Given my Judeo-Christian roots, I’ve long wanted to visit “The Holy Land.” The U.S.-supported Israeli attack on Gaza this past winter lent urgency to that longing. In mid-May I joined a delegation going to Israel and the West Bank of the Israeli-Occupied Palestinian Territories. Altogether I spent a month experiencing those tense and militarized lands.

What most surprised me on this tour was how at home I felt – not in the West Bank, but in Israel. Except for signs in Hebrew, things often seemed so “American” that it was like we were in the 51st state. For example, even in the Arab quarters of Israeli cities, many non-Arab Israelis dress with an immodesty (pleasing to my male, Western eye) that surely offends the indigenous Muslim people they live among.

But this at-home feeling went beyond appearances. It was in the attitudes. The non-activist Israelis I met reminded me of many folks back in the U.S. Here were nice, hospitable, English-speaking people who – just as in the U.S. – live in what I call the “Bubble.” Colonizing and nationalizing our minds, the Bubble is spun by our governments and mainstream media. It narrows our horizons, drowns our dissent, stifles the voices of the voiceless. Distracting and trivializing, the Bubble shelters us from others’ pain.

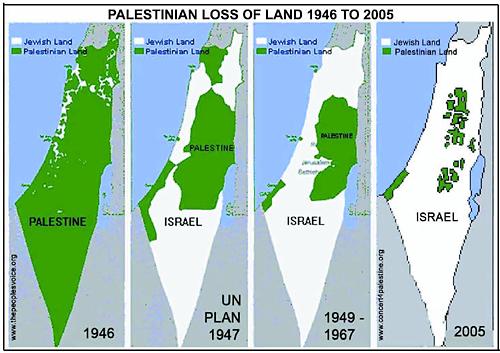

The non-activist Jewish Israelis I met seemed oblivious to – or were quick to rationalize – how predatory their military and the Israeli settlers they protect were being in the Occupied Territories. They took for granted the great theft of indigenous Palestinian land supported with their taxes (and with $3 billion a year of our taxes). After centuries of inhabiting what has become Israel proper, in recent decades Palestinians have been either pushed into exile or relegated by force to the caged reservations and “Bantustans” of Gaza and the West Bank. Israeli scholar Ilan Pappé calls this historical process “ethnic cleansing.”

The fear that some Israelis feel regarding Palestinians mirrors the fear some U.S. whites feel toward people of color. These Israelis also were quick to blame the victim and to shudder at the “other.”

My sense is that these good people had little idea how Israel was economically strangling Palestine. Or that the (much publicized) Palestinian terrorism perpetrated on Israelis was a fraction of the (inadequately publicized) episodic terrorism of the Israeli air force and the daily, systemic violence that the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) perpetrates on Palestinians. (One Jewish Israeli woman referred to the protracted aerial bombing of Gaza, which killed 900 civilians, as an “incident.”)

Those Other Settler States

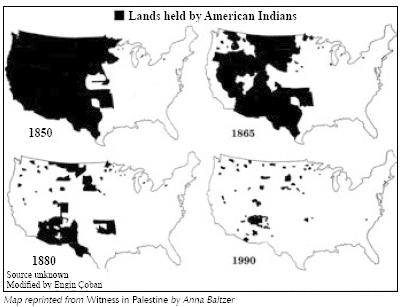

I was prepared for what I saw in Israel/Palestine thanks to my knowledge of what European settlers did to First Nations people in what became the United States. The five or six weeks I spent back in the early Eighties in South Africa were also good preparation. There too I was struck by how at home I felt. White South Africa was also a 51st state – one then backed by the U.S. government.

In Johannesburg, the commercial and government center, many of the affluent white minority lived in gated communities while by law blacks lived in the grim, sprawling Soweto ghetto – whose few roads in and out were controlled by the South African Defense Force.

The South Africa I experienced was legally and physically divided by ethnicity and skin color. “Divided,” though, doesn’t begin to acknowledge the stark disparity of wealth, power, and opportunity.

In Israel – and in the U.S. – there are similar disparities, the product of similar apartheids. (Another thing that surprised me, in both Israel and Palestine, were the legions of young male and female Israeli soldiers… many casually toting automatic weapons.)

The U.S., South Africa, Israel: all three are/were expansionist “settler states.” All three have been populated by land-hungry Judeo-Christian Europeans. These outlanders arrived with far more capital and political and military backing than the indigenous people whose land they coveted – and, by hook or by crook, eventually confiscated, or are now bent on confiscating.

Our delegation spent a week in the occupied West Bank. We passed through the Separation Wall, the Berlin-like barrier dividing Israel from its hapless – but stubborn and resisting – colony. The thing to note about the Wall, which is four times the height of a man, is that only 20 percent of it is built on the Green Line, the internationally recognized border between Israel and the Occupied Territories.

The Israelis built most of the Wall well inside the West Bank on inhabited or cultivated Palestinian land – thereby seizing more Palestinian territory. That land grab is part of achieving “facts on the ground” ASAP before some “peace process” forces the Israelis to stop multiplying their (illegal) settlements throughout the West Bank.

The Last Surprise… Sort Of

In the West Bank I was also surprised – or rather would have been if I hadn’t already read Anna Baltzer’s Witness in Palestine – by all the military roadblocks. As privileged foreigners, we were waved along by the Israeli soldiers. But these same soldiers might hold up Palestinians for hours at a time or delay market-bound Palestinian produce until it rots.

Like the Wall, most of the roadblocks aren’t at the Green Line; they are sprinkled all over the West Bank. They strangle Palestinian movement, both personal and commercial, within their own territory. They fragment the West Bank, undermining its commerce, leashing its people, and generating resentment.

The roadblocks seem intended to ratchet up daily misery. Maybe even more Palestinians will simply pack up and flee. The goal: to transform the West Bank (in the words of the old Zionist canard) into “a land without people for a people without land.”

One way I’ve come to visualize the occupation is to imagine the indigenous Onondaga Nation here in Onondaga County, N.Y., a nation that white settlers long ago reduced to a fraction of its former territory. But to make the situations more comparable, suppose a 25-foot wall separated the Onondagas from the surrounding white-controlled county. Imagine that the Onondagas risked being shot from sniper towers or detained for months without trial if they somehow passed through the wall without a permit. Imagine further that within the Onondaga Nation there were numerous militarized roadblocks cutting Onondagas off from their neighbors or their crops. Such a bizarre scenario would be a microcosm of the occupied West Bank.

During Ed’s first two weeks in Israel/Palestine, he traveled with a Christian Peacemaker Teams delegation. The dozen delegates met with Jewish, Christian, and Islamic peace and justice activists in Jerusalem and the West Bank (Bethlehem, Hebron, At-Tuwani). Then for two more weeks Ed toured Israel. The delegation did not visit Gaza, which is still blockaded by the Israeli military.

This piece originally appeared in the Peace Newsletter of the Syracuse Peace Council.