An unprovoked invasion by one of the world’s largest militaries, armed with a feared arsenal of weapons of mass destruction. Quasi-universal condemnation of the offending state. The international community in disarray over how to respond. I’m not referring to Russia’s attack on Ukraine in February 2022, but Iraq’s of Kuwait in August 1990. Yet one could be forgiven for readily conflating the two, given that the same set of circumstances and contradictions in place now were the very same that existed then.

The reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has gone in a predictable direction, led primarily by the United States and its allies. President Biden released an official statement condemning the “unprovoked and unjustified attack by Russian military forces.” Several days later, US Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield reiterated this sentiment, going even further by promising that Russians will “feel the pain” of sanctions imposed by the United States and its allies until Russian forces are withdrawn from Ukraine. Unlike Kuwaitis in 1991, however, Ukrainians have little reason to expect a direct American military confrontation with Russia on their behalf, given its long-distance nuclear weapons capabilities, that, contrary to some speculation, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq simply did not possess.

For the time being, Ukrainians can only hope that the current package of diplomatic pressure, economic sanctions, and armament support from the US and NATO-aligned countries will be enough to beat back the Russian invasion. But sans a direct confrontation with Russia, has the United States really exhausted all of its nonviolent options in its support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity? To the contrary, there is good reason to consider that the United States’ failure to address the very same sins that it has (rightly) condemned Russia for in the foreign policy of its allies and itself has actively brought us to the edge of the nuclear precipice, when a simple, peaceful, lawful, and above all moral alternative is readily available.

Condemning Aggression in Ukraine, But Endorsing It in Palestine (and Yemen, and Syria, and Western Sahara, and…)

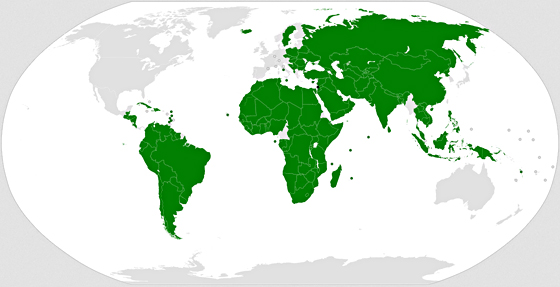

Like Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was condemned by the United Nations. However, while the resolution condemning Iraq in 1990 was drafted and approved by the United Nations Security Council, the resolution on Russia’s invasion was instead made by the United Nations General Assembly due to a Russian veto, whose resolutions are generally not legally binding compared to those of the UNSC. While the majority of votes condemned Russia, there were several notable and significant exceptions, such as major Russian economic and security partners China and India, whom abstained.

Given that China, India, and South Africa,1 which likewise abstained from condemning Russia’s invasion, combined accounted for nearly a quarter and more than fifteen percent of total import and export trade with Russia in 2019, respectively, it is unlikely that a condemnation from such partners would go unnoticed by Russian policymakers. Indeed, since the invasion India has committed to buying millions of barrels of Russian oil otherwise sanctioned by the US and NATO-aligned states, with China expected to follow suit. To further illustrate the full extent of Russia’s economic ties with some of these countries, it is estimated that China alone accounts for more than one tenth of all Russian foreign currency reserves.

What might explain the disparate reactions to such a blatant violation of international law? One understudied explanation is that the United States, which has taken up the premier role of opposing Putin’s “aggressive” behavior, has funded or otherwise supported comparable disregard for international law among its own allies and partners elsewhere. This includes the time prior to and continuing through the Biden Administration, the most notorious example of which has occurred with respect to the State of Israel. Since 1967, Israel has occupied the Palestinian territories of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip,2 as well as the Syrian territory of the Golan Heights. The Israeli government has annexed several of these territories and resettled them with its own civilian population, both violations of customary international law.

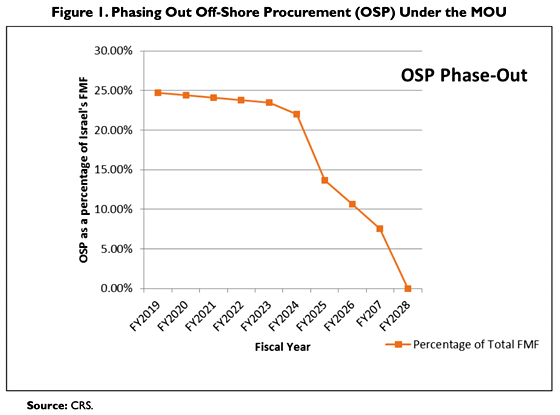

Concurrently, according to the Congressional Research Service, the United States has provided Israel with more than $100 billion in military aid since 1948, with $3.8 billion spent in 2021 alone. This could include an additional proposed $1 billion in funds for the Iron Dome missile defense system, bringing the projected spending on military aid for Israel for the following year to a total of $4.8 billion, which in past years has accounted for the most military aid given to any country in the entire world, and the second most for all categories of US foreign aid. But not only is Israel given state-of-the-art American aircraft and munitions free of charge under current agreements, but it is also permitted to spend up to a quarter of the aid on its own defense industry until Fiscal Year 2028 as part of the Off-Shore Procurement program.

Despite the largesse military of hardware given to Israel by the United States, essentially none of it has been leveraged to curb Israel’s violation of international law. With President Biden on record stating that he is steadfastly opposed to withholding aid until Israel obeys international law, and his Secretary of State’s Antony Blinken refusal to reverse the previous administration’s legitimization of the Israeli annexation of East Jerusalem (and maintaining the same of the occupied Golan Heights), the Administration’s repeated condemnations of the Russian invasion and occupation of Ukraine and talk of a “rules-based international order” ring hollow.

Supporters of the Israeli position argue that the situations of Palestine and Ukraine are nothing alike, purportedly because Palestinians stubbornly reject Israel’s existence, and hence Israel cannot withdraw from the Palestinian territories without risking its own national security. This is rubbish, as in 1988 the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the “sole and legitimate representative of the Palestinian people”, committed to a two-state solution with Israel in a communiqué to the Palestinian Declaration of Independence, and in 1993 formally recognized the State of Israel. Subsequently, the PLO has come out in support of the Arab Peace Initiative, which would normalize the Arab League’s relations with Israel in exchange for the establishment of a Palestinian state in the territories occupied in 1967, as well as a solution to the issue of Palestinian refugees that would take into account Israel’s demographic concerns (more on this here). Even the more hardline Hamas faction, which governs the Gaza Strip and in recent years has been Israel’s foremost adversary, has expressed a willingness to endorse the Initiative.

Similarly, a supporter of Israel could approve of the continued occupation/annexation of the Golan Heights on the basis that Syria has never recognized Israel, and the two technically remain in a state of war. Yet this completely ignores that according to former US President Bill Clinton, as early as the 1990s the Syrian government has been willing to recognize Israel in exchange for the return of the Golan Heights to Syria.3 This was attested to by the fact that Syria, by virtue of its membership in the Arab League and Organization of Islamic Cooperation, has endorsed the Arab Peace Initiative (which includes the cession of the Golan Heights to Syria) since 2002 and 2006, respectively. One could argue that due to Syria’s ongoing civil war, a return of the Golan Heights at present is not feasible, but this does not explain for why approximately a decade Israel did not act on Syria’s offer. In fact, when it comes to Israel’s policy of occupation, blockade, and settlement, the thoughts of Yair Lapid, scheduled to become Prime Minister of Israel next year, offer a better explanation than the safety of Israeli citizens: “maximum Jews on maximum land with maximum security and with minimum Palestinians”. In other words, a justification scarcely different than some of those that have been offered by Putin for meddling in Ukraine.

For what it’s worth, the majority of UN member-states recognize the State of Palestine within the borders prescribed by the Arab Peace Initiative, including the aforementioned countries that refused to take a public stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This does not, curiously, include the United States, which has at times even refused to recognize the territories as occupied Palestine, in spite of being represented by an authority that has recognized Israel for decades and has publicly committed to a peace agreement that would uphold Israel’s status as a Jewish-majority electorate. This is not a new phenomenon, as even in 1990 Saddam Hussein used this double standard to legitimize his very own occupation and annexation of Kuwait. The contradiction in terms is recognized by the Palestinians themselves, a majority of whom in a recent poll indicated that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent reactions have highlighted American hypocrisy towards the two conflicts. The US may not be able to do much else in the way of halting Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, but it at the very least could not subsidize Israel’s in Palestine and Syria.

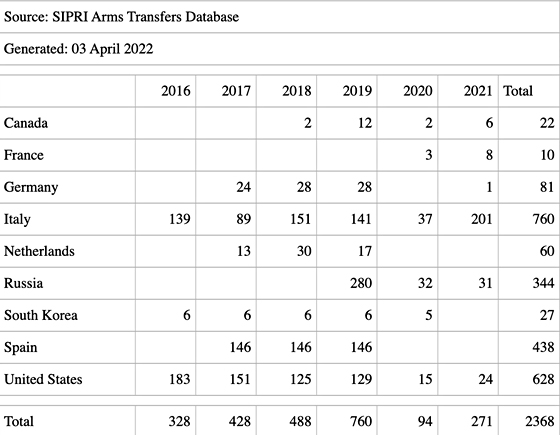

Israel is far from alone among American allies in flaunting the norms of international relations and being rewarded for it, however. NATO member Turkey, which the United States has a treaty obligation to defend were it to come under external attack, has occupied the Northern half of Cyprus since 1974, where it has set up a puppet state that is unrecognized by every country on the planet except for Turkey itself. Since then, it has ethnically cleansed more than 100,000 Greek Cypriots and prevented them and their descendants from returning to their homes, as well as transferring its own citizens into the occupied territory. More recently, beginning in 2016 Turkey has directly intervened in the Syrian Civil War by committing thousands of soldiers on the ground and backing Syrian opposition groups, ostensibly for the purposes of combating the Islamic State but in reality to also put down Kurdish militants based in the country as well as carve out its own sphere of influence among the various parties involved in the conflict. Throughout all of this however, the United States has continued to support Turkey in spite of behavior that it would have otherwise condemned with Russia or other adversaries, delivering 628 million trend-indicator worth of heavy weaponry per the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, or SIPRI, between 2016 and 2021, more than a quarter of all deliveries in this period, including at least $33,689,676 in security assistance.

Arms transfers from selected states to the Republic of Turkey, 2016-2021. For

methods of calculation, see SIPRI’s webpage.

Additionally, according to the Defense Manpower Data Center, as of December 31, 2021 Turkey is protected by nearly 1,800 known active-duty US military personnel stationed across the country at least thirteen sites, whom are expected to defend a government with their lives engaged in behavior that their own superiors repudiate elsewhere. Clearly something is off in the rules-based international order.

Morocco has also been occupying its neighbor Western Sahara for decades, which until 2020 was not recognized as part of Morocco by any country with the exception of Morocco itself. But in 2020 the United States decided to extend recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, reportedly in exchange for Moroccan normalization with Israel. Since then, Morocco has received $20 million in military credits from the US’s Foreign Military Financing program, which according to SIPRI were used purchase weaponry such as M-1A1 Abrams tanks, Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, and TOW missiles.4

The Biden Administration has continued to view Western Sahara as part of Morocco, though to its credit has introduced some restrictions on military aid. Meanwhile, throughout May of 2018 the United Arab Emirates, another heavy recipient of American arms sales per SIPRI’s database,5 staged a takeover of Socotra. The island, recognized as belonging to Yemen and known for its unique biodiversity, found itself under Emirati governance, with the nation’s flags adorning government buildings. The unspoken annexation was condemned by the internationally recognized Yemeni government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, itself the UAE’s ally in Yemen’s now-seven year civil war.

While Saudi Arabia ended up negotiating a nominal return of Socotra to Yemeni sovereignty, the island remains under the de facto control of the Southern Transitional Council, a UAE-backed separatist militia, and continues to rule Soqotris by proxy. The United States’s policy during this time has been to continue to seek armaments for the UAE despite Abu Dhabi’s attempts to dismember its own ally’s territorial integrity, hesitating only due to public outcry over the UAE’s conduct in the civil war. Furthermore, a 2019 investigation by CNN found that U.S.-origin MRAP military vehicles had been transferred to these very same illicit separatists by the UAE. While the Department of Defense denies that Washington had authorized the transfer of such equipment, the fact that the US still pursues arm sales to the UAE demonstrates that at the very least American policymakers are willing to turn a blind eye to the state sponsorship of armed separatists so long as an allied state does it, exactly what Putin had been guilty of in Eastern Ukraine over the past eight years prior to his invasion.

If a country like Ukraine is seeking to uphold the norms of international relations, it’s unlikely to find any help in the United States at present. One can only wonder of the effects the US’s positions must have on other, similarly situated world powers.

Learning From the Best

How can the United States expect its allies, much less its adversaries, to adhere to lawful conduct in its foreign policy when it fails to do so in its very own? Without delving too deep into the historical record of US transgressions, it will suffice to observe its ongoing violations of international law, or at the very least highly questionable actions that the US would be quick to chastise elsewhere, to make apparent that any talk of a rules-based international order by the United States is at best an opportunistic gesture towards humanitarianism devoid of any genuine commitment on its own part.

In February 2021 the United States conducted airstrikes in Syria in response to attacks on US personnel in Iraq allegedly carried out by Iran-backed militants. With no United Nations Security Council authorization, a dubious claim of self-defense, and without permission from the Syrian government, this incident can credibly be considered an act of aggression against the Syrian Arab Republic. The following June President Biden again ordered airstrikes against Iran-backed militants, this time in Syria as well as Iraq, for the same reasons as before. While US forces are stationed in Iraq in partnership with the Iraqi government to combat the Islamic State, apparently the strike in Iraq was committed without the authorization of Iraq itself, with its Prime Minister going as far as hounding the United States for its “blatant and unacceptable violation of Iraqi sovereignty and Iraqi national security”. I’ll let the reader be the judge of that one.

It’s arguable whether or not there should even be a US military presence in Iraq in the first place, given that in January 2020 Iraqi parliamentarians representing a majority of the country’s electorate voted to urge the government to expel US troops from the country. At that point, then-President Donald Trump threatened to sanction Iraq were this request to be carried out. Though Iraq still technically permits US troops to be stationed in the country in order fight the Islamic State, it is highly questionable of what utility this is, given that Iraq had declared that group had been “evicted” from the country back in December of 2017. More likely, the United States remains as a means of blunting its competitor Iran’s influence in the region.

A similar dynamic plays out in Cuba, where the US maintains a military base and prison camp for “unlawful combatants” at Guantanamo Bay. The Cuban government from Fidel Castro onward has demanded the return of this territory to Cuban sovereignty, but the United States justifies its retention of the area based on a 1934 treaty between the two states that allows the US to lease the property as a naval station so long as it pays annual rent to the Cuba government. But Cuba has not intentionally cashed the rent payment since the previous regime, and the treaty itself spells out that US forces cannot be withdrawn unless the United States unilaterally or both countries jointly decide to do so. In other words, Cuba has no say of its own over this part of its own country. This arrangement, and that governing the stationing of US forces in Iraq, are eerily similar to the one-sided agreements that Russia has strong-armed Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine into signing in order to maintain an indefinite Russian military presence there, even though the presence itself is not supported by the governments of the respective countries, similar to the US presence in Cuba and Iraq.

If US involvement in Iraq and Cuba is sustained by a thin veneer of legal casuistry, then the US occupation of Syria is blatantly incompatible with international law. It is estimated that as of this year the United States currently has about 1,000 active-duty military personnel and armed contractors located in Syria, not a single one of which has been agreed to by the internationally-recognized Syrian government, for the same discredited stated purpose as in Iraq. Along with the occasional air raid, there is no indication that the US campaign in Syria will be coming to an end any time soon. Even more egregious, the United States still prohibits the Chagossian people from returning to their homes on the Chagos Islands, whom were expelled by the United Kingdom several decades ago in order for the United States to construct an airbase there. Even after an International Court of Justice advisory opinion in 2019 ruled that the U.K. and US relinquish control of the islands and provide the Chagossians with a right of return and additional compensation, both countries have yet to honor this judgment and continue with their violation of international law. An analogous injustice has occurred in the Russian-occupied territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia, where hundreds of thousands of ethnic Georgians have similarly been expelled by Russian-backed forces. Just as the USrejected the global plea to allow the Chagossians to return to their homes, Russia did the same with Georgians and theirs.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that the United States has squandered any moral authority it may have otherwise had in getting the world to unite behind its opposition towards Vladimir Putin’s monstrous attack on Ukraine, through support for its allies’ own illegal actions as well as its very own. This is reflected in the composition of states who decided to condemn Russia’s actions and those that decided to remain silent, among the latter several world and regional powers with an ambiguous relationship to Washington.

I obviously cannot say for sure what kind of effect an American foreign policy with integrity could have on Putin’s decision-making nor that of the states of that have tacitly backed him. Perhaps everything would have played out exactly the same regardless. But there is nothing to lose in upholding the self-determination of all peoples as an intrinsic moral good that might also serve as an asset for US foreign policy. One can optimistically imagine what impact a diplomatic grand alliance of the US and nonaligned states such as India, China, Pakistan, South Africa, and even Iran might have on bringing Putin to heel if the US were to commit to upholding international law in word as well as in deed. But until then, one-sided American policy that arbitrarily raises up allies and strikes down enemies regardless of their commitment to a rules-based international order, hinged on mutually-assured destruction, will unfortunately have to suffice.

1 Another member of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) emerging economies forum. Brazil was the only member-state that condemned the invasion.

2 In 2005 Israel removed all settlements from the Gaza Strip, but continues to occupy a several-hundred feet-wide strip of land within the territory as a militarized buffer zone as well as controlling all movement in and out of Gaza through a land, air, sea blockade.

3 Clinton, Bill. My Life. Knopf Publishing Group, 2004. pp. 886-887.

4 To view SIPRI’s data, visit https://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/page/trade_register.php, select the United States as a supplier and Morocco as a recipient, and enter the desired years.

5 To view SIPRI’s data, visit https://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/page/values.php and enter the importer country with the desired years.

Thomas Resnick is a freelance writer on foreign policy among other political and cultural issues, as well as in the process of founding a Jewish organization to oppose military action against Iran. You can subscribe to his newsletter at https://thomasresnick.substack.com/.