Many respected scholars and human rights organizations have characterised Israel’s war in Gaza as a genocide. At the same time, other scholars and organizations have disputed this charge. Proving a charge of genocide is notoriously difficult, since it requires demonstrating not only that large numbers of civilians were killed but that they were killed intentionally with the aim of destroying their group “in whole or in part”.

A common misconception is that genocide must involve a very large number of deaths on the order of hundreds of thousands or millions. But this is false. The perpetrators of the Srebrenica massacre during the Bosnian War were found guilty of genocide despite the massacre’s death toll being less than 9,000. Hence the fact that “only” 70,000–100,000+ people have died in Gaza in no way refutes the charge of genocide.

Given the complexity of proving intent, establishing whether Israel has committed genocide is beyond the scope of this article. What the article argues instead is that two key features of the mortality data from Gaza are consistent with the charge of genocide.

The first such feature is the age and sex distribution of deaths. In a recent UN study, Colin Mathers and colleagues sought to characterise the patterns of age- and sex-specific mortality in various deadly events, such as genocides, violent conflicts and natural disasters. Comparing data from four genocides and a large number of violent conflicts, they found that the patterns of age- and sex-specific mortality were quite distinct.

In violent conflicts, mortality rates were substantially higher for men than for women, low for non-infant children and high for older age groups. In genocides, by contrast, mortality rates were only somewhat higher for men than for women and were much flatter with respect to age.

Two separate studies have compared the patterns of age- and sex-specific mortality from the early months of the Gaza War to the patterns documented in the UN study. Both found that the patterns from Gaza were a closer match to genocides than to violent conflicts — driven by unusually high mortality among women and children.

As Benjamin-Samuel Schlüter and colleagues note:

The mortality from the current war in Gaza does not exhibit strong differences between males and females, distinguishing it from the conflict schedule… The age pattern associated with genocide is the closest to the observed death rates due to the war, especially below the age of 40 years.

Or as Ana Gómez-Ugarte and colleagues note:

If the appropriate type of crisis is selected, the estimates can be very close to the true ones, as shown by our results when using the genocide pattern.

The data these authors analyzed come from the Gaza Health Ministry, which has been accused of inflating the number of deaths for political purposes. However, several studies have looked into this claim and concluded that the Health Ministry’s tally is probably an under-count.

Michel Guillot and colleagues cross-checked the Health Ministry’s data against the UNRWA’s register of refugees living in Gaza. Out of 34,344 individuals included in the data with complete identifying information, 64% also appeared on the UNRWA’s refugee register — which is almost identical to the 66% of the population known to comprise refugees. This makes it unlikely that a large number of the names were simply fabricated.

Matthew Cockerill and colleagues examined 1,079 child deaths that were abruptly removed from the Health Ministry’s data in March of 2025. They were able to verify that at least 61% did in fact occur and, of those for which a cause of death could be identified, 97% involved violence. They also determined that only 3% represented duplications, misidentifications or individuals later discovered alive. The reason the deaths were removed is that the Health Ministry only counts a death if an official has personally seen the body or a judicial ruling has confirmed it.

In addition, an investigation by the Guardian, +972 Magazine, and Local Call uncovered an internal IDF database that contained 8,900 deceased Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad fighters up to May of 2025. Since the Gaza Health Ministry’s death toll at the time was around 53,000, the investigation determined that at least 83% of those killed in Gaza were civilians. This figure is similar to Cockerill’s own back-of-the-envelope estimates based on the assumption that men are over-represented in civilian deaths by 32–50%.

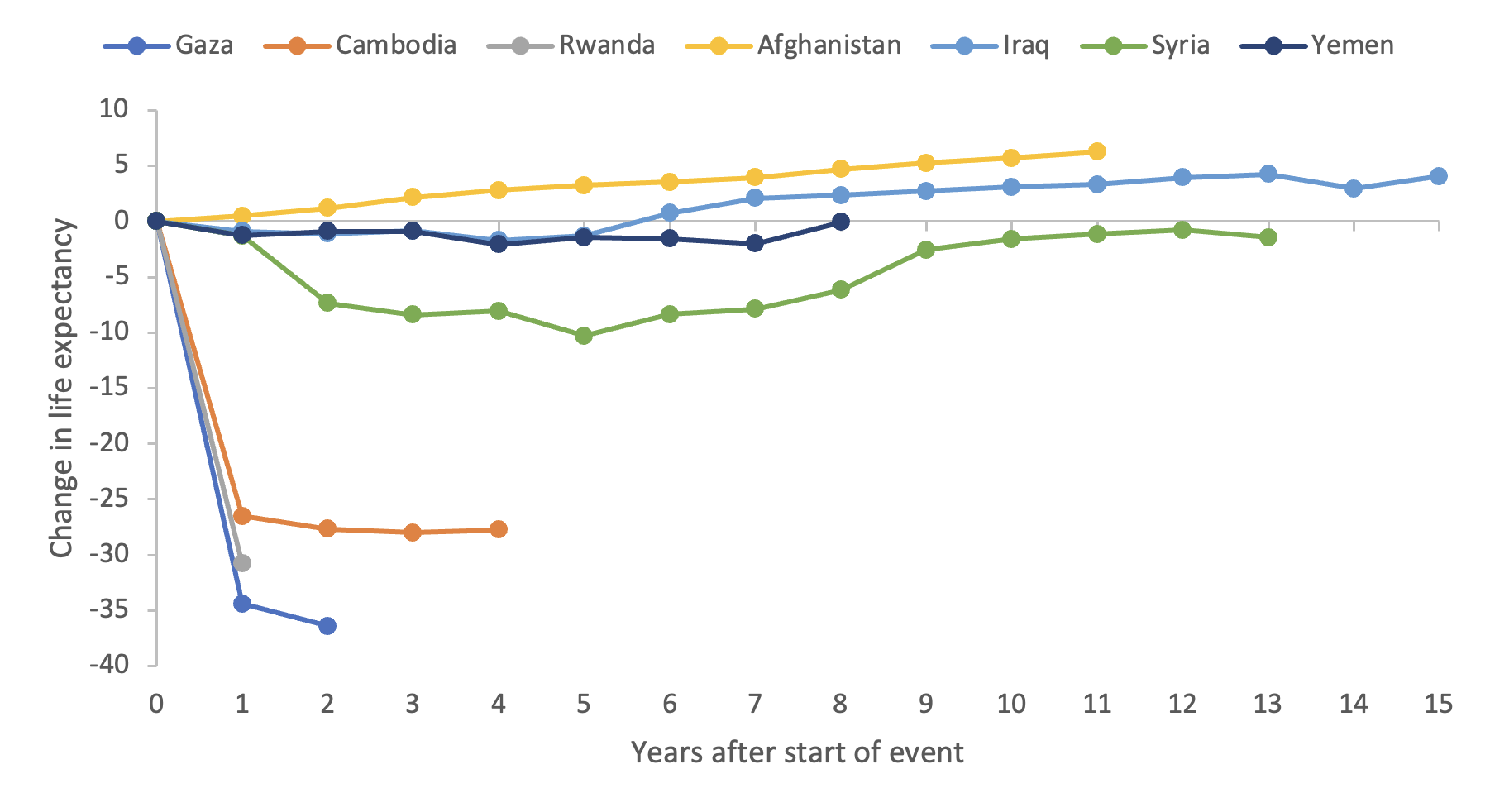

The second feature of the mortality data from Gaza that is consistent with the charge of genocide is the trajectory of life expectancy. Guillot and colleagues calculated that life expectancy in Gaza fell by 34.9 years in the period October 2023–September 2024. Gómez-Ugarte and colleagues reported an even greater loss for this period when adjusting for under-reporting of deaths. They also reported losses of 34.4 years 36.4 years for the calendar years 2023 and 2024, respectively.

This would mean that Gaza saw a huge cumulative loss across only two years of conflict. Such a sudden and dramatic fall in life expectancy did not occur during any of the recent wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria or Yemen. However, it did occur during the Rwandan and Cambodian genocides. This is shown in the chart below, using figures from Gómez-Ugarte and colleagues and Our World in Data.

There is still some uncertainty surrounding the estimates for Gaza, but the overall trajectory is not in dispute. The fall in Rwanda would be even more dramatic if figures were available for Tutsi specifically, though it is worth noting that thousands of Twa and Hutu “traitors” were also killed.

Is the Gaza War a genocide? Two key features of the mortality data are consistent with that charge: first, unusually high mortality among women and children; second, the sudden and dramatic fall in life expectancy. In these respects, the war resembles the Rwandan and Cambodian genocides more closely than any other recent conflict involving the US or Israel.

Noah Carl is Editor at Aporia Magazine. You can follow him on Twitter @NoahCarl90.