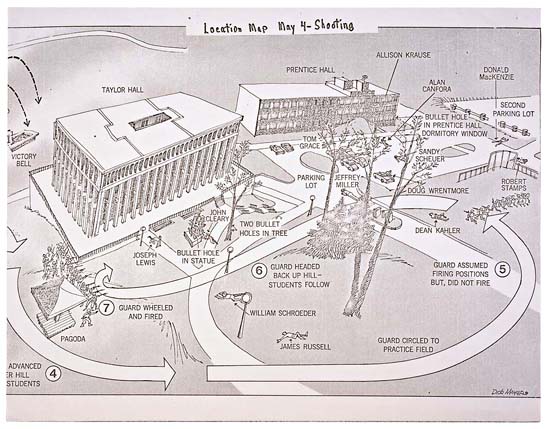

Location Map of the Kent State shootings from The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest

On two days in May fifty years ago, American police and National Guard troops fired their weapons into crowds of anti-Vietnam-War protesters, killing six American students at two American state universities.

On May 4, 1970 Ohio National Guard troops fatally wounded Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer, and William Schroeder at Kent State University.

On May 15, officers of the Jackson, Mississippi Police Department and the Mississippi Highway Patrol killed Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green at historically black Jackson State.

The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest appointed by Richard Nixon to investigate the incidents concluded that “the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of [Kent State] students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable” and that “the 28-second barrage of lethal gunfire [at Jackson State] was completely unwarranted and unjustified.”

In laying the theory for the modern nation-state as a bulwark against civil disorder, Thomas Hobbes insisted that its subjects retained “the liberty to disobey” orders “not to resist those that assault” them.

Yet while the 1970s would bring reductions in state power, with the cessation of the Vietnam War and its associated draft, such a right was never conceded in principle; the Commission recommended that “possession or use of weapons on campus by students should be strongly condemned” with no exceptions for self-defense. What the Commission called “the confidence of white officers that if they fire weapons during a black campus disturbance they will face neither stern departmental discipline nor criminal prosecution or conviction” was borne out.

While the Commission noted the discontent of those in higher education who “seek a community of companions and scholars, but find an impersonal multiversity,” it recommended increasing the role of state funding, which would effectively shift the leverage of power further away from the participants. As David Friedman noted at the time, “the lack of student power which the New Left deplores is a direct result of the success of one of the pet schemes of the old left, heavily subsidized schooling.”

The events of half a century ago serve as a reminder, as Voltairine de Cleyre observed a full century ago, that “the basis of all political action is coercion; even when the State does good things, it finally rests on a club, a gun, or a prison, for its power to carry them through.” Remembering our unvarnished history can revive such candor long before 2070.

New Yorker Joel Schlosberg is a contributing editor at The William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism. This article is reprinted with permission from William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism.