This Tuesday will be the 64th anniversary of a fateful day for our lives.

A day in November. A day to remember.

On Nov. 29, 1947, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted, by 33 votes against 13 (with 10 abstentions), the Palestine Partition Plan.

This event has become a subject of endless debates, misinterpretations, and outright falsifications. It may be worthwhile to peel away the myths and see it as it was.

By the end of 1947, there were in the country — then officially named Palestine — about 1.2 million Arabs and 635,000 Jews. The gap between the two population groups had turned into an abyss. Though geographically intertwined, they lived on two different planets. With very few exceptions, they considered each other mortal enemies.

This was the reality that the U.N. commission charged with proposing a solution found on the ground when it visited the country.

One of the great moments of my life is connected with this UNSCOP (United Nations Special Committee on Palestine). On the Carmel mountain chain, near kibbutz Daliah, I was attending the annual folk dance festival. Folk dances played a major role in the new Hebrew culture we were consciously striving to create. Most of these dances were somewhat contrived, even artificial, like many of our efforts, but they reflected the will to create something new, fresh, rooted in the country, entirely different from the Jewish culture of our parents. Some of us spoke about a new “Hebrew nation.”

In a huge natural amphitheater, under a canopy of twinkling summer stars, tens of thousands of young people, boys and girls, had gathered to cheer on the many amateur groups performing on the stage. It was a joyous affair, imbued with camaraderie, radiating feelings of strength, and self-confidence.

Not one of us could have guessed that within a few months we would meet again in the fields of a deadly war.

In the middle of the performance, an excited voice announced on the loudspeaker that several members of UNSCOP had come to visit. As one, the huge crowd stood up and started to sing the national anthem, “Hatikvah” (“the Hope”). I never liked this song very much, but at that moment it sounded like a fervent prayer, filling the space, rebounding from the hills of the Carmel. I suppose that almost all of the 6,000 Jewish youngsters who gave their lives in the war were assembled for the last time on that evening, singing with profound emotion.

It was in this atmosphere that the members of UNSCOP, representing many different nations, had to find a solution.

As everybody knows, the commission adopted a plan to partition Palestine between an independent “Arab” and an independent “Jewish” state. But that is not the whole story.

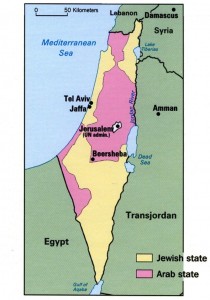

Looking at the map of the 1947 partition resolution, one must wonder at the borders. They resemble a puzzle, with Arab pieces and Jewish pieces put together in an impossible patchwork, with Jerusalem and Bethlehem as a separate unit. The borders look crazy. Both states would have been totally indefensible.

The explanation is that the committee did not really envision two totally independent and separate states. The plan explicitly included an economic union. That would have necessitated a very close relationship between the two political entities, something akin to a federation, with open borders and free movement of people and goods. Without it, the borders would have been impossible.

That was a very optimistic scenario. Immediately after the committee’s plan was adopted by the General Assembly, after much cajoling by the Zionist leadership, war broke out with sporadic Arab attacks on Jewish traffic on the vital roads.

When the first shot was fired, the partition plan was dead. The foundation, on which the whole edifice rested, broke apart. No open borders, no economic union, no chance for a union of any kind. Only abyssal, deadly enmity.

The partition plan would never have been adopted in the first place if it had not been preceded by a historical event that seemed at the time beyond belief.

The Soviet delegate to the U.N., Andrei Gromyko, suddenly made what can only be described as a fiery Zionist speech. He contended that after the terrible suffering of the Jews in the Holocaust, they deserved a state of their own.

To appreciate the utter amazement with which this speech was received, one must remember that until that very moment, Communists and Zionists had been irreconcilable foes. It was not only a clash of ideologies but also a family affair. In czarist Russia, Jews were persecuted by an anti-Semitic government, and young Jews, both male and female, were in the vanguard of all the revolutionary movements.

An idealistic young Jew had the choice between joining the Bolsheviks, the social-democratic Jewish Bund, or the Zionists. The competition was fierce and engendered intense mutual hatred. Later, in the Soviet Union, Zionists were mercilessly persecuted. In Palestine, local Communists, Jewish and Arab, were accused of collaborating with the Arab militants who attacked Jewish neighborhoods.

What had brought about this sudden change in Soviet policy? Stalin did not turn from an anti-Semite into a philo-Semite. Far from it. But he was a pragmatist. It was the era of medium-range missiles, which threatened Soviet territory from all sides. Palestine was in practice a British colony and could easily have become a Western missile base, threatening Odessa and beyond. Better a Jewish and an Arab state than that.

In the following war, almost all my weapons came from the Soviet bloc, mainly from Czechoslovakia. The Soviet Union recognized Israel de jure long before the United States.

The end of this unnatural honeymoon came in the early Fifties, when David Ben-Gurion decided to turn Israel into an inseparable part of the Western bloc. At the same time, Stalin recognized the importance of the new pan-Arab nationalism of Gamal Abd-al-Nasser and decided to ride on that wave. His paranoid anti-Semitism came again to the fore. All over Eastern Europe, Communist veterans were executed as Zionist-imperialist-Trotskyite spies, and his Jewish doctors were accused of attempting to poison him. (Luckily for them, Stalin died just in time and they were saved.)

Today, the partition resolution is remembered in Israel mainly because of two words: “Jewish state.”

No one in Israel wants to be reminded of the borders of 1947, which gave the Jewish minority in Palestine “only” 55 percent of the country. (Though half of this consisted of the Negev desert, most of which is almost empty even now.) Nor do Jewish Israelis like to be reminded that almost half the population of the territory allotted to them was Arab.

At the time, the U.N. resolution was accepted by the Jewish population with overflowing enthusiasm. The photos of the people dancing in the streets of Tel Aviv belong to this day, and not — as is often falsely claimed — to the day the state of Israel was officially founded. (At that time we were in middle of a bloody war, and nobody was in the mood for dancing.)

We know now that Ben-Gurion did not dream of accepting the partition-plan borders, much less the Arab population within them. The famous army “Plan Dalet” early in the war was a strategic necessity, but it was also a solution to the two problems: it added to Israel another 22 percent of the country, and it drove the Arab population out. Only a small remnant of the Arab population remained — and by now it has grown to 1.5 million.

But all that is history. What concerned the future are the words “Jewish state.” Israeli rightists, who abhor the partition resolution in any other context, insist that it provides the legal basis for Israel’s right to be recognized as a “Jewish state” — meaning in practice, that the state belongs to all the Jews around the world, but not to its Arab citizens, whose families have been living here for at least 13 centuries, if not far longer (depends who does the counting).

But the U.N. used the word “Jewish” only for lack of any other definition. During the British Mandate, the two peoples in the country were called in English “Jews” and “Arabs.” But we ourselves spoke about a “Hebrew” state (medina Ivrit). In newspaper clippings of the time, only this term can be seen. People of my age-group remember dozens of demonstrations in which we invariably chanted “Free immigration — Hebrew state.” The sound of it still rings in our ears.

The U.N. did not deal with the ideological makeup of the future states. It certainly assumed that they would be democratic, belonging to all their inhabitants. Otherwise they would hardly have drawn borders that left a substantial Arab population in the “Jewish” state.

Israel’s declaration of independence bases itself on the U.N. resolution. The relevant sentence reads “and on the strength of the resolution of the United Nations General Assembly, [we] hereby declare the establishment of the Jewish State in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.”

The ultra-rightists who now dominate the Knesset want to use these words as a pretext for replacing democracy with a doctrine of Jewish nationalist-religious supremacy. A former Shin Bet chief and present Kadima Party MK has submitted a bill that would abolish the equality of the two terms “Jewish” and “democratic” in the official legal doctrine and state clearly that the “Jewishness” of the state has precedence over its “democratic” character. This would deprive Arab citizens of any remnant of equality. (At the last moment, in face of the public reaction, the Kadima Party compelled him to withdraw the bill.)

The 1947 partition plan was an exceptionally intelligent document. Its details are obsolete now, but its basic idea is as relevant today as it was 64 years ago: two nations are living in this country. They cannot live together in one state without a continuous civil war. They can live together in two states. The two states must establish close ties between each other.

Ben-Gurion was determined to prevent the founding of the Arab Palestinian state, and with the help of King Abdullah of Transjordan he succeeded in this. All his successors, with the possible exception of Yitzhak Rabin, have followed this line, now more than ever. We have paid — and are still paying — a heavy price for this folly.

On the 64th anniversary of this historic event, we must go back to its basic principle: Israel and Palestine, two states for two peoples.