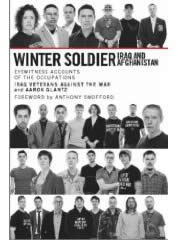

The following is an excerpt from Winter Soldier Iraq and Afghanistan: Eyewitness Accounts of the Occupations by Iraq Veterans Against the War and Aaron Glantz. From March 13-16, hundreds of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans gathered in Silver Spring, Md., to testify about atrocities they had personally committed or witnessed while deployed. Among those who testified was former Marine Corps Pfc. Vincent Emanuele of Chesterton, Ind. He served in Iraq in 2003 and 2005.

The following is an excerpt from Winter Soldier Iraq and Afghanistan: Eyewitness Accounts of the Occupations by Iraq Veterans Against the War and Aaron Glantz. From March 13-16, hundreds of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans gathered in Silver Spring, Md., to testify about atrocities they had personally committed or witnessed while deployed. Among those who testified was former Marine Corps Pfc. Vincent Emanuele of Chesterton, Ind. He served in Iraq in 2003 and 2005.

An act that took place quite often in Iraq was taking pot shots at cars that drove by. This was quite easy for most Marines to get away with because our rules of engagement stated that the town of al-Qaim had already been forewarned and knew to pull their cars to a complete stop when approaching a United States convoy. Of course, the consequences of such actions pose a huge problem for those of us who patrol the streets every day. This was not the best way to become friendlier with an already hostile local population. This was not an isolated incident, and it took place for most of our eight-month deployment.

We were sent out on a mission to blow up a bridge that was supposedly being used to transport weapons across the Euphrates, and we were ambushed. We were forced to return fire in order to make our way out of the city. This incident took place in the middle of the day, and most of those who were engaging us were not in clear view. Many hid in local houses and businesses and were part of the local population themselves, once again making it very hard to determine who was shooting from where and where exactly to return fire. This led to our squad shooting at everything and anything, i.e., properties, cars, people, in order to push through the town. I fired most of my magazines into the town, but not once did I clearly identify the targets that I was shooting at.

We were sent out on a mission to blow up a bridge that was supposedly being used to transport weapons across the Euphrates, and we were ambushed. We were forced to return fire in order to make our way out of the city. This incident took place in the middle of the day, and most of those who were engaging us were not in clear view. Many hid in local houses and businesses and were part of the local population themselves, once again making it very hard to determine who was shooting from where and where exactly to return fire. This led to our squad shooting at everything and anything, i.e., properties, cars, people, in order to push through the town. I fired most of my magazines into the town, but not once did I clearly identify the targets that I was shooting at.

Once we were taking rocket fire from a town, and a member of our squad mistakenly identified a tire shop as being the place where the rocket fire came from. Sure enough, we mortared the shop. This was one of the only times we actually had the chance to investigate what we had done and to talk to the people we had directly affected. Luckily, the family who owned the shop was still alive. However, we were not able to compensate the family, nor were we able to explain how it was he could rebuild his livelihood. This was not an isolated incident, and it took place over the course of our eight-month deployment.

Another task our platoon took on was transporting prisoners from our base back to the desert. The reason I say the desert and not their town is because that is exactly where we would drop them off, in the middle of nowhere. Now, most of these men had obviously been deemed innocent, or else they would have been moved to a more permanent prison and not released back into the population. We took it upon ourselves to punch, kick, butt-stroke, or generally harass these prisoners. Then, we would take them to the middle of the desert, throw them out of the back of our Humvees while continually kicking, punching, and at times throwing softball-sized rocks at their backs as they ran away from our convoy. Once again, this is not an isolated incident, and this took place over the duration of our eight-month deployment.

The last and possibly the most disturbing of what took place in Iraq was the mishandling of the dead. On several occasions, our convoy came across bodies that had been decapitated and were lying on the side of the road. When encountering these bodies, standard procedure was to run over the corpses, sometimes even stopping and taking pictures with these bodies, which was also standard practice whenever we encountered the dead. On one specific occasion, I had shot a man in the back of the head after we saw him planting an IED device; we pulled his body out of the ditch he was laying in and left it to rot in the field. We saw the body again up to two weeks later. There were also pictures taken of this gentleman, and his picture became the screen-saver on the laptop belonging to one of our more motivated Marines.

The larger point that I’d like to touch on is that these are the consequences for sending young men and women into battle. These are the things that happen. And what I’d like to ask anyone who’s viewing this testimony is to imagine your loved ones put in such positions. Your brothers, your sisters, your nieces, your nephews, your aunts, and your uncles, and more importantly, and maybe most importantly, to be able to put ourselves in the Iraqis’ shoes who encountered these events every day and for the last five years.