Last month, I completed work on my first film, writing and directing a documentary titled Atomic Cover-up. Below you can watch via a link four brief clips. The story for me began, however, thirty-eight years ago this month. That day also helped set me on the path to spending four weeks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki soon after, and subsequently writing three books on the subject (including one to be published in July), hundreds of articles, and a lifelong engagement with political and ethical issues surrounding nuclear warfare.

In June 1982, the grassroots antinuclear movement in the U.S. (and much of the world) was cresting. The June 12th march and rally in New York City would draw well over half a million protesters, with some observers calling it the largest such gathering in the country’s history. Many new films with nuclear themes suddenly appeared, including the popular Atomic Cafe.

The Atomic Cafe (1982) – Re-Release Trailer

As someone who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s, I had experienced the terror of the most dangerous years of the nuclear arms race, but I had never attended an “anti-bomb” protest. My knowledge of the debate surrounding the dropping of two atomic bombs over Japan in 1945 was only skin-deep.

But one day in June 1982, I took notice when the Japan Society in New York announced it would screen the first movie drawing on footage shot in vivid color in Hiroshima and Nagasaki by an elite American military team, then suppressed for decades by the US government. One of the US Army officers who was part of that team would discuss the film and its suppression for the first time. I was a member of the Japan Society–they had even arranged my recent interview with film director Akira Kurosawa–and always loved a good “cover-up.” So I attended the event a few days later.

The film, produced in Japan, was called Prophecy. Someone connected with it introduced former Army lieutenant Herbert Sussan, who went on to a long career as a producer/director in the emerging television industry. He described being recruited near the end of 1945 from the Army’s famous wartime film studio in Hollywood (where he had met Ronald Reagan, among others) to join a major US Strategic Bombing Survey project to shoot the first and only color footage documenting the destruction of Japanese cities from the air during the war. It seemed to offer a free, triumphant, trip for the young man until the crew arrived by train at their first stop: Nagasaki. He would be haunted by what he saw there, and then in Hiroshima, for the rest of his life.

The Prophecy (Part 1 of 6)

I suppose, no doubt to a lesser degree, I could say that I would be haunted by his words, and the film we would see, for the rest of my life.

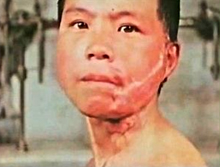

Sussan described filming, in blazing color–still rarely used by documentarians at the time–the badly injured, burned or radiation-plagued patients in hospitals. The cameraman was often Akira “Harry” Mimura, from the major Toho studio who had shot Kurosawa’s first film, Sanshiro Sugata, and also worked in Hollywood.

Hiroshima after the bombing, 1945

Americans back home, to this point, he pointed out, had only been allowed to see grainy, black and white images of rubble in the atomic cities, never the victims, who were mainly women, elderly men and children. The US had also seized, or banned publication in Japan of photographs of bombing victims taken by Japanese, a ban that remained throughout the Occupation years to 1952.

When he returned to New York after filming in numerous other bomb-ravaged Japanese cities, Sussan was determined to show the world what he had experienced, hoping that this might halt the building of new and bigger weapons and prevent a dangerous nuclear arms race with the Russians.

Instead, he found that all of the footage had been classified top secret and buried by the US military. Some of it would eventually be used in training films, but none of it was shown to the public. The color images were just too revealing not only of unfathomable destruction of buildings, but above all the long-lasting damage to human bodies.

Seized at the same time by the US and hidden for the next quarter of a century was all of the searing black and white footage shot earlier by the leading Japanese newsreel company, Nippon Eiga Sha.

Sussan tried for twenty years to find and make use of his footage–Americans still had not been exposed to color images of any kind from Hiroshima and Nagasaki–but he got nowhere, even after personally approaching everyone from famed newsman Edward R. Murrow to former President Harry S. Truman.

Frame from color footage that Sussan saw at photo exhibit

Finally, he would, almost by accident, play a central role in the footage becoming known to the world. Around 1979 he attended an exhibit of photos from the atomic cities at the United Nations near his apartment. To his dismay, he spotted several color enlargements of frames from the footage his team had shot in 1946.. He said to a Japanese man, Iwakura Tsotumu, who had helped arrange the exhibit, something to the effect, “I shot the footage this photo is taken from.”

Imagine Iwakura’s surprise. Iwakura did some digging at the National Archives in Washington and discovered that the color footage had been declassified, very quietly, a few years earlier. If no one knew about this, it was just the same as still being classified.

Iwakura went back to Japan and launched what became known as the “10 Feet Movement,” a grassroots project that encouraged people (including school kids) to raise and contribute funds to buy back copies of all of the color footage in increments of ten feet. When they reached their goal in 1980, he made the footage available to Japanese filmmakers, who soon completed two documentaries, with more in the works.

The creators of the film that I saw, Prophecy, directed by Hani Susumi, were able to track down some of the survivors shown in the 1946 footage and then contrast the badly-scarred images of them in 1946 with images from interviews with them from the early 1980s. Soon Americans started making use of the color footage–although only in brief passages–in their own films.

Sussan was gravely ill (one of his doctors would tell him it was at least possible that his lymphoma stemmed from radiation exposure in 1946). But my interest had been sparked by listening to him and watching Prophecy. Later in 1982, when I became the editor of the leading American magazine for the anti-nuclear movement, Nuclear Times, the first feature I assigned was on Herbert Sussan. I joined in the interview and became a friend.

I also tracked down in California the man who led the US filming project, Lt. Col. Daniel A. McGovern. On why the footage was suppressed, McGovern informed me that officials and the military “were fearful because of the horror it contained. …because it showed effects on men, women and children…They didn’t want that material out because they were working on new nuclear weapons.” He also sent to me dozens of pages of formerly secret documents from his files, including the original military orders to shoot the footage, his attempts to use the Japanese and/or American footage in films for the public, and the official orders denying that, plus logs of all the classified footage.

I would also talk with Erik Barnouw, the legendary writer on documentary films who in 1970 had created the first film to make use of the long-suppressed black and white Nippon Eiga Sha footage, Hiroshima-Nagasaki 1945. It aired over public television in the US at its full sixteen-minute length, and drew wide attention, although at least one local station refused to air it.

Hiroshima-Nagasaki 1945: The Original Footage

Aiming to gain firsthand experience, I secured a journalism grant via Akiba Tadatoshi (much later the mayor of Hiroshima) to spend a month in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, meeting among others some of those filmed by Sussan and McGovern. Then I wrote articles on various aspects of that trip for The New York Times and Washington Post, among others, and dozens of articles about the atomic bombings for numerous other outlets. I would even interview Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the Enola Gay, which deposited the bomb over Hiroshima, and meet his counterpart on the Nagasaki mission, Charles Sweeney.

A decade later, I penned a small section on the color footage in my book with Robert Jay Lifton, Hiroshima in America. A few years later, I wrote a book about the saga of the footage, Atomic Cover-up, which was excerpted here at The Asia-Pacific Journal.

It even plays a role in my new book to be published next month, The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood–and America–Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, on the MGM docudrama of that name, also shot in 1946. The MGM movie was directly inspired by warnings from the atomic scientists against building bigger bombs and an arms race with the Russians, but was soon transformed into falsified, pro-bomb propaganda under pressure from the White House and the military. Any mention of Nagasaki, for example, was left on the cutting room floor.

Finally, last year, I set out to fulfill the vision I had, decades ago, of paying tribute to those who shot both the Japanese newsreel and US military footage in 1945-1946. I arranged for the first super-high definition transfers of the Japanese footage and several reels of the color footage from the National Archives. I also obtained relevant portions of books by or about several of the cameramen and producers of the Japanese footage, and the memoir of Harry Mimura, and had key sections translated from the Japanese. (Abe Markus Nornes, the leading American authority on the Japanese footage, served as an advisor.)

Starting in March, working remotely with an editor in New York, I directed a subtle, perhaps artful, 47-minute documentary, with an original musical score, also titled Atomic Cover-up. It’s told completely through the once-buried Nippon Eiga Sha and American footage, and via the first-person accounts of those who shot or produced it in voice-overs.

I am happy to provide four brief excerpts:

The first features Lt. McGovern describing his arrival in Nagasaki and Hiroshima for the first time, accompanied by the striking color images.

The second reveals the seizure of the Nippon Eiga Sha footage by the US occupation authorities and how the filmmakers responded–by hiding a print in the ceiling.

The third finds Lt. Sussan paying tribute to the doctors and nurses at the partly destroyed Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima, which has particular resonance today as health workers there and throughout the world cope with the still-horrendous Covid-19 crisis.

And the final one documents the beginning of Sussan’s attempts to locate the footage by approaching everyone from Truman to Robert F. Kennedy.

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including most recently The Tunnels: Escapes Under the Berlin Wall (Crown) and The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood–and America–Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

The original source of this article is The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus (APJJF). Copyright © Greg Mitchell, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 2020. All images in this article are from APJJF.