Russian forces continue their steady advance in Eastern Ukraine today. It now seems clear that Ukraine must soon accept the reality that a Finnish-style “defensive victory” may be the only victory possible. While that might seem bleak to Ukrainians as it did to Finns in 1944, let us explore how Finland’s historical example could serve as a role model for how to achieve a bright and prosperous future for postwar Ukraine.

The Template for Ukraine’s Struggle

For many centuries, Finland and Ukraine have been borderlands caught between great empires, subjected to the ambitions of dominant neighbors. Ruled for centuries by Catholic Western empires, they later fell to the ascendant Russian Empire. Both exploited moments of Russian weakness to achieve independence, Finland in 1917 and Ukraine in 1991, after which Russia used its military might to advance its borders Westward. Finland’s conflict with Russia ended 80 years ago, while Ukraine’s is ongoing today. Let’s examine that history in detail to see what lessons it holds for Ukraine’s future.

Foreign Conquest by Catholic Western Empires

Finland came under Swedish rule in the 12th and 13th centuries, when Sweden launched the Northern Crusades to expand Catholic influence into pagan Baltic and Finnic lands. This conquest led to Finland’s incorporation into the Kingdom of Sweden. Swedish became the language of government, education, and elite society, and Finns were relegated to a linguistic and political underclass.

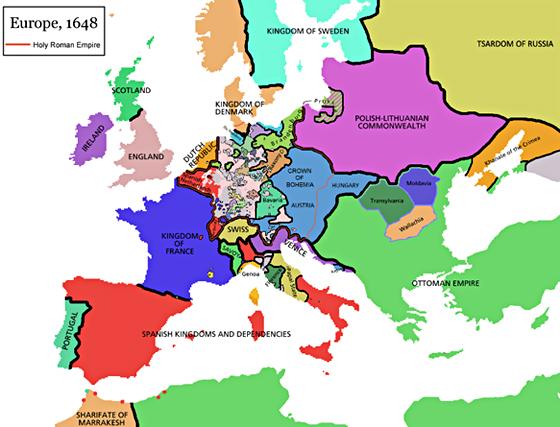

Ukraine experienced a parallel fate under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which controlled most of modern Ukraine from the 16th to 18th centuries. Much like Sweden, Poland sought to expand Catholic influence in the East, suppressing Ukrainian political identity and enforcing Polish as the language of governance.

In both cases, these Catholic rulers attempted to reshape the identities of these lands, but local languages and cultures endured, setting the stage for later struggles for independence.

Absorption into the Russian Empire

In 1809, Sweden lost Finland to Russia in the Finnish War. Under the Treaty of Fredrikshamn, the Grand Duchy of Finland was granted internal autonomy, retaining Swedish-style governance and laws. To detach Finland from Swedish influence, the capital was moved East to Helsinki in 1812, ostensibly to help promote Finnish identity.

In 1667, following a 13-year conflict between Poland and Russia, the Treaty of Andrusovo divided Ukrainian lands, giving those east of the Dnieper River to Russia. The semi-autonomous Cossack Hetmanate was abolished in 1764, and by 1795, with the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, most of contemporary Ukraine fell to Catherine II.

While both Finland and Ukraine initially retained some local governance, Russia ultimately pursued a policy of centralization and Russification, leading to the suppression of their national identities.

The Rise of National Identity and Russification

In Finland, the Fennomania movement promoted Finnish linguistic and cultural recognition, and in 1863, Finnish was granted equal status with Swedish, leading to a flourishing of Finnish literature and nationalism. However, after Alexander II was assassinated in 1881, Russia reversed course, imposing strict Russification policies, limiting Finnish language rights and expanding direct imperial control.

Ukraine followed a similar trajectory. The early 19th century saw the rise of a Ukrainian literary movement spearheaded by Taras Shevchenko, whose poetry channeled Ukrainian historical, cultural and nationalist themes. However, rising nationalism led Alexander II to issue the Ems Ukaz in 1876, banning Ukrainian-language publications, education, and public performances. As in Finland, Russification policies aimed to erase Ukrainian identity.

Seizing Independence

Both Finland and Ukraine achieved independence not by victory on the battlefield, but by exploiting moments of Russian imperial collapse.

Finland declared independence on December 6, 1917, as the Russian Revolution plunged the empire into chaos. The Bolsheviks recognized Finnish sovereignty on December 31, along the administrative borders of the Grand Duchy, which had been drawn without concerns about national security. The proximity of Leningrad to this border created a strategic vulnerability that the USSR later cited as justification for the Winter War in 1939.

Ukraine declared independence on August 24, 1991, as the Soviet Union was beginning to collapse. When it dissolved on December 26, 1991, the world recognized domestic inter-republican borders as international borders between the newly independent states, leaving Crimea and Donbass inside Ukraine, despite their ethnic, historical, and cultural ties to Russia, setting the stage for future conflict.

War with Russia I

On November 30, 1939, Soviet troops attacked Finland, demanding territorial concessions to bolster the defense of Leningrad from potential Nazi attacks. Despite being vastly outnumbered, the Finnish military mounted a fierce resistance, inflicting roughly ten times more casualties than they suffered. Western nations, including Britain and France, sent weapons and financial support but did not intervene directly – “Finns appreciated foreign aid, but did not receive enough of it.”

After three and a half months, Finland signed the Moscow Peace Treaty on March 13, 1940, ceding roughly 10% of their territory in Karelia, Salla, and Kalastajasaarento. Finland remained independent, but the situation remained unstable, as Finns wanted their land back.

This parallels Ukraine’s situation in 2014, when subsequent to a Western-led coup d’état in Kiev against pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovich, predominantly Russophone Crimea, voted overwhelmingly to secede from Ukraine and join the Russian Federation. Shortly thereafter, pro-Russian separatists in Donbass followedsuit, in response to new restrictions on minority language rights, and a bloody war of secession broke out.

After almost a year of fighting, on February 12, 2015, the Minsk II protocol was signed, agreeing to a ceasefire. Like Finland in 1940, Ukraine lost control over about a bit less than 10% of its territory but remained sovereign, as Western nations supplied only “nonlethal aid,” avoiding conflict with Russia.

War With Russia II

When Nazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, Finland joined their offensive, calling it the “Jatkosota” (Continuation War), hoping to regain lost territories. Finnish forces initially succeeded, reclaiming Karelia and advancing deep into Soviet territory. However, as the Red Army regrouped, Finland found itself on the defensive. By 1944, Finland faced a no-win situation and signed the Moscow Armistice. In what Finns proudly refer to as “Torjuntavoitto” (Defensive Victory), Finland retained its independence, unlike the Baltic States, but was forced to relinquish 12% of their land, including parts of Karelia, Salla, and Petsamo – indicated in red on the map.

In 2022, with NATO openly speaking about admitting Ukraine, Russia launched a “special military operation” to secure the separatist regions in Donbass and Crimea, as well as Zaporizhia and Kherson, to provide strategic control of a land bridge to Crimea and its power and water supplies. By 2025, Russia had managed to occupy the vast majority of these territories (shown with diagonal lines on the map). Like Finland in 1944, Ukraine has fought valiantly but is confronting a stronger, larger enemy that cannot be defeated outright. Continuing the war indefinitely will likely result in more territorial losses, further depopulation, and economic devastation.

Finland’s choice was not just about ending the war; it was about securing its future. With its military options exhausted and no realistic path to reclaiming lost land, Finland’s leaders understood that national survival depended not on continued fighting but on economic transformation. In the decades that followed, Finland proved that military victory is not the only kind of victory. Ukraine now stands at the same crossroads. Just as Finland pivoted from war to rebuilding, Ukraine must now choose whether it will do the same.

A Model for Ukraine

Finland’s post-war success was not an inevitability, it came from difficult strategic decisions made despite intense public anger and nationalist resentment. Finland emerged from World War II in a dire position, owing war debts of $300 million in reparations to the Soviet Union. Rather than dwelling on what was lost, they focused on economic survival, ensuring that national strength would come from industrial development. Within a decade, Finland had transformed itself into a modern economy, proving that a country’s future is determined not only by battlefield outcomes but also by its ability to adapt.

Initially, the reparations seemed like an insurmountable burden, requiring payment in industrial goods rather than cash. This cloud had a silver lining, however, as it forced Finland to industrialize rapidly. The Finnish economy, once heavily agrarian, was forced to suddenly expand its shipbuilding, metalworking, and machinery industries to meet Soviet demands. By the time reparations were completed in 1952, Finland had developed a robust industrial base that fueled decades of economic growth, allowing its integration into global markets. What was meant to weaken Finland instead became a foundation for its long-term economic success.

Politically, Finland had to navigate a careful path of neutrality. As stipulated in the 1948 Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance, Finland remained outside NATO, maintaining military independence. This neutrality allowed Finland to avoid the fate of Warsaw Pact nations, which fell under Soviet control, while also preventing unnecessary entanglements in Cold War conflicts. Unlike many of its neighbors, Finland was able to focus entirely on its development rather than being drawn into great-power struggles.

Finland’s ability to flourish as an economic bridge between East and West ensured long-term stability. It developed favorable economic relations with the Soviet Union, exporting industrial goods while importing cheap raw materials. At the same time, Finland integrated with Western markets, becoming an associate member of the European Free Trade Association in 1961 and securing a free trade agreement with the European Economic Community in 1971.

By the 1980s, Finland had one of the most advanced economies in Europe, with strong technology, telecommunications, and manufacturing sectors. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Finland was fully prepared to transition into the West, joining the European Union in 1995 without major economic disruption.

Finland’s economic success was not just a side-effect of Soviet war reparations; it was the result of smart policy choices. By remaining neutral, Finland could trade with the Soviet bloc and the West. It embraced a mix of state-driven industrial growth and market-oriented policies, ensuring long-term economic competitiveness. Without these deliberate choices, Finland’s early industrialization might have been a short-term adjustment rather than a lasting economic transformation.

Finland’s post-war strategy offers a clear roadmap for Ukraine. Finland lost Karelia but gained prosperity – proving that territorial concessions do not necessarily equate to national decline. Rather than obsessing over lost territory, Finland focused on economic growth, ensuring that it would be strong enough to decide its future. Its neutrality protected its independence, while its engagement with both East and West provided economic stability.

Finland’s success required a painful level of strategic realism, clashing with nationalist emotions at the time. Today that same realism is absent from Finnish discussions about Ukraine. Instead of recognizing that strategic compromise saved their nation, Finns are allowing historical memory to cloud their judgment. The fear and trauma of past Russian aggression are driving Finland toward self-destructive policies, just as they push Finns to demand that Ukraine fight to the bitter end.

When History Becomes a Trap

Finland, more than any other nation, should understand why Ukraine must now accept reality. But rather than advising them to follow their example and sacrifice territory to retain sovereignty, the modern Finns believe Ukraine should chase the kind of total victory that Finland was unable to achieve. A recent poll found that only 10% of Finns believe peace in Ukraine should involve territorial concessions, ignoring military and political realities – Ukraine, like Finland in 1944, cannot achieve total victory against a superior Russian force.

Instead, Finns are acting out their historical frustrations. They wish Western powers had intervened in the 1940s, and now they desperately want Ukraine to succeed where Finland could not. But this is fantasy. Ukraine, like Finland, must accept reality and take the deal before its position worsens.

Their strong stance is now costing Finland dearly. Strict enforcement of economic sanctions and the sealing of the 1343 km land border with Russia have backfired, devastating Finnish industries while Russia’s economy continues to grow through increased BRICS trade. Finnish exports to Russia have collapsed from over 2,000 firms exporting to Russia in 2019 to just 100 by late 2023. Finnish GDP is contracting, debt has risen to 81% of GDP, and unemployment has climbed to 12%. The airline industry has been wrecked by lost access to Russian airspace, and the bottom has fallen out of Helsinki’s tourist industry with over a million fewer annual overnight stays from Asian and Russian visitors. And restaurant industries have seen a 70% rise in bankruptcies, as the once vibrant Helsinki nightlife has all but disappeared. Finland’s past success was built on pragmatism, trading with both East and West. Today, by enforcing self-destructive sanctions, it is abandoning the very strategy that once made it strong.

Finland’s reaction is driven by irrational fears of a Russian invasion. Even though Russia is struggling to defeat Ukraine and Finland is now under NATO protection, 85% of Finns still believe Russia poses an imminent military threat. This paranoia has reshaped Finland’s foreign policy, pushing it toward hardline positions that are neither rational nor sustainable.

The tragic irony is that Finland is rejecting the very strategy for Ukraine that ensured its survival. If Finland had followed its advice to Ukraine, to never compromise and fight to the last man, it would have ceased to exist as an independent state. Instead, Finland chose a defensive victory, safeguarded its sovereignty, and became prosperous. Ukraine should do the same, and fast.

Finland Is the Only Realistic Path for Ukraine

Peace talks have begun in Saudi Arabia, and Trump’s administration has made it clear: Ukraine will have to accept the loss of territory and remain neutral. This outcome is not an abandonment of Ukraine; it is a recognition of reality. While insisting Ukraine must stay out of NATO, and that no NATO troops be stationed in Ukraine going forward, Russia agreed that Ukraine is free to pursue membership in the European Union, much as Finland pursued Western economic engagement in the mid-20th century.

US National Security Adviser Mike Waltz recently laid out four tenets of any peace agreement: “Number one, it has to be a permanent end to the war, not a temporary end to the war. Number two, this can’t be ended on the battlefield. This has turned into a World War I-style meat grinder of human beings. Number three, I talked about how the structure of our aid has to change. Then number four, we’re talking about economic integration going forward as the best arbiter of peace.” The only solution that meets these conditions is a Finnish-style defensive victory. The alternative is a permanently frozen conflict akin to those in Abkhazia, Kosovo, and Western Sahara, an outcome that benefits no one.

Once a peace deal is in place, the US, Ukraine and Europe must immediately end sanctions and resume trade with Russia. Finland, whose economy has been crippled, stands to gain the most from reopening economic ties. Overflight rights, energy imports, and financial reintegration will not just help Russia; they will help Finland and the rest of Europe to climb out of the economic hole it has dug for itself. In Riyadh, Russia and the US even discussed “joint projects in the Arctic,” related to both minerals and shipping lanes, as one avenue to begin the reintegration of Russia into the Western economy.

Today, Finland is prosperous and free today because, in 1944, its leaders made the right choice. Ukraine must follow Finland’s example, not just in history but in strategy. A defensive victory secured Finland’s future. Chasing an impossible dream will only lead to further ruin.

Joseph D. Terwilliger is Professor of Neurobiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, where his research focuses on natural experiments in human genetic epidemiology. He is also active in science and sports diplomacy, having taught genetics at the Pyongyang University of Science and Technology, and accompanied Dennis Rodman on six “basketball diplomacy” trips to Asia since 2013.